Journalism is in a credibility crisis. 32% of Americans There are reports of “very high” or “fairly high” trust in reporting – a historic low.

Journalists generally assume that their lack of credibility is on account of the perceived political bias of their reporters and editors, so that they consider that the important thing to improving public trust is to eliminate any trace of political bias from their reporting.

This explains why editors repeatedly advocate for the retention of “objectivity“as a journalistic value and admonish Journalists for share their very own Opinions on social media.

The underlying assumption is easy: News organizations struggle to keep up public trust because journalists consistently give people reasons to distrust the individuals who bring them the news. Newsroom leaders appear to consider that the general public might be more more likely to trust their journalists—and maybe even pay for them—in the event that they perceive them as politically neutral, objective-thinking reporters.

But a study I recently published with journalism scholars Seth Lewis And Brent Cowley In Journalism, an educational publication, suggests that this mistrust stems from a very different problem.

Based on 34 Zoom interviews with adults representing a cross-section of age, political affiliation, socioeconomic status, and gender, we found that folks's distrust of journalism doesn’t stem from fear of ideological brainwashing. Rather, it stems from a belief that the news industry as an entire values profit over truth or public service.

The Americans we surveyed consider that news organizations report inaccurately not because they need to steer their audiences to support particular political ideologies, candidates, or causes, but just because they need to expand their audiences and thereby generate greater profits.

Mensent Photography/Getty Images

Commercial interests undermine trust

The business of journalism depends totally on the eye of the general public. News agencies generate profits not directly from this attention by making the most of the advertisements that accompany news stories – previously in print and on television, now increasingly digital. They also generate profits directly from this attention by charging the general public for subscriptions to their services.

Many news organizations pursue revenue models that mix each approaches, despite serious concerns concerning the likelihood that either approach results in financial stability.

Although news organizations depend on revenue for his or her survival, the occupation of journalism has long had a “Firewall” between its editorial decisions and business interests. One of the long-standing values of journalism is that journalists should report whatever they need without worrying concerning the financial impact on their news organization. NPR's ethics manual, for instance: States that “The purpose of our firewall is to limit the influence of our donors on our journalism.”

What does this appear to be in practice? It signifies that, under these principles, Washington Post journalists should feel encouraged to conduct investigative reporting on Amazon, although the newspaper is owned by Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos.

While the effectiveness of this firewall in the actual world anything but secureits existence as knowledgeable principle suggests that many working journalists take pride in following a story wherever it leads, whatever the financial impact on their company.

Yet despite the importance of this principle for journalists, the people we interviewed seemed unaware of its significance—indeed, its very existence.

Bias towards profits

The people we spoke to assumed that news organizations generate profits primarily through promoting, reasonably than through subscriptions. This led many to consider that news organizations are under pressure to focus on the biggest possible audience to be able to generate more promoting revenue.

Many of those surveyed subsequently described journalists as being in a relentless, never-ending battle for the general public’s attention in an incredibly crowded media landscape.

“If you don’t reach a certain number of views, you’re not making enough money,” said one in every of our interviewees, “and that doesn’t end well for the company.”

The people we spoke to mostly agreed that journalism is biased, and assumed that this bias is motivated by profit reasonably than strictly ideological reasons. Some see a convergence of those reasons.

“[Journalists] “We get money from various support groups that need to push a certain agenda, like George Soros,” said another interviewee. “It's about profits as an alternative of journalism and truth.”

Other interviewees were clear that some news organizations are primarily financially depending on their audiences in the shape of subscriptions, donations or memberships. Although these interviewees assessed the sources of revenue for news organizations otherwise than those that assumed that cash got here primarily from promoting, they nevertheless described a deep distrust of the news that resulted from concern concerning the business interests of the news industry.

“This is how they make their money,” one person said of subscriptions. “They want to seduce you with a different version of the news, which in my personal opinion is not entirely accurate. They make you pay for it and – hey presto – you're a sucker.”

Unfounded fears of bias

In light of those findings, journalists’ concerns about having to defend themselves against accusations of ideological bias seem unfounded.

Many news organizations followed Efforts at transparency as an overarching approach to gaining public trust, with the implicit aim of demonstrating that they do their work with integrity and free from ideological bias.

Since 2020, for instance, the New York Times has been conducting a “Behind the journalism” page describing how the paper’s reporters and editors approach every thing from using anonymous sources to confirming breaking crime news and their coverage of the war between Israel and Hamas. The Washington Post also began a “Behind the story“ page in 2022.

But these accounts don’t address the principal concern of the people we interviewed: the influence of greed on journalistic work.

David Livingston/Getty Images

Instead of worrying a lot concerning the perception of journalists' political bias, it’d make more sense for newsroom leaders to focus their energies on counteracting the perception of economic bias.

Perhaps a more practical demonstration of transparency can be to focus less on how journalists work and more on how the financial concerns of reports organizations are separated from the evaluation of journalists' work.

Cable news as a substitute

The people we interviewed also often appeared to confuse television news with other forms of reports production, comparable to print, digital and radio. And there may be ample evidence that television news executives do indeed appear to prioritise profits over journalistic integrity.

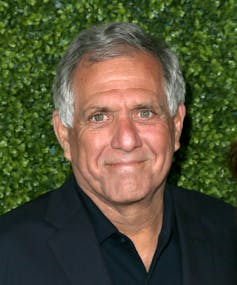

“It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” said CBS Chairman Leslie Moonves the large coverage of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump in 2016. “The money is rolling in.”

Against this background, discussions about improving trust in journalism could perhaps begin by acknowledging the extent to which public skepticism toward the media is justified – or not less than by distinguishing more clearly between various kinds of news production.

In short, individuals are skeptical of the news and distrust journalists. Not because they consider that journalists need to force them to vote in a certain way, but because they consider that journalists need to generate profits off of their attention.

For journalists to noticeably address the causes of public distrust of their work, they need to recognize the economic nature of that distrust and develop into aware of their role in maintaining it.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply