All over the world, fashion researchers, designers and artists are exploring the connections between clothing, jewelry and well-being.

“Enveloped knowledge” deals with the psychology of clothing, and designers explore how to Create garments to heal the wearer.

First Nations people understand the ability of connection through cultural clothing and jewellery. Items comparable to opossum and kangaroo Skin coats can contribute to healing and cultural practice.

But it isn’t only traditional clothing that may result in healing. In Australia, there are a growing variety of designers and artists who’re Protectionist era Clothes on the catwalk and within the galleries.

By reimagining garments linked to painful and traumatic memories and stories, these designers and artists hope to bring awareness to those horrific policies, redefine their meaning, and discover a path to healing.

A story of missions, reserves and trauma

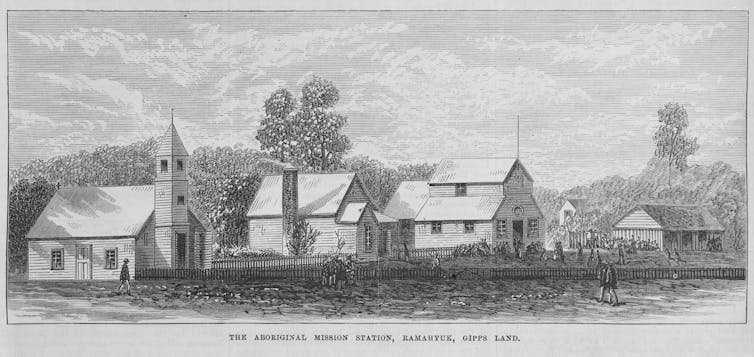

First Nations peoples living on controlled reserves, missions and stations were forced to wear civilian clothing and were expected to take care of it. neat and clean. Clothing was often a type of payment and punishment.

In some institutions, First Nations people produced clothing and jewellery for interstate and international exhibitions and tourism.

This Regime and power through clothing had significant impacts on the people living there, including their cultural practices, identity and well-being.

State Library Victoria

There are two national holidays to pause, acknowledge and remember the Stolen Generation and their families and communities – National Sorry Day on May 26 and the Anniversary of the National Apology to the Stolen Generation on February 13.

Healing and well-being require a holistic approach, and art contributes to this.

Using clothing as art or designing garments with a transformative and positive tone can profit members of the Stolen Generation and their families.

Healing through fashion design

The Yarrabah community in Queensland has experimented with fashion to inform stories of the Yarrabah Mission.

The Cairns Indigenous Art Fair 2019 invited the Djunngaal Yarrabah Elders Group to work on a set for the Buwal-Barra fashion show. The collection, called ByDaBell, represents the importance of the bell within the Yarrabah Mission, which tightly controlled its day.

The Elders of Yarrabah were recreated three vital dresses worn within the mission: an on a regular basis dress, a proper church dress and a punishment dress product of potato sacks. The elders told a robust story about their mission experiences and the way clothing was used for punishment or control.

For the Yarrabah community and plenty of First Nations people, Telling the reality is a type of healing and a reminder of resilience.

Healing through finding the reality was also a part of a commissioned work Wedding dress made for the exhibition “I Do! Wedding Stories from Queensland” 2020 on the Queensland Museum.

A collaborative effort between dressmaker and artist Simone Arnol (Gunggandji), artist and curator Bernard Singleton (Umpila, Djabugay/Yirrgay) and the Djunngaal Yarrabah Elders, the garment told stories of missionary experiences and colonial wedding customs.

Based on mission style wedding dresses, Dress presented a five-meter-long circular loop with a striking image of a mission prison. The stained lining product of traditional materials symbolized the suppression of First Nations culture.

Queensland Museum, CC BY-NC-ND

Healing through art clothing

The artist Yhonnie Scarce (Kokatha/Nukunu) created a piece in regards to the experiences of her grandmother Fanny and great-great-grandmother Florey as Domestic servants within the early 1900s.

The piece consists of two linen aprons modelled on those worn by Flora and Fanny, and 16 hand-blown glass plums tucked into the aprons and poking through the pockets. Their names have also been fastidiously hand-embroidered on each apron.

The Piece represents the strength of Flora and Fanny of their role as matriarchs who look after the family and hold on to their cultural identity.

Shell weave slippers by Esme Timbery (Bidjigal) incorporates 200 pairs of tiny, decorated shoes that the kids of the Stolen Generation and the Shell craft practice of Aboriginal women in La Perouse, Sydney.

Made from fabric and decorated with glitter and shells in various sizes, colors and patterns, the slippers tell the story of the experiences of forcibly displaced children and the strength and resilience of First Nations families and communities.

Although it isn’t a uniform of the kids who were taken out of their homes and placed in homes, the massive variety of small and empty shoes reminds the viewer of the suffering and trauma they suffered under protectionist policies.

Sharing stories, remembering history

First Nations fashion designers and artists are transforming protectionist-era fashion on the catwalk and in exhibitions. They need to use this to protest against racist and colonial policies and convey healing.

We must proceed to inform these stories in regards to the true history of this country and the way garments oppressed and controlled Indigenous people.

The movement to heal painful memories and intergenerational trauma through clothing contributes positively to the well-being of First Nations people.

First Nations individuals are resilient and can proceed to explore and have a good time their culture and identity through their clothing.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply