In 1915 The Norwegian artist Emanuel Vigelandprobably the most respected Scandinavian artists of his time, created a picture of Christ with golden hair and fair skin.

Vigeland was aware of a widely circulated Bible illustrated by French artist James Tissot shows Christ as a Middle Eastern man with dark hair and brown skin. Tissot had spent a few years within the Holy Land within the late nineteenth century, researching the “historical Jesus” as a part of a brand new group of artists seeking historical accuracy.

However, Vigeland sought a unique tradition, one which viewed a picture of Christ not as photographic truth, but as a picture that communicated to the Norwegian community that Jesus was a brother.

Vigeland shows a handsome young man in front of a landscape of the New Jerusalem, as described within the Bible. He used the elegant sort of the time, Art Nouveauto appeal to its modern community and help the Norwegian viewer connect with the image.

In my work as a spiritual historian As a scholar, I actually have learned that artists throughout history have created images of Christ that spoke to different communities.

Early image of Christ as an emblem

Sometimes cultural constraints prevented people from representing Christ in any respect. In ancient Rome, early Christians often popular symbols or monograms of Christ's name, possibly because they didn’t need to confuse the image of Christ with that of the emperor.

In the fourth century, figurative representations became increasingly popular, but symbols continued for use. A stone sarcophagus within the Vatican Museums, for instance, shows events leading as much as Christ's death. However, in the middle, Christ's triumphant resurrection from the dead shows only his cross with Christ's monogram. It consists of the primary two capital letters Χ and Ρ – called Chi and Rho – of the Greek word for Christ: ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣX.

Christ with two natures

Michel M. Raguin, CC BY

The monumental Hagia Sophia in Constantinople – today's Istanbul – was originally built as a cathedral. It was initially inbuilt 537 by Emperor Justinian without figurative images. About 300 years later Several mosaic images have been added – one which testifies to the cathedral’s tradition of intensive theological study.

It copies a revered icon housed within the St. Catherine Monastery on Mount Sinai, Egypt. The icon, most certainly created in Constantinople as a present from Justinian to the monastery, features an unusual asymmetry as an example Christ's dual nature as God and man. The two sides of Christ's face will not be the identical, and the differences should illustrate his human nature and his divinity. Although different, each were truly united in a single body.

These were commissioned by the cathedral's scholars to depict Christian mysteries and preserve tradition.

Christ as God and child

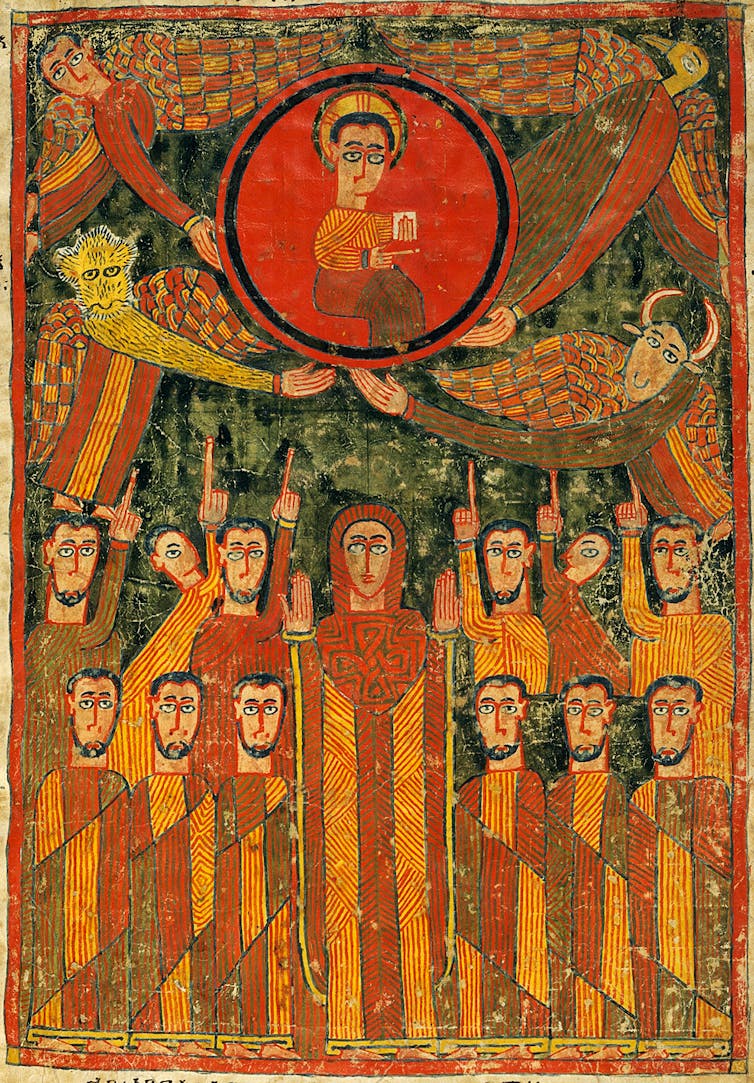

Illuminated Gospel, Amhara peoples – late 14th-early fifteenth centuries. Metropolitan Museum New York.

In an Ethiopian Gospel book, Christ was portrayed as eternally young, identical to him exercises all power in heaven and on earth. In some ways it resembles Vigeland's image of the youthful ruler.

Christianity got here to Ethiopia within the fourth century. From then on, Ethiopia continued to make use of abstract forms to convey the mystery of Christ, who lived and died but in addition lives endlessly. The manuscript's depiction of the Ascension – Christ's return to his Father in heaven after his resurrection – shows him as a baby holding a book in a red circle.

He is surrounded by the winged symbols the 4 evangelists: Matthew (man), Mark (lion), Luke (bull) and John (eagle). Below, Christ's disciples point upward to substantiate his ascension into glory. Their daring colours and powerful abstraction suggest Picasso's paintings – proof that art, like Christ, will be each deep in its time and beyond.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply