On February 23, 2024, Daqua Lameek was a knight found guilty of a hate crime for the murder of Dime Doe, a transgender woman from South Carolina who’s believed to be in a relationship with Ritter.

The verdict marks each first trial and first conviction a hate crime based on gender identity under the 2009 Act Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

Under the lawHate crimes are “acts of violence that are motivated by a victim’s actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability.”

Between 2013, the yr the FBI first began monitoring hate crimes motivated by gender identity, and 2022, the yr the FBI began recorded 1,969 hate crimes against trans and gender non-conforming people, including a raise in 2022.

Ritter's trial reflects the low prosecution rate for all hate crimes. Between 2005 and 2019 federal prosecutors investigated 1,878 suspects in hate crime casesleading to 310 prosecutions and 284 convictions for breaches of hate crime laws.

I'm a historian who studies this Development of hate crime activism in Australia, Europe and the USA. My research has found that hate crimes laws is strikingly ineffective at stopping violence by securing convictions, as evidenced by the incontrovertible fact that it has taken 15 years under federal law to secure a conviction based on gender identity.

The law was welcomed by leading politicians on the time Gay rights activist Joe Solmonese as “our country’s first major civil rights law” for LGBTQ people. But it was not, as many imagine, the results of clearly progressive impulses. Instead, it emerged from an unexpected convergence of gay and civil rights goals and a war on crime within the Reagan era.

Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

Hate Crime Statistics

In the twentieth century, same-sex and gender non-conforming people were often victims of violence and harassment by the police. Although early at the bottom Anti-violence initiatives While some protections were offered within the Nineteen Seventies, LGBTQ people had little legal recourse.

Until 1980 Anti-sodomy laws still existed in 29 statesand LGBTQ activists stood in front of you Setback against the limited successes of the Nineteen Seventies. The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, supported by a rising religious right, anchored this backlash in national politics. It also had two necessary consequences for LGBTQ politics.

First, medical coverage of what became referred to as AIDS established an enduring link between homosexuality and fatal disease amongst several gay men in 1981, further triggering the problem Resurgence of homophobia.

Secondly, fears of a national crime wave led many to support the Reagan administration tough crackdown on crimeincluding expanded policing and harsher punishments.

The claims of a nationwide crime wave were based on data collected by the US The FBI's Uniform Crime Report. Started in 1930, this system collected data voluntarily submitted by local and state law enforcement agencies.

However, discrepancies between regional jurisdictions, the shortcoming to trace crimes not reported to police, and inefficient data collection procedures, amongst other issues, led to questions on whether the system accurately reflected national trends.

More detailed system

In the early Eighties, the FBI and a number of other other law enforcement agencies began modernize the Uniform Crime Reporting Program. The agencies' combined efforts over the last decade resulted in an FBI-managed enterprise system In 1989, there was a transition from summary reporting to more detailed, incident-based reporting.

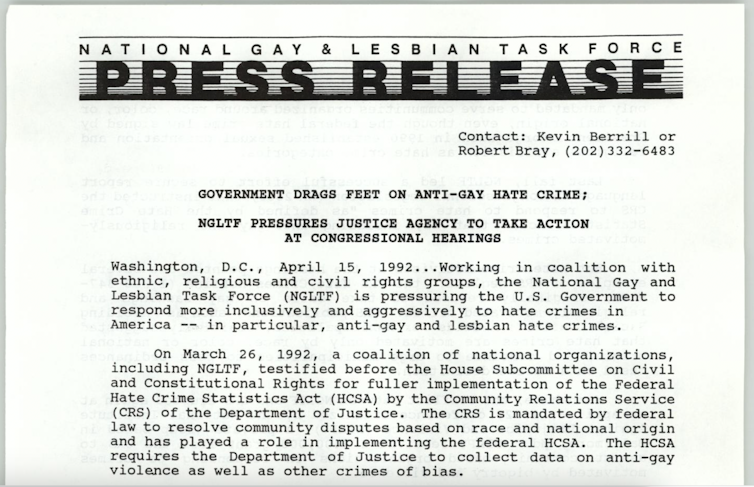

In 1986, at the peak of the AIDS crisis and amid national fears of violent crime, gay activists founded Kevin Berrill the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the biggest gay rights group within the country on the time, and Diana Christensenof San Francisco's Community United Against Violence, testified before Congress about anti-gay violence. They argued together that such violence represents a “second epidemic” after AIDS. Active data collection was essential to combating violence. Laws into consideration on the time to gather hate crime statistics excluded sexual orientation and needed to be revised before passage by Congress.

Statistics alone weren’t enough. According to Berrill and ChristensenAbout 80% of anti-gay attacks weren’t reported to police, and people who were reported were often turned away. The activists beneficial “stricter laws“That would allow federal prosecution if local authorities would not do so,” Berrill’s organization continued.praises the Reagan administration” for its concern for victims of violent crime and called on “federal, state and local authorities concerned with crime and its victims” to analyze and forestall violence against homosexuals.

These arguments were successful. With the support of other civil rights organizations Hate Crime Statistics Act It passed Congress with widespread support and was signed into law in 1990 by Reagan's successor, President George HW Bush. The law defined “hate crimes” as “crimes that reveal signs of prejudice based on race, religion, sexual orientation, or ethnicity” and authorized the attorney general to start collecting data on such crimes.

The Hate Crime Statistics Act was the primary update to the revised Uniform Crime Reporting Program and added bias as a motivation. While this led to robust prevention efforts, hate-motivated violence also became a federal crime category.

And that laid the muse for future anti-crime laws.

University of North Texas Libraries

Expanded hate crime laws

The recent law only allocated funds for statistics collection, not for policing and law enforcement.

Law enforcement agencies have been asked to offer data on a voluntary basis. This meant that given the documented problem of anti-gay bias in police, data may not have been provided. Activists in some cities including San Francisco, recent York And Dallas, were in a position to work with individual cops on violence prevention initiatives. But efforts on the national level have been piecemeal at best and hampered by Republican opposition.

In 1993, nonetheless Hate Crimes Sentencing Actthat established federal sentencing guidelines for hate crimes was added the bipartisan law to regulate and prosecute violent crimes that was pending in Congress. This law, passed in 1994, increased funding for police forces, law enforcement agencies, and correctional facilities. It was criticized for expanding the U.S. prison system and promoting punitive responses to crime.

With the Hate Crimes Sentencing Act attached to it biggest crime law in US history it became symbolic a bipartisan, tough-on-crime era.

Prosecution of hate crimes

In 1998, the highly publicized murders of Matthew Shepard, a gay college student in Wyoming, and James Byrd Jr.A black resident of Jasper, Texas, renewed pressure to expand federal powers to prosecute hate crimes moderately than simply collect data or set sentencing guidelines.

In 2001 the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act was introduced in Congress. Republican and conservative opposition meant the law was not passed until 2009. It expanded federal jurisdiction over hate crimes and provided additional resources to local police forces and courts to analyze and prosecute hate crimes.

The law included gender identity as a protected category, making it theoretically applicable to crimes against LGBTQ+ people. Under this law, Ritter was convicted of murdering Dime Doe, a transgender woman.

The law shouldn’t be effective in collecting data or enforcing penalties. Not only did the primary federal conviction for a hate crime based on gender identity occur 15 years after the law was passed, but hate crimes normally are also subject to chronic underreporting.

In 2022, the FBI reported 11,634 crimes classified as a hate crime. While the FBI explained Some say the Uniform Crime Report shouldn’t be exhaustive Researcher have identified that the system doesn’t adequately report data on hate crimes specifically. In 2022, roughly 80% of participating agencies reported no hate crimes diverges from other reputable data sources.

In short, and as researchers continually emphasize, the expansion of national criminal law since 1990 has not yet proven effective in stopping hate crimes and other violence.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply