Five hundred years ago, in a mountain-lined fjord in southeast Alaska, Tlingit hunters armed with bone-tipped harpoons navigated their canoes through drifting ice and pursued seals near the Sít Tlein (Hubbard) Glacier. They should have looked nervously up on the looming, jagged glacier wall, aware that ice masses could crash down and endanger the boats – and their lives. As they approached, they asked the seals to present themselves to the people as food and spoke to the spirit of Sít Tlein to release the animals from his care.

The Tlingit elders within the Alaska Indian village of Yakutat today describe the daring quest of their ancestors for Sealsor “Tsaa”, and folks’s respect for the spirits of the mountains, glaciers, ocean and animals of their subarctic world.

Long ago, it is alleged, migrating clans of the Eyak, Ahtna and Tlingit tribes settled in Yakutat Fjord because the glacier retreated, and over time moved their hunting camps to remain near the ice floe. colony where animals give birth each spring. Clan leaders controlled the hunt to avoid premature harvest, overhunting or waste, which is consistent with indigenous values of respect and balance between humans and nature.

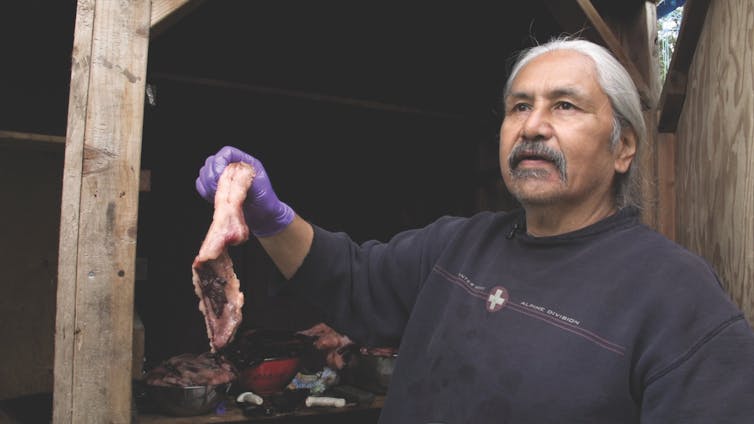

Today, the 300 Tlingit people of Yakutat proceed this lifestyle in a contemporary form, catching over 100 different species of fish, birds, marine mammals, land game and plants for their very own consumption. Seals are crucialtheir wealthy meat and bacon are prepared in line with traditional recipes and eaten at every day meals and Memorial Potlatch Celebrations.

© Smithsonian Institution

But the community is facing a crisis: the dramatic decline of the seal population within the Gulf of Alaska attributable to business hunting within the mid-Twentieth century and the dearth of recovery attributable to warming oceans. To protect the seals and their lifestyle, residents are turning to traditional ecological knowledge and time-honored conservation practices.

We are an Arctic archaeologist which examines human interactions with the marine ecosystem and a Tlingit tribal historian the Yakut Kwáashk'i Kwáan clan. We are two of the leaders of a project that has investigated the historical roots of the situation.

Our collaborative research, involving archaeologists, environmental scientists, Tlingit elders, and the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe, was published as a book “LaaXaayík, Near the Glacier: Indigenous History and Ecology at Yakutat Fiord, Alaska.” In it, we detail the changing lifestyle of an indigenous people and their evolving relationship with their glacial environment over the past 1,000 years, combining indigenous people’s knowledge of history and ecology with scientific methods and data.

Ancestral sealing

According to oral tradition, the village of Tlákw.aan (“old town”) was built on an island within the Yakutat Fjord by the Gine.X Kwáan, an Ahtna clan from the Copper River who migrated over the mountains, married the Eyak and traded ceremonial copper shields for land of their latest territory. They subsisted on the abundant resources of the fiord and hunted on the seal colony near the receding glacier, then positioned a number of miles to the north.

Today Tlákw.aan is a cluster of clan house foundations in a quiet forest clearing and our excavations there in 2014 aimed to learn more in regards to the lives of the inhabitants and their use of seals before western contact.

Collection accessed courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum; artifact scans © Smithsonian Institution.

Radiocarbon dating shows that Tlákw.aan was built around 1450 AD. Coordination of oral reports with reconstruction by geologists the position of the glacier at the moment. Artifacts confirm the identity of the inhabitants as Ahtna and Eyak. Seal finds found at the location include harpoon points, stone oil lamps, skin scrapers and copper scraping knives. Seal bones are common, with greater than half coming from pups captured on the colony.

The site reflects Aboriginal conditions – a big seal population, dependence on seals for meat, oil and fur, and sustainable hunting within the glacier colony.

Effects of business sealing

The purchase of Alaska from Russia by the United States in 1867 interrupted the standard seal hunt in Yakutat. To meet the increasing global demand for seal skins and oil, the Alaska Commercial Company supplied Alaska’s natives with guns and recruited them to kill hundreds of seals.

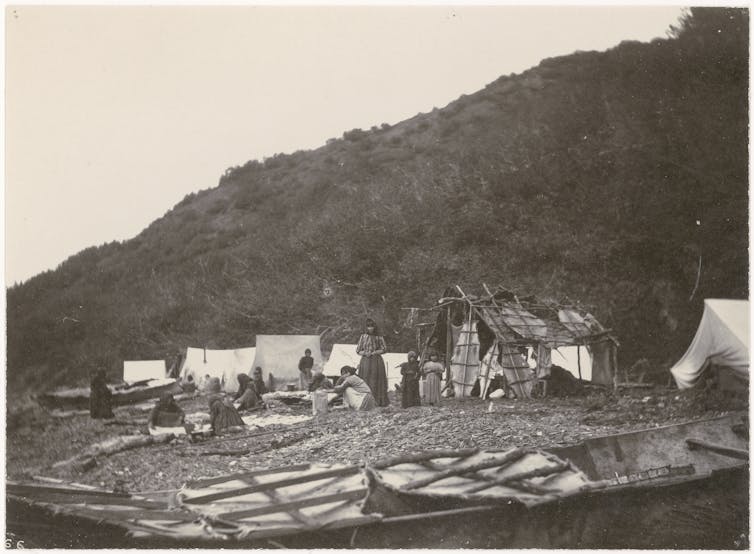

Yakutat was a crucial hunting ground for the brand new industry from about 1870 to 1915, and every spring the complete community moved from their winter village to hunting camps near the glacier. Men shot seals and girls prepared the skins, smoked the meat, and made oil from the blubber. In the autumn the lads paddled in seaworthy canoes loaded with seal products for trade to the Alaska Commercial Company's base in Prince William Sound.

Edward Curtis, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P10970)

We compared historical data and reports of the elders from this era with archaeological finds from Keik'uliyáa, the most important camp. The scale of the operation is clear in photographs from 1899, which show long rows of canvas tents, smokehouses, sealskins drying on racks, stranded hunting canoes, and girls searching piles of seal carcasses. In the rock outlines of the tents we found glass beads, rifle cartridges, nails, glass containers, and other trade goods that reflect the changing culture of the community and its incorporation into the capitalist market system.

© Smithsonian Institution

Commercial hunting overwhelmed the seals' ability to breed, causing the population to collapse within the Twenties. This cycle repeated itself within the Sixties, when world prices for fur soared and tons of of hundreds of seals within the Gulf of Alaska were killed by local hunters, exceeding sustainable yields. Seal population declined by 80-90%.

Although business sealing began in 1972 with the Marine Mammal Protection Actthe seals have never recovered. The days when the ice floes were “black with seals,” as Yakutat elder George Ramos Sr. recalled, are over, perhaps ceaselessly. The warming of the oceans attributable to global climate change and an unfavorable cycle of Pacific Decadal Oscillation has led to a decline in fish stocks which can be vital for the seals, thereby clouding their prospects of a return.

© Smithsonian Institution

Caring for seals and the community

In response, the Yakutat indigenous people modified their weight loss plan and severely restricted hunting. In 2015, they killed 345 seals – about one per person – in comparison with 640 in 1996. Hunting has now grow to be almost non-existent within the ice floe breeding grounds, allowing the seals to lift their young undisturbed.

The community is working with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Alaska Native Harbor Seal Commission to Monitoring and co-management of the herdby contributing their indigenous expertise on seal behaviour and ecology. They have also been actively involved in efforts to Protect the seal colony from disturbance by cruise ships.

The Yakutat persons are recommitting themselves to the traditional principles of responsible care and spiritual respect for seals, searching for to make sure the survival of the species and the continuation of the life-sustaining indigenous tradition of seal hunting.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply