One hundred years ago, the U.S. Congress passed essentially the most infamous immigration law in American history. Signed by President Calvin Coolidge Immigration Act of 1924 drastically reduced immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe and practically banned from Asia.

The way the law did this, nevertheless, was somewhat subtle: a quota. Lawmakers calculated what number of immigrants from each European country were living within the United States in 1890 after which took 2% of that number. Only so many newcomers from a given country might be taken in annually. Before the top of the Nineteenth century, the variety of immigrants from outside Western and Northern Europe increased was still relatively small – meaning their 2% odds could be tiny.

In short, the immigration law was blatantly racist and geared toward stemming the demographic tide. One of his sponsors, U.S. Rep. Albert Johnson, warned the House Immigration Committee: “a stream of foreign blood“poisoned the nation.”

Americans have at all times been torn between the “American Dream” and the fear of an ungovernable “melting pot.” Immigrants viewed immigrants ambivalently. In 1924 as continues to be the case todayMany residents thought between “good” and “bad” immigration. In their opinion, the 12 months 1890 marked a dividing line between the 2.

Look back as historian immigration and religionI’m struck by three changes in U.S. views on immigration over the course of the Nineteenth century.

Religion, greater than race

In the twentieth century, eugenicists were obsessive about race. In contrast, the natives of the early Nineteenth century were more concerned with religion and religion learn how to protect America's culturally Protestant foundations from Catholic immigrants – Most of them got here from Ireland and Germany at this point. At the center of this fear was an old paranoia: Could foreigners who profess allegiance to an infallible pope grow to be loyal residents of a republic?

Wikimedia Commons

Maybe so, the Cincinnati preacher Rev. Lyman Beecher dared – but only with great commitment to them.

“What is to be done?” he asked in his influential 1835 treatise.A plea for the West“To educate the millions that Europe will pour upon us in twenty years?”

Many nativists of the time shared similar fears about immigration and stated that the Catholic Church was “orchestrating.”a foreign conspiracy” against U.S. freedoms, aiming to strip constitutional freedoms and manipulate elections within the name of Vatican interests.

For Beecher, creating “intelligent, virtuous, and industrious emigrants” required public education combined with Protestant influence. In this manner, he suspected, Catholic populations could grow to be patriotic Americans who may also embrace Protestant churches. Such considering was commonplace.

Local, not federal

A second contrast between earlier nativism and its later Nineteenth-century counterpart was the virtual absence of major national immigration laws. For all their fears of the influence of foreign Catholics, natives within the early American republic valued assimilation moderately than exclusion. They saw immigration as a cultural, religious and academic concern greater than an arena for federal politics.

Wikimedia Commons

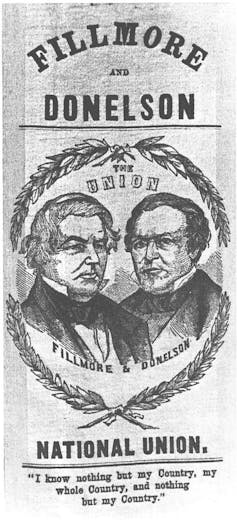

The anti-immigrant American party, or Know Nothing ticket, flourished within the 1850s before imploding over the problem of slavery. Know-Nothings enjoyed major gains in state and native elections, winning mayoral elections in cities akin to Boston and Philadelphia.

In Beecher's hometown of Cincinnati, nevertheless, the ticket is valid for natives couldn't get loose the incumbent Democratic mayor. There and elsewhere, Know-Nothing's dependence on Protestant German support against Catholic immigrant votes revealed the weakness of coalition politics and the subjective nature of the excellence between “good” and “bad” immigrants. Likewise, the one major Immigration proposal of the American Party — a compulsory 21-year waiting period for brand new immigrants looking for citizenship — never got beyond the drafting board.

Although overseas immigration Decline within the mid-1850sKnow Nothing activism was not necessarily the reason for this downturn. Instead, it reflected declining immigration Business cyclesakin to the top of the worst famine in Ireland.

end of an era

The final variable that shaped popular attitudes toward immigration was westward expansion. Most Americans viewed the frontier as a pressure valve for his or her growing country, promising land and opportunity to enterprising settlers. But within the late Nineteenth century, the era of Manifest Destiny – the assumption that the land's destiny was to spread from sea to sea – had reached the top of his journey.

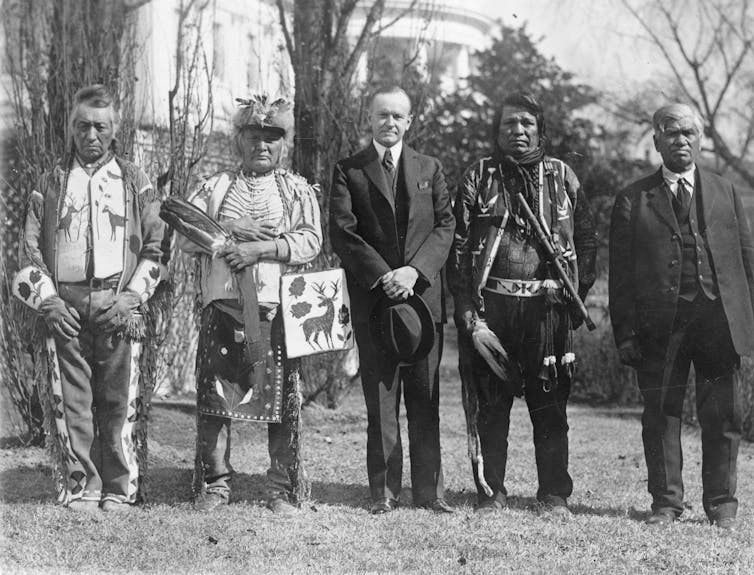

Collection of the National Photo Company/Wikimedia Commons

What is telling is that the 68th U.S. Congress, which passed the Immigration Act of 1924, also passed the law Indian Citizenship Act the next month. The law confirmed that every one Native Americans were U.S. residents at birth, while increasing their dependence on reservation lands as wards of the federal government.

The closure of the border marked a turning point in immigration history, but in addition a fundamental shift in American Indian relations. The government integrated native residents into the material of society but denied them the total advantages of citizenship. including guaranteed voting rights.

New era, latest prejudice

By the top of the Nineteenth century, the youngsters of Nineteenth century immigrants – primarily Northern Europeans – had largely integrated into American society, despite major problems anti-German prejudices this was common throughout the First World War.

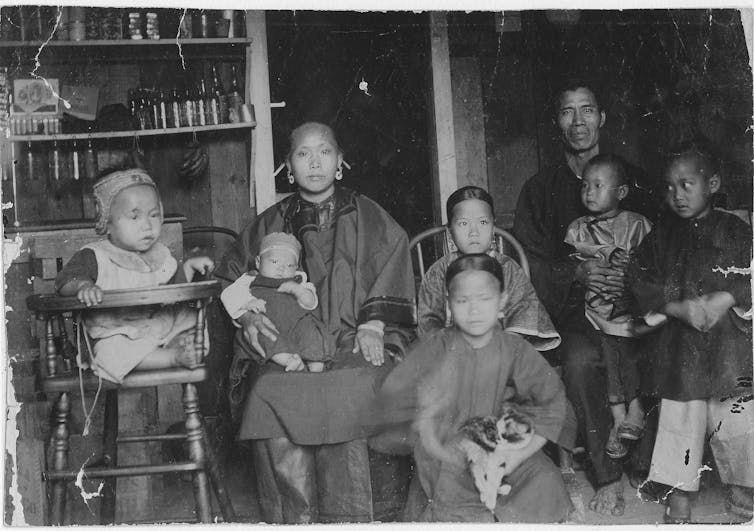

Meanwhile, the number of recent immigrants from other parts of Europe and beyond increased and experienced discrimination. Immigrants from East Asia particularly were suspected. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 imposed a moratorium on all immigration from China, claiming that Chinese immigrants threatened “the good order of certain places.”

Hawaii State Archives/Wikimedia Commons

In general, racial moderately than religious prejudices dominated anti-immigrant policy within the late Nineteenth century – although within the case of Anti-Semitism against Jewish immigrants from Eastern and Central Europe. The popularity of “racial Darwinism” was at its peak: pseudoscientific considering that misinterpreted Charles Darwin's ideas about evolution and promoted ideas akin to “Survival of the fittest” to human society. Many Americans with ancestry from Northern Europe embraced the resulting dogma of “Nordic” superiority.

The racism behind the 1924 Immigration Act even led to a reference in F. Scott Fitzgerald's “The Great Gatsby“, the famous novel published the next 12 months.

“Have you read 'The Rise of the Colored Empires' by that man Goddard?” asks Gatsby's antagonist Tom Buchanan. This thinly veiled reference alludes to “The Death of the White Race,” a 1916 manifesto by avowed white supremacist Madison Grant—and that was quoted approvingly within the congressional debates of 1924.

The record since then

The quota system was not repealed until 1965, when President Lyndon Johnson signed the law Immigration and Nationality Actand praised “those who can contribute most to this country – to its growth, to its strength, to its spirit.”

Since then, U.S. immigration has avoided overt discrimination based on national origin, with one exception: Donald Trump's 2017 supreme command Entry visas from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen shall be temporarily blocked.

Yet the Immigration Act of 1924 stays a historic benchmark that reflects centuries-old tensions between civic inclusion and racial exclusivity in American life.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply