When Russian President Vladimir Putin was not invited to attend the seventy fifth anniversary commemorations of D-Day in France in 2019, he claimed this was “not a problem” for the reason that Allied invasion of France on June 6, 1944 “wasn't a game changer.”

As the United States, Britain, Canada, France and other nations mark the eightieth anniversary of D-Day this 12 months, Putin will again not attend, this time due to the war of aggression he waged in Ukraine. But it's price remembering the actual story of how Soviet media covered the invasion of Normandy, wherein masses of Allied troops stormed the beaches and commenced the means of retaking Europe from the Nazis.

I study Media and propaganda within the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union within the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. What Soviet residents learned about D-Day was a part of a rigorously controlled media system. Soviet newspaper articles, political cartoons, and radio reports recognized the importance of opening a second front in Europe, but downplayed its importance within the larger context of the war. They also reminded Soviet residents that the invasion was long overdue.

No news on the front page

On the morning of June 7, 1944, the front page of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's official newspaper, Pravda, which suggests “truth” in Russian, mentioned only the news of the D-Day invasion in a small text box on the front page. The essential front-page articles covered improvements to Soviet cities following Red Army victories and the continuing military campaigns near Kishinev and Jassy – now often called Chișinău (Moldova) and Iași (Romania).

On page two were telegrams thanking Soviet dictator Josef Stalin for his support of the youngsters of frontline soldiers. This page also contained the fifth a part of an ongoing series about Red Army victories entitled “The Road to Victory.”

Pravda

D-Day got here on page three in an article headlined “The Invasion of Europe Has Begun.” The correspondent, Major General Mikhail Galaktionov, reported that the Allies had carried out an enormous operation to liberate Western Europe from the Nazis and concluded that “the invasion of Europe is now taking place under unprecedented conditions in the history of warfare.”

The article was accompanied by a map of northern France with names that American readers would soon learn: Cherbourg, Carentan, Arromanches and others. Pravda's report accurately linked the Normandy landings to the progressive liberation of Italy and noted that the essential concentration of the German army was now attempting to defend Western Europe. Of course, because the newspaper report appropriately noted, the German army was significantly weakened “after three years of war on the Soviet-German front.”

A photograph of Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower was on page 4, together with other reports on the second front in Europe.

For Pravda, the Allied attack on the defenses of Hitler's Atlantic Wall on the French coast was just one among many moments in a war that Soviet readers knew all too well from years of fighting on their very own soil.

The Moscow News

For the English-speaking audience

In the Moscow News, the Soviet government's English-language newspaper, D-Day played a much larger role, although it needed to be within the highlight. A front-page article featured a photograph of Eisenhower. “Allied Troops Land in Northern France, Capture Invasion Beachheads” was the boldest headline on June 7, 1944. However, it was printed alongside an article in regards to the Red Army's major victory at Jassy, Romania.

Other front-page articles discussed Soviet industry's successes in winning the war and the way the Allies' capture of Rome represented “a major military and political victory.”

An article on page three of the English-language newspaper stated: “June 6, 1944, will go down as a memorable date in the history of World War II.” K. Hofman, the reporter, quoted Winston Churchill's announcement of the operation, described how news of the attack “went around the globe with lightning speed,” and praised Eisenhower's leadership particularly.

As the Moscow News reported, D-Day meant that the German armies now faced a “lethal threat from combined devastating blows from the Red Army from the east and the Allied armies from the west.”

No Boltai! Collection, Prague

A change in tone

The Soviet media's praise of each Churchill and Eisenhower could have surprised some readers. The USSR's leaders, journalists and propagandists had all the time criticized the Allies for his or her failure to open a “second front” against the Nazis in Europe The Allies promised this in 1942.

An October 1942 issue of Pravda stated: Soviet political cartoonist Boris Yefimov published his cartoon “A Meeting of War Experts” on the “Discussion of the Second Front in Europe.” In it, “General Brave” and “General Determined” attempt to persuade a gaggle of older generals sitting at a table: They are labeled “General What-If-We-Lose”, “General Is-It-Worth-Risking”. “General: Let’s not rush into anything,” “General: Let’s wait,” and “General: What-if-something-goes-wrong.”

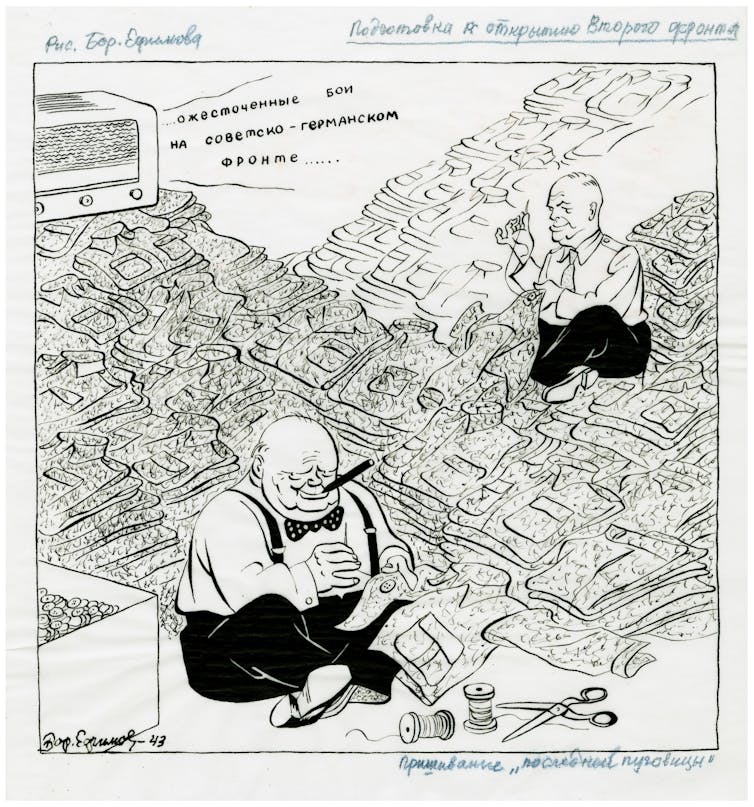

In other cartoons published in 1942 and 1943, Yefimov explicitly identified Churchill and Eisenhower because the architects of the delay. In the cartoonist's “Preparations for the Opening of the Second Front,” for instance, the British prime minister and the American general sit on the ground sewing buttons on uniforms while listening to a radio broadcast in regards to the “fierce fighting on the Soviet-German front.” The implicit message is that the British and Americans are deliberately buying time in order that the USSR can bear the brunt of Hitler's violence. Rather than releasing the pressure, as Yefimov and other press accounts claimed, Churchill and Eisenhower sat, smiling, and listened to the radio.

No Boltai! Collection, Prague

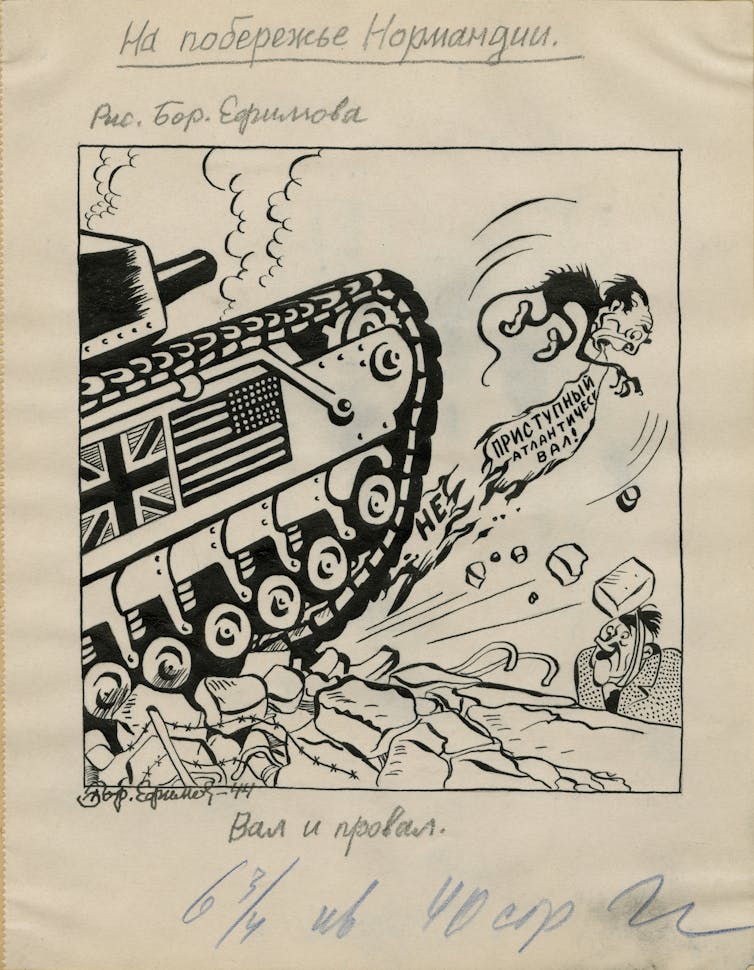

After June 6, and in keeping with other Soviet press reports, Yefimov published two cartoons highlighting D-Day. “On the Beaches of Normandy” is dominated by a tank with British and American flags. As it crushes the German fortifications beneath its wheels, the tank also sends off a beast-like Joseph Goebbels, who tears up his speech in regards to the “unbreakable Atlantic Wall” while Hitler crouches dejectedly in a corner.

No Boltai! Collection, Prague

In one other cartoon entitled “On Walls and Waterfalls,” published on June 12, 1944, Yefimov reminded Soviet readers of their country's contribution to the war effort. Goebbels, General Erwin Rommel, Hitler and Hermann Göring stand on a wall that also bears an indication warning of the “impregnable Atlantic Wall”. Behind his back, nevertheless, Hitler kept an inventory of other “impregnable” fortresses, all of which had been captured by the Red Army in 1943. D-Day was a vital event, as Yefimov's cartoon illustrates, however it suggests probably the most significant destruction of the Nazi war machine had been created by the Soviets.

No Boltai! Collection, Prague

Prelude to the Cold War

Memories of the delay in opening a second front would long linger within the USSR and develop into grievances in regards to the Cold War. After Churchill made the famous speech in March 1946 wherein he described Soviet influence as “Iron CurtainAcross Europe, Yefimov continually mocked him, calling him the identical nefarious guy who sewed on buttons while Soviet soldiers and residents suffered. Soviet propaganda transformed Eisenhowerwho was US President from 1953 to 1961, a stereotypical warmonger.

Over the a long time, the Soviet media downplayed or ignored D-Day. Instead, they highlighted the sacrifices made by Soviet residents fighting the Germans, the “anti-Soviet” sentiments that delayed the opening of the Second Front, the victories won at Stalingrad, and other Soviet-centric perspectives. D-Day remained news at best on page three, “not a game changer” then – or, for Putin – now.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply