Healthcare providers and patients have traditionally thought The infections that patients get within the hospital are brought on by superbugs that they’re exposed to during their stay in a medical facility. The genetic data of the bacteria that cause these infections—think CSI—tells a unique story: Most health-related infections are brought on by previously harmless bacteria that patients already had on their bodies before they were admitted to the hospital.

Research compares bacteria within the microbiome—people who populate our noses, skin, and other areas of the body—with the bacteria that cause them lung infection, Diarrhea, Bloodstream infections And Surgical site infections shows that the bacteria that live harmlessly on our own bodies once we are healthy are most frequently accountable for these nasty infections once we are sick.

Our newly published research in Science Translational Medicine adds to the growing variety of studies supporting this concept. We show that many surgical site infections following spinal surgery are brought on by microbes already on the patient's skin.

Surgical infections are an ongoing problem

Among the varied kinds of healthcare-associated infections, postoperative wound infections stand out as particularly problematic. A 2013 study found that surgical site infections accounted for the biggest share of the annual cost of hospital-acquired infections overall over 33% of the $9.8 billion issued annually. Postoperative wound infections are also a very important cause Hospital readmission and death after the operation.

In our work as clinicians on the University of Washington Harborview Medical Center – yes, the one in Seattle “Grey’s Anatomy” is supposedly based on it – We have seen how hospitals operate extraordinary lengths to forestall these infections. These include sterilizing all surgical equipment, using ultraviolet light to wash the operating room, maintaining strict surgical gown protocols, and monitoring airflow within the operating room.

Morsa Images/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Nevertheless, postoperative wound infections occur after approx 1 in 30 procedures, normally without explanation. While rates of many other medical complications showed regular improvement over time, data from the Agency for Health Research and Quality and that Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the issue of postoperative wound infection is just not improving.

Since the administration of antibiotics during surgery is a cornerstone of infection prevention, the worldwide increase in Antibiotic resistance Infection rates are predicted to extend following surgery.

BYOB (Bring your personal bacteria)

As a team of doctors and scientists with expertise including Intensive care, Infectious diseases, Laboratory medicine, microbiology, Pharmacy, Orthopedics And NeurosurgeryWe wanted to raised understand how and why our patients developed surgical infections despite following really useful protocols to forestall them.

Previous studies of surgical site infections were limited to a single species of bacteria and used older genetic evaluation methods. But latest technologies have opened up the opportunity of studying every kind of bacteria while testing their antibiotic resistance genes.

We focused on infections in spine surgery for several reasons. First, similar numbers of men and women undergo spinal surgery for a wide range of reasons throughout their lives, meaning our findings can be applicable to a bigger group of individuals. Second: more Healthcare resources are spent on spine surgery than another kind of surgery within the United States. Third, infections can occur after spinal surgery particularly devastating for patients, as repeated surgeries and long courses of antibiotics are sometimes required to have a probability of recovery.

Over a period of 1 yr, we took samples of the bacteria living within the nose, skin and stool of over 200 patients before surgery. We then followed this group for 90 days to check these samples with subsequent infections.

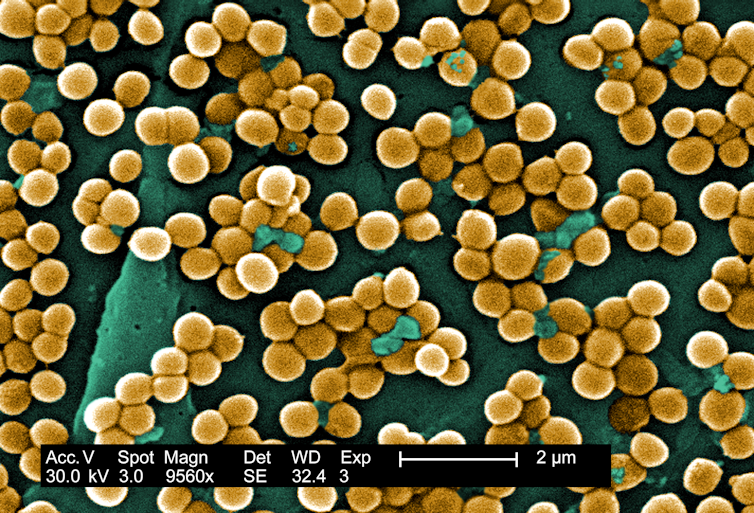

CDC/Janice Haney Carr/Jeff Hageman, MHS

Our results showed that although the kinds of bacteria that live to tell the tale the skin of the back of patients vary significantly from individual to individual, there are still some some clear patterns. Bacteria that colonize within the upper back area across the neck and shoulders are more just like those within the nose; those normally present within the lower back are more just like those within the intestines and stool. The relative frequency of their occurrence in these skin regions largely reflects how often they occur in infections following surgery on the identical specific regions of the spine.

Actually, 86% of bacteria Infections caused after spinal surgery were genetically adapted to bacteria that a patient carried before the operation. This number is remarkably close Estimates from previous studies using older genetic techniques focused on .

Almost 60% of infections were also proof against the prophylactic antibiotic administered during surgery, to the antiseptic used to wash the skin before incision, or to each. It turned out that the source of this antibiotic resistance was also not acquired within the hospital, but from microbes that the patient had already unknowingly lived with. They likely acquired these antibiotic-resistant microbes through previous antibiotic exposure, consumer products, or routine community contact.

Prevention of surgical infections

At first glance, our results seem intuitive – surgical wound infections are brought on by bacteria residing on this a part of the body. However, this finding has potentially serious implications for prevention and care.

If the almost certainly source of a surgical infection – the patient's microbiome – is understood upfront, this provides medical teams with the chance to guard against it before a planned procedure. Current infection prevention protocols, reminiscent of antibiotics or topical antiseptics, follow a uniform model – for instance, the antibiotic cefazolin is used for this Any patient undergoing most procedures – but personalization could make them simpler.

FG Trade/E+ via Getty Images

If you had major surgery today, nobody would know whether the realm where your incision can be made was colonized with bacteria that were proof against the usual antibiotic therapy for that procedure. In the long run, doctors could use details about your microbiome to pick out more targeted antimicrobials. However, further research is required on easy methods to interpret this information and to know whether such an approach would ultimately lead to raised results.

Today, Practice guidelines, commercial product developmenthospital Protocols And Accreditation In the context of infection prevention, the main focus is commonly on the sterility of the physical environment. The proven fact that most infections don’t actually originate within the hospital is probably going a testament to the effectiveness of those protocols. However, we consider that shifting to more patient-centered, individualized approaches to infection prevention has the potential to profit hospitals and patients alike.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply