The Jewish holiday cycle is largely an exploration and remembrance of the experience of exile. The fall festival of Sukkot, for instance, is well known in small huts, makeshift shelters that recall the Israelites' experience wandering in tents within the desert for 40 years after escaping slavery in Egypt. The story of Purim, a spring festival, takes place when ancient Jews lived in exile within the Persian Empire – and illustrates the uncertainty of life as a minority.

And then there may be Passover, which begins on April 22, 2024. It marks the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt – step one toward redemption. The theme of freedom dominates the vacation.

Passover is the one holiday that marks the transition from exile to wandering quite than homecoming, highlighting the complexity of exile – the main focus of my recently published book“Exile and the Jews,” co-editor of Marc Saperstein.

As a literary scholarI search for examples in novels and memoirs that illustrate exile and its consequences from different perspectives. Here I deal with those from the Jewish communities in Egypt and Iraq, the sites of the 2 largest exiles in Jewish history.

Into the unknown

In her 1983 novella “The miracle hater“The late Israeli writer Shulamit Hareven depicts the Hebrews on their way out of Egypt and their first taste of freedom. She writes a modern “midrash” – a rabbinic genre that develops a biblical text – and reinterprets it the story of Exodus.

While the biblical description focuses on heroic leaders like Moses and Joshua, Hareven focuses on the nameless masses: the Jewish slaves who’ve just crossed the Red Sea and are actually faced with life within the desert and must form a brand new community.

Tate Britain/Wikimedia Commons

Hareven's narrative delves deeper into the uprooting attributable to the exodus and explores the unexpected ambivalence with which the Hebrews face their newfound freedom. They have fled oppression, but meaning they have to leave behind all the things familiar to wander seemingly endlessly in the nice unknown of the desert.

Israeli author Orly Castel-Bloom weaves family history, history and a few alternative history into “An Egyptian novel“, published in 2015. It concurrently invents and lays claim to the one family that didn’t join the Exodus in precedent days, but remained in Egypt throughout the centuries. Although they’re only mentioned in passing, their existence makes the reader ponder whether any of the Hebrews actually remained behind.

Many Jews remained behind after the subsequent great exile in Jewish history began when Babylonia besieged Jerusalem and deported residents of the conquered city in 586 BC. When the Persian King Cyrus the Great issued an edict inviting the Jews almost 50 years later to return to Jerusalem and within the land of Judah only a minority did so. Those who remained in Babylon became the roots of the Diaspora and founded the oldest continuous Jewish community on the earth.

“Get out of Egypt”

More recently, Jews lived in each places of ancient exile: modern-day Egypt and Iraq. While those in Iraq could claim a centuries-old historyIt is more likely that the inhabitants of Egypt moved there in recent generations.

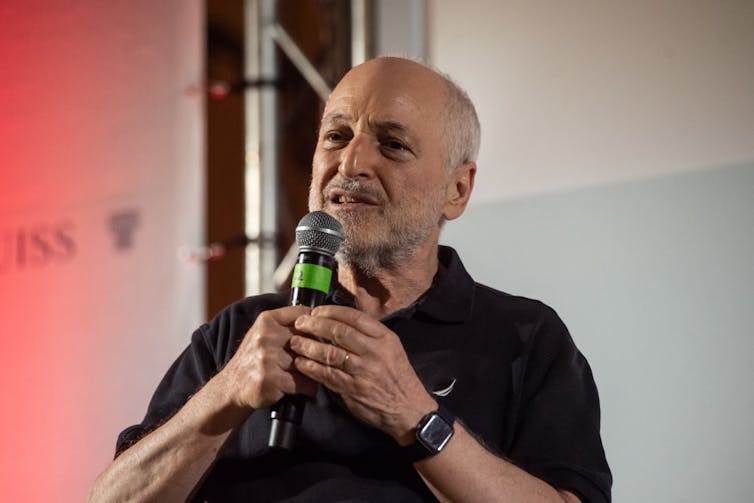

In his 1995 memoir “Out of Egypt“The novelist, essayist and professor André Aciman – best known for the filmed book “Call Me By My Name” – writes movingly and memorably about life on the eve of exile.

In the early Nineteen Sixties, Jews felt less welcome in Egypt. Aciman details the harassment his family had previously endured – anonymous phone calls, surveillance, government seizure of the family business Order given to depart.

“It never occurred to us that a Seder in Egypt would be a contradiction in terms,” he wrote within the New York Times, through which he described the Passover meal his family held the night before they left. The story of the Egypt of Exodus seemed far faraway from the Egypt of Aciman's childhood, the Egypt he loved.

Ivan Romano/Getty Images

When the author looked back on the last meal, he wondered exactly what was celebratedand what departure of the Jews the Seder commemorated. “The fault lines of exile and diaspora are always deep, and we always come from somewhere else and have come from somewhere else before,” he noted.

In “From Egypt“The irony of the family preparing to depart at Passover shouldn’t be lost on the writer, the reader and, one suspects, the characters themselves. After a quite somber attempt at a seder, the narrator wandered the streets of Alexandria, mourning a spot that had turn into home to him. Up until that time, the concept that Egypt could possibly be a spot of exile had not yet occurred to him; the concept that Israel is a spot of return for the stranger.

On that final evening, the narrator strolled along the waterfront and was offered “fiteers” sold on street corners in honor of the Muslim holiday of Ramadan. It shouldn’t be kosher at Passover, when leavened grains are forbidden, however the boy enjoyed the fried dough, the taste of which he remembered with joy a few years later.

The mixture of foreign and native cultures shows that the family was not unlike the opposite cosmopolitan mixed-race Jews living in Egypt on the time. The city was “so inextricably linked to who I was at that moment,” the narrator remembers. “And suddenly I knew… that I would always remember this night.”

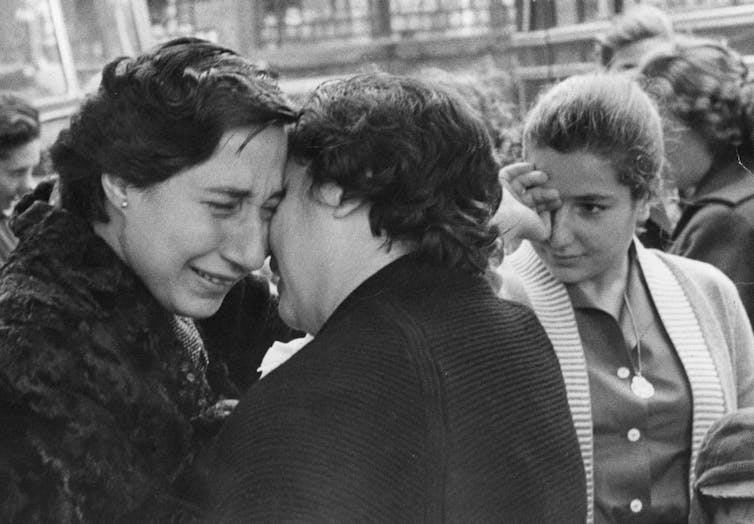

Max Scheler/Image article via Getty Images

It is a poignant account of the very personal nature of exile. And yet it’s an experience perhaps shared by everyone within the Jewish community. Exile is an unknown place, beyond the abyss.

To Iraq

Passover can be the main focus of the work of British journalist Tim Judah Visit to Iraq to cover the 2003 American invasion. He was the primary of his family to “return” to Baghdad in a few years. His father's family had left Iraq within the nineteenth century and went to India in the middle of the persecutions through the reign of Dawud Pasha.

Noting that his visit would coincide with the vacation, Judah set out to satisfy as most of the estimated three dozen Jews still living in Iraq as possible. The journalist found faint traces of the once thriving community: palimpsests with Stars of David in masonry, a Hebrew inscription in Ezekiel's tomb. At the time of Iraq's independence in 1932, Jews formed a plurality within the capital; On Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath, business got here to a standstill.

Culture Club/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

The Rise of Arab Nationalismthe creation of the State of Israel and changing geopolitics led to this the mass emigration the Jewish community within the early Fifties. In 2003, the few Jews Judah found were living in fearful and dilapidated homes.

“I tried to imagine my ancestors, in the fields or maybe in the shops or at the market, but I couldn’t.” Judah wrote within the magazine Granta. “A cold gray dust filled the air. Wrecked cars and burned-out tanks littered the road back to Baghdad. …So my ancestors lived here for 2,500 years? So what? My pilgrimage was over. I’ll never have to do it again.”

Judah's pilgrimage doesn’t result in a renewed sense of belonging, but quite to a rupture. The uprooting of his family is complete.

And so it continues, the cycle of exile and memory, of uprooting and re-rooting. With Passover, the free can rejoice their freedom and the rooted can rejoice their roots. But at the identical time, families across the Seder table can remember those that usually are not yet free and still suffer from uprooting.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply