Charles Kingley was a widower and single father of 4 children living within the Northern Liberties neighborhood of Philadelphia in 1829. He worked in a brewery but struggled to supply for his youngest child, William, who was about five years old and nearly blind.

Barbra Sion, a 74-year-old woman from Southwark, was recorded by social employees as “aged, infirm, in the care of an adopted child.”

To stay of their homes and take care of their family members, each Philadelphians sought financial assistance from the Guardians of the Poor, the elected government officials who administered local welfare programs. But within the 1810s and 1820s, these pensions were got here under suspicion in PhiladelphiaDid families just like the Kingleys or the Sions really deserve support or were they simply pretending?

As a scholar of early American history Historian for Disability and as a disabled person, I’m very attentive to the discussions about disability from the founding of the United States to the current. While researching the on a regular basis experiences of disabled Philadelphians within the early nineteenth century, I discovered the records of the Guardian of the Poor within the Philadelphia City Archives.

In my research, published within the spring issue 2024 of Journal of the Early RepublicI examine how and why the Guardians of the Poor, together with other social reformers, began rationing health care and banning pensions.

Guardian of the Poor

At the start of the nineteenth century, Philadelphia, like most early American cities, had a diversified welfare state.

The Guardians of the Poor collected a poor tax from every household. They used this money to purchase on a regular basis goods resembling firewood, food and clothing for the poor and distributed weekly pensions to needy families.

They also supported public institutions resembling the Philadelphia Poorhousethat provided shelter and basic necessities to town’s poorest people. And they bought places within the Pennsylvania Hospitalwhere they referred poor people for medical care.

While the poorhouse and hospital were vital places of healing, many disabled households trusted the pension system. Pensioners could receive medical care at home from doctors employed by the Guardians of the Poor. With additional income, they might proceed to work and live independently.

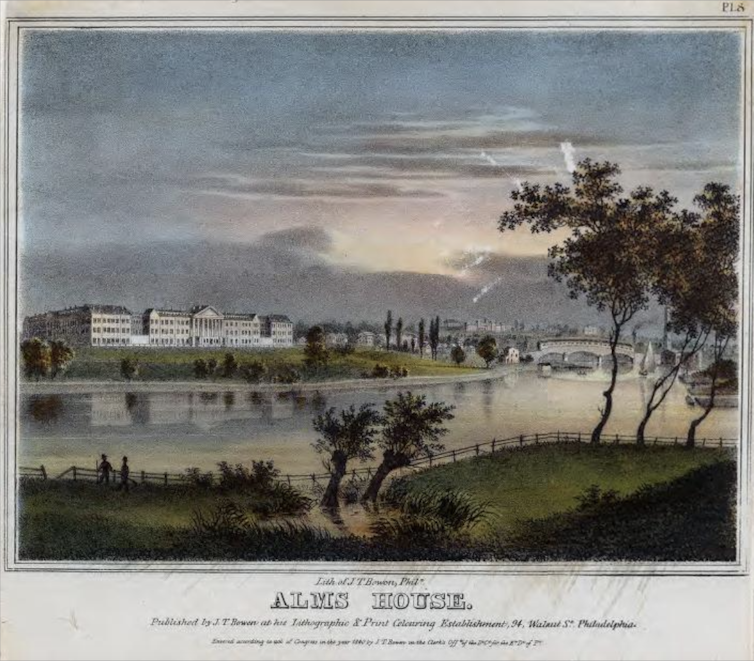

John T. Bowen/Library of Congress/World Digital Library

Increasing poverty, growing discontent

Like most cities on the East Coast within the early nineteenth century, Philadelphia was home to Thousands of immigrants and a growing free black communityThere were also increasing Unemployment and vagrancyDebts from the War of 1812 against Great Britain and inflation from the Panic of 1819.

As more people fell into poverty, more people turned to local social services for assistance.

Taxpayers, alternatively, complained concerning the rising costs of the welfare stateparticularly the pension system. Why should anyone work, they asked, if the federal government was just handing out money? Were people really unfit for work or were they simply deceiving the guardians of the poor? There was a pervasive feeling that fraudsters were emptying the coffers.

In 1817, a residents’ initiative called for the Pennsylvania Public Economic Development Corporation launched an investigation into the system. She sent a survey to charities and government officials asking, “What do the poor say is the cause of their poverty?”

The charities and officials reported: “In most cases, lack of jobs is given as the cause…[A]This may work temporarily, but the real causes are usually idleness, excess and disease.”

The Citizens' Committee's report concluded that “the colored people, the lower classes of Irish emigrants, the intemperate and the day laborers” were wasting taxpayers' money.

Pennsylvania Public Economic Development Corporation

While the committee at times pointed to gender pay gaps, high living costs and other real challenges, it focused totally on individual behaviour and private decisions. The authors found that poor people were careless with their money: they gambled, hired sex employees and drank themselves into poverty.

The report triggered a series of further investigations. In 1821, a state committee was established to take care of the Poor Lawsand in 1827 the Guardians of the Poor published the outcomes their very own investigation.

They all repeated the identical narrative: the incorrect people were profiting from welfare.

An enormous poorhouse

To treatment these social problems, the residents' committee proposed stopping pension payments and placing the poor in homes. Reformers argued It can be far cheaper to accommodate the poor together and supply them with food, clothing and shelter on a big scale.

In Philadelphia, this meant shifting taxes to the poor with the intention to Blockley Almshousea 3,000-bed facility that serves as PoorhouseOrphanage, hospital and workhouse on the west bank of the Schuylkill River – an area that was then on the Outskirts of townremoved from the families and communities of most residents.

In 1902, the ability was renamed Philadelphia General Hospital. It was closed in 1977 and shortly razed. Today, the space houses various facilities owned by the PGH Development Corp.

Like the manuscript collections of the Guardians of the Poor in Philadelphia City Archives To be clear, Blockley Almshouse has hired medical professionals to look at those admitted and supposedly distinguish profit fraudsters from those that deserve care.

Sick and injured people were taken to the hospital wards, where they met doctors and medical students. Students on the University of Pennsylvania accomplished their clinical rounds within the poorhouse, where they performed operations, prepared medications, and learned diagnose patients.

Both disabled and able-bodied poor were sent to the workhouse, where they’d to perform tasks resembling Plucking tow – where ropes are separated into individual fibres – Winding yarn, sewing clothes or making shoesWhatever they produced was sold in local markets to finance the ability.

Reformers suspected that the majority people would find the conditions within the workhouse so appalling that they would go away and seek work in town as an alternative.

African American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

The so-called fraudsters

It is difficult to assume what the workhouse could offer families just like the Kingleys or the Sions, just two of the 656 families listed within the register of relief recipients kept by the Guardians of the Poor for 1829.

When I transcribed the register, I discovered that every one 656 households on the pension roll were home to single parents, elderly people, individuals with disabilities, or some combination of those people. Most had lived in town for many years.

Ironically has never made a profit. Philadelphians continued to fund the ability through tax revenues, and it never broke even.

The real cost, after all, was borne by the individuals who were forcibly placed in homes, divided into different wards in line with gender and health status, and separated from their families by the vastness of the river.

Many lived in abject poverty to flee the institution. In 1830, Mathew Carey, an economist and public figure in Philadelphiacomplained that a whole bunch of Philadelphians “have gradually fallen into the worst distress and poverty – that honorable men would shudder at the sight of the inmates of a poorhouse, and that they would indeed rather die than go there” deserved pension support.

Changing the welfare laws – taking away pensions and funding institutions as an alternative – acted like a net to catch and punish economically dependent people. The welfare reformers could have set their sights on employers, businesses, rent costs or other systemic causes of poverty. Instead, they focused on alleged fraudsters who in point of fact didn’t exist.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply