Collectors enjoy so-called “hidden mother photos” as historical curiosities.

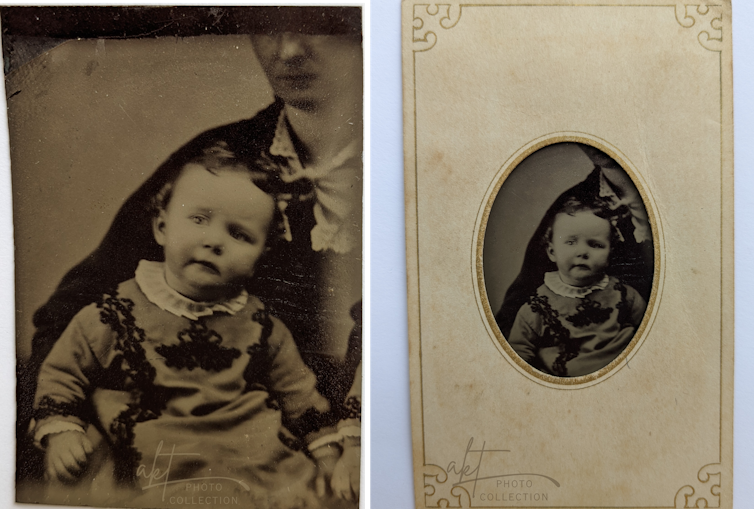

These Nineteenth-century images show very young children being held still by half-hidden adults, crouching behind chairs or lurking at the perimeters of the frame, their protective arms steadying babies. The adults' heads and shoulders are sometimes wrapped in textiles or unceremoniously cut off, or their bodies are partially hidden behind decorative mats that frame the centered child.

The startling revelation that Victorian toddlers lay on comfortable laps reasonably than on cozy blankets is sparking breathless online attention. Avid resellers of flea market finds advertise hidden mother photos with terms like “creepy, wonderful,” “cute, spooky” and “bizarre.” Articles about her are likely to imply a treasure hunt for the hidden—adult knees or noses, balanced hands, breasts, hat brims, and skirts.

But this common formulation reduces their cultural significance to sensationalism: Look how crazy our ancestors were!

JNO. W. Minner's City Gallery, Sparta, Illinois. (ca. 1862–64) © Andrea Kaston Tange. All images come from the creator's private collection.

As someone who has studied the history of those photos, I find myself drawing an unlikely connection between these stark sepia portraits and modern, candid snapshots of mischievous children delighting their adoring moms. Both stand within the tradition of sentimental image creation around the long-lasting mother and child figure.

The exposure times in Nineteenth century photography were very long by today's standards – 20 to 60 seconds – which explains why it took trusted adults to get young children into the silence obligatory to take a portrait. However, this technological limitation doesn’t explain why their moms were half-erased in these photos, which has led scientists to imagine this was the case for Victorian women erased from their cultureand casual viewers assume that the photographers who produced these visual gaffes were incredibly bad at their craft.

But my research has shown that Victorian photographers documented children at a moment when the need to attract cultural attention – and subsequently camera lenses – to them was widespread Childhood as a precious time that must be protected. And the partial veiling of the moms didn’t contradict the pictures of beloved children, because to understand is to carry.

These are, briefly, images of care.

© Andrea Kaston Tange. All images come from the creator's private collection.

Evolving photographic forms

Photography was a recent technology within the Nineteenth century. Early photographers coated thin metal plates with light-sensitive material, exposed them behind the camera lens, and developed the plates using precise chemical processes. Each shot produced a novel and irreproducible image directly on the metal.

The fragile daguerreotypes of the early 1840s brought one Time for constant experimentation. Photographers eventually perfected more stable color types – even non-reproducible images on metal plates – and later helped revolutionize the medium Glass negatives This allowed multiple prints of the identical image. These prints required special paper made light-sensitive with a coating of ammonium chloride stabilized in albumin or egg white. Through this process, photography became widely viable as a occupation, hobby, and art. In the Eighties, at the peak of its production, the Dresden Albumenizing Society needed it 60,000 eggs per day to satisfy global demand for its high-quality photo paper.

Comparing a color type from the 1860s with a gelatin silver studio print from the Eighteen Nineties shows the event of photographic processes.

© Andrea Kaston Tange. All images from the creator's private collection.

The studio portrait features sharp focus, strong contrast between light and dark, beautiful midtones to contour the infant's cheek, and artful studio lighting to capture the kid's alert eyes and the shine of a mother's cufflink. The color type is in every respect the alternative: its flattened quality and narrower tonal range are hallmarks of this less technically demanding photographic process.

But in each portraits, the loving mother's strong hands stabilize the kid.

Represent tender connections

Scientists don't know who first used the term “hidden mother,” although some think so was created around 2008. A photography exhibition on the Venice Biennale by Linda Fregni Nagler and a lyrical photo essay by Laura Larsoneach published in 2013 and titled “Hidden Mother,” cemented the moniker that paradoxically erases the kids at the middle of those portraits.

Especially a baby picture – a color type from the 1850s – tells a story concerning the development of photographic technology and its role in documenting the fleeting, tender moments of childhood.

© Andrea Kaston Tange. All images come from the creator's private collection.

The baby's softness is enhanced in comparison with its mother's strong jaw. The child's thoughtful look conveys a deep sense of security when he’s snuggled up against his mother's side. The contrast between soft and sharp focus shouldn’t be just an emotional contrast, however the effect of the slight movement of the baby throughout the necessarily long exposure time.

The baby's composure is partly as a result of the presence of a 3rd figure on this photo. This child appears to be a twin: certainly one of her tiny hands is protectively covered by one other equally small hand, at the tip of one other arm clad in an analogous braided dress. On their mother's lap, these babies lie in a triangular embrace that evokes the intimacy of family bonds.

When you place the unique oval cutout mat back on top of the photo, the infant appears to drift, breaking away from the hugs that support him. It also suggests where the nickname for these images, “hidden mother,” comes from. But hands, bodies and the ability of touch are the main focus of such images.

Appreciation of the mother-child bond

Modern observers often assume that Nineteenth-century customs marginalized motherhood. But I argue that this can be a projection of ahistorical ideas.

It is a strikingly modern tendency to have fun the flexibility of ladies I actually have each children and a profession, without making an allowance for how an individual then manages two full-time jobs. Such celebrations obscure the work and time that parenting requires, as a substitute pushing for the platitude that doing what we love for those we love isn't work.

I think that contemporary prejudices may conceal moms excess of Nineteenth-century portrait conventions. These images remind thoughtful viewers that babies are held and nursed, soothed and guarded, nurtured and guided toward independence, not by abstract notions of being the fitting form of mother, not by curiosities, but by embodied people.

The historical phenomenon of hidden moms could usefully be renamed “treasured child photos.” This designation identifies the topics of their children more precisely and focuses on the connection, the esteem that’s dear to them. It also offers a fruitful avenue for loving contemplation of moms, children, and the myriad types of mothering work and the bodies they perform on Mother's Day and beyond.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply