K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil knew his story.

For eleven generations, the dynasty of the Mayan ruler Copan had ruled, a city-state near the present-day border between Honduras and Guatemala. From the fifth century AD to the seventh century AD, scribes painted his ancestral family trees in manuscripts and carved them into stone monuments throughout the town.

Around 650, a special piece of architectural history seems to have caught his eye.

Centuries earlier, village masons built special structures for public sun-viewing ceremonies—ceremonies timed to coincide with the solstice, similar to the one that can happen on June 20, 2024. The construction of such architectural complexes, which archaeologists call “E-groups,” had largely gone out of fashion by K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil's time.

But to appreciate his ambitious plans for his city, he seems to have found inspiration in these astronomical public spaces, as I even have seen in my research on ancient Mayan astronomy in hieroglyphs.

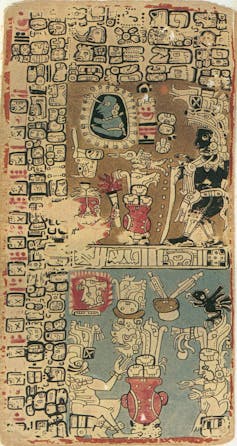

Andrew Dalby/Wikimedia Commons

The innovations of K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil are a reminder that science changes through discoveries or inventions – but occasionally also for private or political reasons, especially in precedent days.

Looking on the horizon

E-groups were first inbuilt the Maya region as early as 1000 BC. The site of Ceibal on the banks of the Pasión River in central Guatemala is one such example. There, the inhabitants built a protracted, plastered platform borders the eastern edge of a giant plaza. Three buildings were arranged along a north-south axis on this platform, with roofs high enough to protrude above the rainforest cover.

In the middle of the square, west of the platform, they built a radially symmetrical pyramid. From there, observers could watch the sunrise behind and between the structures on the platform all year long.

At one level, the earliest E-Group complexes served very practical purposes. In Preclassic villages where these complexes were found, similar to Ceibal, several hundred to several thousand people made their living from “milpa” or “slash-and-burn” agriculture. still maintained in pueblos throughout Mesoamerica today. Farmers cut down scrub vegetation after which burn it to fertilize the soil. This requires careful attention to the rainy season, which in precedent days was tracked by the position of the rising sun on the horizon.

However, most sites within the Classic Maya heartland lie in flat, forested landscapes with few notable features on the horizon. To the viewer standing on top of a tall pyramid, all that’s striking is a green sea of flower crowns.

Wirestock/iStock via Getty Images Plus

By interrupting the horizon, the eastern structures of the E-Group complexes might be used to mark solar extremes. The sunrise behind the northernmost structure of the eastern platform might be observed on the summer solstice. The sunrise behind the southernmost structure marked the winter solstice. The equinoxes might be marked halfway between them when the sun rose due east.

Scientists are still discussing Key aspects of those complexesbut their religious significance is well documented. Finds of finely crafted jade and ritual ceramics reflect a cosmology based on the 4 cardinal directionswhich can have been coordinated with this 12 months's E-Group division.

Dwindling knowledge

However, the residents of K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil were probably less attuned to direct remark of the sky than their ancestors.

By the seventh century, the political organization of the Maya had modified considerably. Copan now had 25,000 inhabitants.and agricultural technologies also modified to maintain pace. The cities of the classical period practiced several types of intensive agriculture which relied on sophisticated water management strategies and mitigated the necessity to meticulously follow the sun's horizon movement.

E-Group complexes were still installed within the classical era, but were now not aligned with the sunrise and served more political or stylistic purposes than the representation of celestial views.

Such a development, I believe, remains to be relevant today. People listen to the changing seasons and know when the summer solstice occurs because of a calendar app on their phone. But they probably don't remember the science behind it: how the lean of the Earth and its path across the Sun make it appear as if the Sun itself is moving north or south on the eastern horizon.

United through ritual

By the mid-seventh century, K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil had developed ambitious plans for his city – and astronomy offered a strategy to help realize those plans.

He is thought today for his extravagant burial chamberan example of the success he eventually achieved. This tomb is situated in the center of an impressive constructing, in front of which the “Hieroglyphic Staircase“”: a record of the history of his dynasty, which is probably the most extensive single inscriptions in ancient history.

Peter Andersen/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil looked for tactics to remodel Copan right into a regional power and sought alliances beyond the local nobility. He turned to the encircling villages.

Over the last century, several scholars, including myself, have studied the astronomical component of his plan. It appears that K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil commissioned a series of stone monuments or “stelae” to be erected throughout the city and within the foothills of the Copan Valley, and followed the sun on the horizon.

Like the E-Group complexes, these monuments involved the general public in observing the sun. Viewed together, the stelae formed a countdown to a very important calendrical event orchestrated by the sun.

In the Twenties, archaeologist Sylvanus Morley discovered that from Stela 12 within the east of the town, one could watch the sunset behind Stela 10 on a hill to the west twice a 12 months. Half a century later Archaeoastronomer Anthony Aveni realized that these two sunsets defined 20-day intervals relative to the equinoxes and the zenith passage of the sun, when the shadows of vertical objects disappear. Twenty days is a very important interval within the Mayan calendar and corresponds to the length of a “month” within the solar 12 months.

My own research showed that the dates on several steles also commemorate a few of these 20-day interval events. Moreover, all of them result in a 20-year event called the “Katun End.”

Daderot/Wikimedia Commons, From

K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil celebrated this katun end and set in motion his plans for regional hegemony in Quirigua. a growing, influential city about 30 miles away. A round altar there bears a picture of him commemorating his arrival. The hieroglyphic text tells us that K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil “danced” at Quirigua, thus sealing an alliance between the 2 cities.

In other words, K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil's “sun steles” did greater than just track the sun. The monuments brought communities together to witness astronomical events and thus share cultural and spiritual experiences across generations.

Collectively appreciating the natural cycles that make life on Earth possible is something that, I hope, won’t ever exit of fashion.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply