The last pandemic was bad, but COVID-19 is just certainly one of many infectious diseases which have emerged because the turn of the century.

Since 2000 the world has experienced 15 novel Ebola epidemicsthe worldwide distribution of a 1918-like influenza strain and enormous outbreaks of three latest and unusually deadly coronavirus infections: SARS, MERS and naturally, COVID-19. Every yr researchers discover two or three completely latest pathogens: the viruses, bacteria and microparasites that sicken and kill people.

While a few of these discoveries reflect higher detection methods, genetic studies confirm that that is indeed the case for many of those pathogens latest to the human species. What is much more worrying is that these diseases are occurring an increasing rate.

Despite the novelty of those particular infections, the first aspects that led to their development are quite ancient. Works in the sphere of anthropologyI actually have found that these are primarily human aspects: the way in which we eat, the way in which we live together and the way in which we treat one another. An upcoming book states: “Emerging infections: Three epidemiological transitions from prehistory to the current“My colleagues and I are studying how the identical elements have influenced disease dynamics for 1000’s of years. twenty first century technologies have only served to magnify old challenges.

Neolithic infections

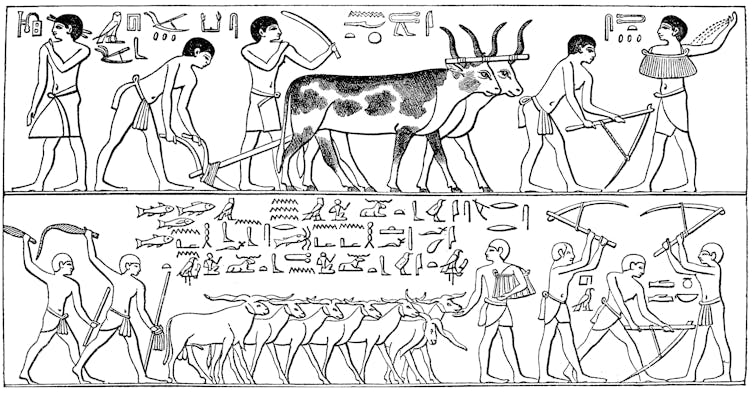

The first major wave of emerging infections happened with the start of the Neolithic Revolution About 12,000 years ago, when humans began to shift from foraging to agriculture as their primary livelihood.

Previously, human infections were mild and chronic in nature, with a manageable burden of long-term parasites that individuals carried from place to position. But full-time farming brought with it the varieties of acute and malignant infections we’re conversant in today. This global shift was humanity's first epidemiological transition.

mikroman6/Moment via Getty Images

Agriculture itself was not the cause. Rather, it was the main lifestyle changes that got here with this latest enterprise. Agriculture provided individuals with food high-calorie grainsbut often did on the expense of dietary diversityleading to weakened immunity as a result of nutrient deficiencies.

The human population increased dramaticallyand subsequently the number of huge and densely populated communities that would sustain the transmission of deadlier pathogens.

Our ancient ancestors domesticated animals for food and work their proximity to one another There is a possibility that livestock diseases can turn into human diseases.

Finally, this social hierarchies of newly agrarian societies led to inequalities within the distribution of essential resources for a healthy life.

These challenges to subsistence, settlement, and social organization were the first causes of humanity's first major disease transition.

Declining infections

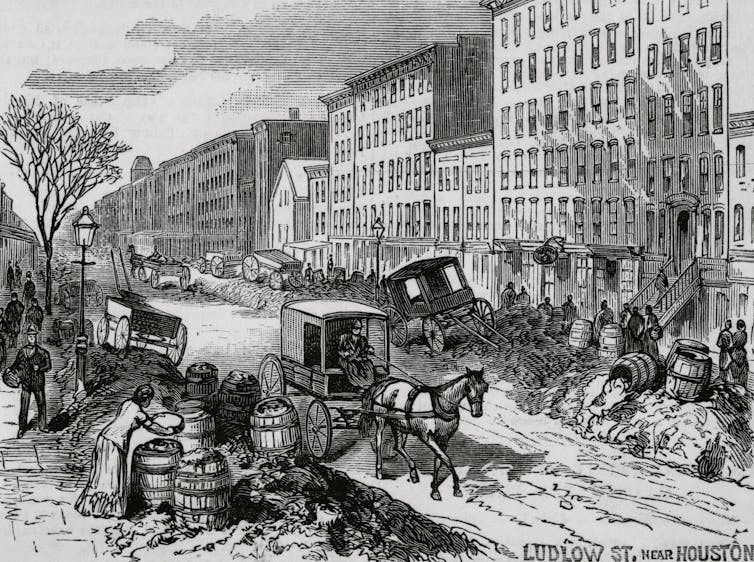

Over a dozen millennia, these patterns spread the world over like a plague of plagues. They lasted until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when life expectancy increased with the steepening Decrease in infectious diseases in high- and middle-income countries.

Remarkably, the biggest proportion of This decline has happened before the invention of effective antibiotics and a lot of the vaccines we use today. Health improvements were mainly as a result of non-medical aspects akin to: higher farming and food distribution methods, large plumbing projects And Housing reforms in poor urban areas.

Bettmann via Getty Images

These were major reversals within the usual categories—subsistence, settlement, and social organization—that led to the rise of infectious diseases in the primary place. They led to humanity's second epidemiological transition, a big but only partial reversal of the changes that first began within the Neolithic period.

This second pattern was not a panacea. Despite general health improvements, chronic non-infectious diseases akin to heart disease and cancer proceed to occur became the predominant reason behind human mortality.

Most low-income countries experienced a later version of this transition after World War II, but its health advantages from declines in infections were noticeable significantly less than those of their wealthier counterparts. At the identical time, their losses from non-infectious diseases increased at a comparable rate. These contradictory trends have resulted in a “worst case scenario” when it comes to the health of poor societies.

Also price noting is the decline in infections in low-income societies more reliant on reasonably priced antimicrobial medications. Given the emergence of drug-resistant pathogensThese medical buffers are proving to be little greater than short-term solutions to the health consequences of poverty.

Since pathogens can move freely across borders and borders, these consequences can quickly grow to be everyone's problem.

fotograzia/Moment via Getty Images

Converging infections

In recent a long time, humanity's interconnectedness has reached a degree where almost everyone lives in a single global disease environment. Borders and borders not limit the spread of distant outbreaks. The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically illustrated this latest reality, because the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread around the globe in only a number of weeks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also demonstrated how infectious and non-infectious diseases can interact synergistically to supply even worse outcomes than the easy sum of individual diseases. This is evident from nearly all of COVID-19 deaths which have occurred here People with chronic heart, lung and metabolic diseases which might be common to a growing proportion of older people in each affluent and poor populations.

Taken together, these challenges have laid the muse for the converging disease patterns seen today. This is the third epidemiological transition: the rise of latest, virulent and drug-resistant infections in a rapidly aging and highly interconnected world.

Unfortunately, the present pattern is resulting in increasing outbreaks of latest and deadly infections. The predominant causes of those outbreaks lie in areas akin to commercial agricultural practicesThe Urbanization of the human population and the challenges of Poverty within the face of economic growth.

Despite the magnitude of those determinants, these are essentially the identical questions of subsistence, settlement and social organization as they were 12,000 years ago. Addressing these recurring problems will do greater than prepare the world for future pandemics; It will help prevent them in the primary place.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply