My students are inclined to imagine the Middle Ages as something just like the video games Kingdom Come or Total War: an age of complete political chaos, where swords and daggers reigned, and masculinity and physical strength were more essential than governance.

As a historian of the Middle AgesI consider that this turbulent image has less to do with reality than with the Middle Ages – a term for the way modern people have reimagined life within the European Middle Ages, roughly between 400 and 1400.

Medieval Europe could have been violent, and its standards of governance wouldn’t receive praise today. But people were definitely in a position to recognize dysfunctional politics, whether within the royal court or within the church, and suggest solutions.

At a time of increasing authoritarianismand when U.S. politics appears to be in chaos, it's price looking back at how societies defined bad governance centuries ago.

Tyrants, kings and bad bishops

Authors within the Middle Ages considered politics when it comes to leadership and bad politics is sometimes called “tyranny.”“whether or not they were criticizing a frontrunner or a whole system. In any case, tyranny – or autocracy because it is commonly called today – is an idea that great thinkers have debated since precedent days.

For the traditional Greeks, tyranny meant ruling single-handedly for the good thing about a person. Aristotle, the elemental thinker on the topicdefined tyranny as the alternative of the right rule, which he believed to be kingship: a single ruler resolve in the overall interest of all. In his view, a tyrant was driven by the need for “power, pleasure and wealth,” while a king was driven by honor.

Modern political theorist Roger Boesche observed that tyrants are inclined to reduce the free time of the population. According to Aristotle, free time enabled people to think and “do” politics – that’s, to be residents.

During the Roman Republic, political thinkers compared tyranny to a diseased limb that needed to be cut off from the body politic. Ironic, certain Romans eliminated Julius Caesar fearing he would turn into a tyrant – only to get Augustus, who eventually became emperor.

Types of despots

In late antiquity, political writers also began to take into consideration tyranny in religious leadership.

Einsiedeln Monastery/Wikimedia Commons

In these “sentences“, a series of theological books, the seventh-century Archbishop Isidore of Seville addressed the issue of bad bishops. These men behaved like “proud pastors,” he wrote, who “tyrannically oppress the common people, don’t lead them, and demand from their subjects not the respect of God, but their very own.” In general, Isidore criticized the political incompetence that existed on the anger, pride, cruelty and greed of the leader.

Centuries later, European leaders and writers were still debating the character of tyranny—and what to do about it.

John of Salisbury, a bishop and philosopher in Twelfth-century England, proposed a reasonably radical solution: tyranny. In “Policraticus,” writings on political theory, he wrote that it was an obligation to revive the order of things kill a tyrant who was evil, violent and oppressive.

However, in John's organic conception of tyranny, a tyrant (the body) could only exist with the support of society (its limbs). He was certainly one of the earliest authors to argue that tyranny survived not simply on the whim of the tyrant, but with the support of his followers.

In the 14th century, the leading legal thinker of the time, Bartolus de Sassoferrato, A distinction is made between two types of tyranny. Despots got here to power through legal means, but acted illegally. He defined usurpersHowever, as rulers who seized power unlawfully, they indulged in pride and disobeyed the law.

Defeat a tyrant

Sometimes unpopular or “inconvenient” leaders were canceledreminiscent of England's Richard II Transcript of his statement listed nearly three dozen charges against the dethroned king: from rejecting council, failing to pay loans and admonishing religious authorities to murder, disinheritance and accusing rivals. We know his end didn’t end well: he died while in captivity in 1400, but exactly how is a mystery.

In Germany, King Wenceslaus of the House of Luxembourg was deposed on August 20, 1400 on the grounds that he was a “useless, slothful, careless divider and unworthy owner of the empire”. The German newspaper Die Welt classifies him as the worst king in Germany – loves alcohol and his hunting dogs and is obsessive about temper tantrums.

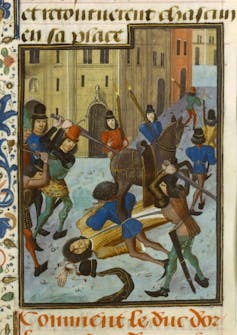

National Library of France/Wikimedia Commons

The violent removal of supposed “tyrants” didn’t all the time happen in secret. In 1407, Louis of Orléans, brother of the French King Charles VI, unwittingly fell right into a deadly trap. He was attacked by a big group of men who escaped and chased away onlookers.

In addition to being the brother of Charles “the Mad,” Louis was also a political rival to John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, with each men vying for control through the king's mental illnesses. John assumed responsibility for ordering the murder.

He and the lawyer he hired, a theologian named Jean Petit, argued that Burgundy had acted within the nation's interest order the death of a treacherous and greedy tyrantand that Ludwig's killing was due to this fact justified.

Men of material

Medieval politics didn’t make much distinction between the secular and non secular worlds. Popes were political leaders and may be viewed as tyrants.

While the Great Western Schism From 1378 to 1417, a split within the Catholic Church as multiple popes competed for the throne, all parties insulted one another with claims of illegitimacy and usurpation.

Enemies of Pope Urban VI for instance, argued that a telltale sign of tyranny was his uncontrollable anger, which disqualified him from leadership. Dietrich von Nieheim, who worked within the papal chancellery, noted in his chronicle: “The more he talked, the angrier Lord Urban becameand his face finally became like a burning lamp or a fiery flame with anger, and his throat was stuffed with hoarseness.” French cardinals deposed Urban in 1378 for illegitimacy and tyranny.

National Library of France/Wikimedia Commons

He was not the one pope deposed for his tyranny, although that word was not used. The Council of Constance, a council of European clergy convened to finish the schism, appointed Pope John XXIII. 1415 for reasons starting from disobedience and corruption to poor administration, dishonesty and stubbornness. Two years later, same advice put Pope Benedict XIII. awayaccused him of persecution, disturbing the peace, promoting division, promoting scandals and divisions, and being unworthy.

Medieval bishops and kings are hardly role models for democracies today, but their political world was not as chaotic as we frequently imagine. Even a world blind to democracy tried to define what bad leadership was and placed limits on the authority of those they deemed irresponsible. Rules for appropriate political behavior were established, although the law didn’t all the time prevail over violence.

But it's price remembering how people viewed bad leadership a whole lot of years before the political divide of our time. Today, nonetheless, now we have a significant advantage: we elect our leaders forwards and backwards.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply