The three staple foods that dominate the fashionable food regimen – corn, rice and wheat – are familiar to Americans. However, Fourth place goes to a dark horse: cassava.

Although cassava is sort of unknown in temperate climates, it’s a very important food source throughout the tropics. It was domesticated 10,000 years ago, on the southern fringe of the Amazon basin in Brazil, and from there spread throughout the region. With a shaggy trunk several meters tall, a handful of slender branches and modest, palmate leaves, it doesn't appear to be anything special. However, cassava's humble appearance belies a formidable combination of productivity, toughness and variety.

Philippe Giraud/Corbis Historical via Getty Images

Over the millennia, indigenous peoples have bred it from a weedy wild plant right into a plant Crop that stores enormous amounts of starch in potato-like tubers, thrives within the poor soils of Amazonia and is sort of invulnerable to pests.

The many advantages of cassava appear to make it the best crop. But there’s an issue: Cassava is extremely poisonous.

How can cassava be so toxic and yet dominate the food regimen in Amazonia? It's all because of the ingenuity of the indigenous people. Over the last 10 years, my collaborator César Peña and I studied Cassava gardens on the Amazon and its countless tributaries in Peru. We have discovered quite a few varieties of cassava, breeders using sophisticated breeding strategies to regulate toxicity, and developed sophisticated methods of processing their dangerous but nutritious products.

Long history of plant domestication

One of the most important challenges early humans faced was getting enough to eat. Our ancient ancestors lived by hunting and gathering, catching prey on the run and collecting edible plants at every opportunity. They were surprisingly good at it. So good that their populations increased rapidly from the birthplace of humanity in Africa 60,000 years ago.

Still, there was room for improvement. Searching the landscape for food burns calories, namely the resource you seek. This paradox forced hunter-gatherers to make a compromise: burn calories trying to find food or save calories by staying home. The compromise was almost insurmountable, but people found a way.

Just over 10,000 years ago, they cleared the hurdle with one of the vital transformative innovations in history: Domestication of plants and animals. People discovered that when plants and animals were tamed, they not needed to be hunted. And they could possibly be selectively bred and produced larger fruits and seeds and bulkier muscles to eat.

Cassava was essentially the most domesticated plant on the earth Neotropics. After its initial domestication, it spread throughout the region, reaching areas as distant as Panama inside a number of thousand years. While cassava cultivation didn’t completely eliminate people's have to forage within the forest, it eased the burden and provided an abundant and reliable food supply near home.

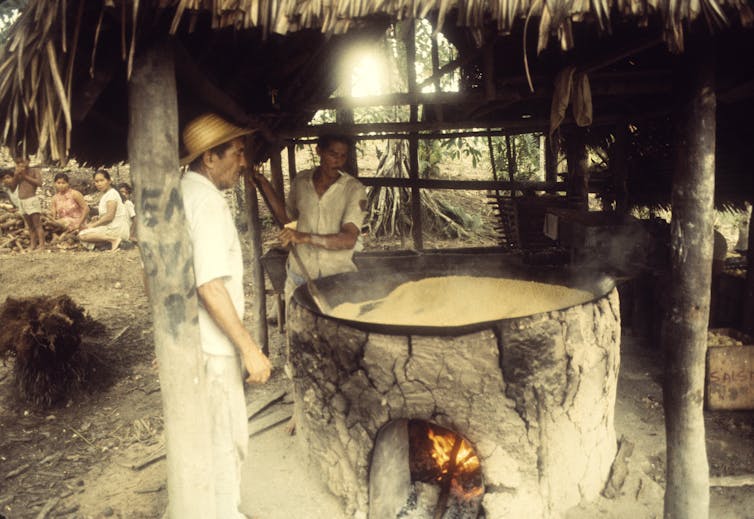

Today, almost every rural family throughout the Amazon has a garden. Visit any household and you’ll find that cassava is fire-roasted, toasted right into a chewy flatbread called casabe, fermented into beer called masato, and stewed in soups and stews. However, before using cassava for this role, it was vital to work out find out how to cope with its toxicity.

Processing a toxic plant

One of the most important strengths of cassava, its pest resistance, is guaranteed by a robust defense system. The system is predicated on two chemicals produced by the plant: Linamarin and Linamarase.

These antibodies are situated within the cells of the leaves, stems and tubers of the cassava plant, where they normally remain dormant. However, when cassava's cells are damaged, reminiscent of by chewing or chopping, linamarin and linamarase react and release a wave of harmful chemicals.

One of them is notorious: cyanide gas. The explosion also incorporates other harmful substances, including compounds called nitriles and cyanohydrins. Large doses of it are fatal, and chronic exposures are everlasting damage the nervous system. Taken together, these poisons deter herbivores in addition to cassava almost insensitive to pests.

No one knows how humans first solved the issue, but ancient Amazonians developed a fancy, multi-step detoxing process that transformed cassava from inedible to delicious.

Stephanie Maze/Corbis Historical via Getty Images

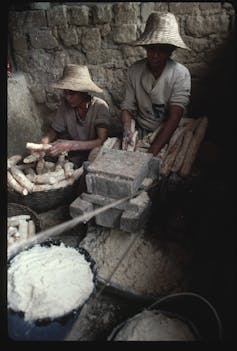

It begins with grinding the starchy roots of cassava on shredding boards affected by fish teeth, stone shards, or, commonest today, a rough sheet of tin. Crushing mimics the chewing of pests and ends in the discharge of cyanide and cyanohydrins from the foundation. But they enter the air and never the lungs and stomach like after they are eaten.

The chopped cassava is then placed in rinsing baskets where it’s rinsed, squeezed by hand and drained repeatedly. The motion of the water releases more cyanide, nitriles and cyanohydrins and is washed away by squeezing.

Finally, the resulting pulp might be dried, which further detoxifies it, or cooked, which completes the method with heat. These steps are so effective that they’re still used throughout the Amazon today. Thousands of years since their first invention.

Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A robust plant that spreads quickly

The traditional methods of grinding, rinsing and cooking utilized by Amazonians are a complicated and effective technique of converting a toxic plant right into a meal. But the Amazonians took their efforts even further and tamed it right into a true domesticated crop. Not only did they devise recent methods of processing cassava, but additionally they began to maintain track and steadily selectively cultivate varieties with desirable characteristics create a constellation of types used for various purposes.

In our travels, we found greater than 70 different varieties of cassava, extremely diverse each physically and nutritionally. These include species of various toxicity, some requiring laborious chopping and rinsing and others that might be cooked as is, although none might be eaten raw. There are also varieties with different tuber sizes, growth rates, starch production and drought tolerance.

Their diversity is valued, and so are they often given imaginative names. Just as American supermarkets carry apples named Fuji, Golden Delicious, and Granny Smith, Amazon gardens stock cassava named Bufeo (dolphin), Arpón (harpoon), Motelo (turtle), and countless others. This creative breeding cemented cassava's place in Amazonian cultures and diets, ensuring its manageability and utility, in addition to domestication Corn, rice And Wheat consolidated their place in other cultures.

While cassava has been common in South and Central America for hundreds of years, its history is way from over. In the age of climate change and increasing sustainability efforts Cassava is emerging as a possible world crop. Its durability and hardiness make it easy to grow in changing environments, even when soils are poor, and its natural pest resistance reduces the necessity to protect it with industrial pesticides. Additionally, although traditional Amazonian methods of detoxifying cassava might be slow, they’re easily reproduced and accelerated with modern machinery.

Juan Silva/The Image Bank via Getty Images

In addition, Amazon growers' penchant for preserving diverse varieties of cassava makes the Amazon a natural repository of genetic diversity. In modern hands, they might be bred to provide recent species suitable for purposes beyond those present in Amazonia itself. These benefits led to the primary export of cassava beyond South America within the sixteenth century, and its range quickly expanded across tropical Africa and Asia. Today production takes place in countries reminiscent of Nigeria and Thailand far exceeds the production of South America's largest producer, Brazil. These successes raise optimism that cassava is usually a success environmentally friendly food source for populations worldwide.

While cassava will not be yet a household name within the United States, it’s well on its way. It has long flown under the radar in the shape of tapioca, a cassava starch utilized in puddings and boba tea. It also is available in the shape of on the shelves of the snack department Cassava chips and the baking process constituted of naturally gluten-free flour. Raw cassava can be on the rise, appearing under the names “yuca” and “cassava” in stores catering to Latin American, African and Asian populations.

Find a few of them and provides it a try. Supermarket cassava is totally secure and recipes abound. Cassava fritters, Cassava fries, Cassava cake … the probabilities of cassava are almost limitless.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply