Museums often rejoice latest acquisitions, especially of rare or historic specimens. In April 2024, scientists from the Natural History Museum of Jamaica and the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, took delivery of a really rare and historic specimen: a 16-inch-long lizard called the Jamaican giant galli wasp (Celestial West)It was previously kept within the Hunterian Museum on the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

“'Celeste' is home!” announced a Jamaican news agencyreferring to the nickname given by scientists to the reptile, which they believed to be female.

Jane Barlow/PA Images via Getty Images

Why should a preserved lizard that’s about 170 years old cause a lot excitement? Celeste was collected within the 1850s and represents a species that was endemic to Jamaica but is now considered threatened with extinction and possibly extinctScientists in Jamaica who’ve never seen or touched considered one of these lizards, are excited to have one to check.

As a scholar of Jamaican Landscape Stories who’re desirous about Environmental justicewe imagine this repatriation illustrates vital truths about colonialism and its legacy. Celeste’s 170-year stay in a Scottish university collection speaks to uneasy connections between Colonialism and natural history.

Sample collection worldwide

As early because the seventeenth century, officials, doctors, naturalists and amateurs from Europe traveled the colonized worldcollected local plants and animals, in addition to artistic and cultural objects made by individuals who lived in these areas. Many objects they brought back with them, in addition to items officially archived during natural history expeditions, are actually kept in European libraries and museums.

In recent a long time, museums have begun repatriate some objects to their native land. As loans and full repatriations change into more common, natural history collections are concerned with the origins of lots of their holdings, including plants and animals.

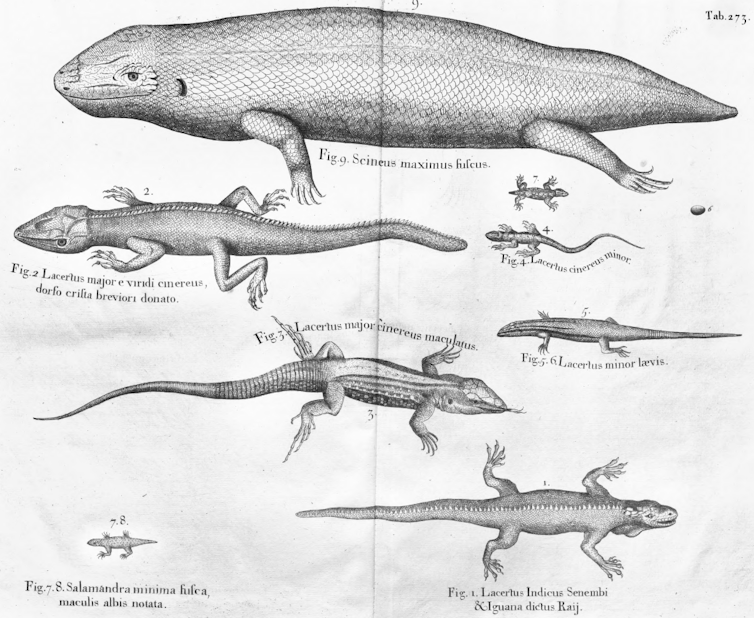

The field of natural history has benefited from the variety of geographies and ecologies that formed European empires. For example, “The civil and natural history of Jamaica“” by Patrick Browne, published in 1755, was the first text in English to describe the Carl LinnaeusThe book shows how vital advances in natural history, botany and biology were based on field research conducted far beyond the borders of Europe.

Colonial sites where scientific studies were carried out received little attention in natural history reports. The research and collection of samples relied on the knowledge and the labor of enslaved individuals, who acted as field assistants and guides – but there’s little details about their roles within the historical records.

Expeditions and experiments with plants, especially those of economic or medical valuecreated global botanical networks. Today there are organizations like Royal Botanic Gardens Kew in England and the New York Botanical Garden We proceed to depend on the knowledge and collections from tropical botanical gardens from the colonial era in places just like the Caribbean islands of St. Vincent and Jamaica.

Species extinction in Jamaica

In Jamaica there was a direct relationship between geological exploration and the plantation system. The first geological surveys of Jamaica were carried out by naturalists. Sir Henry De la Bechethe son of a Jamaican plantation owner and first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain.

British physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane's Extensive holdings of books, manuscripts and specimens became the founding collection of the British Museum. Sloane collected and documented objects through an expanding British Empire while serving as a physician to colonial officials. His collections include greater than 1,500 plant samples from Jamaicawhich he acquired there from 1687 to 1689.

Biodiversity Heritage Library, CC BY-ND

After England officially took possession of Jamaica in 1670, it founded Monoculture production of sugar cane across the island. Extensive deforestation, damage to local ecosystems and the consumption of exotic foods took a heavy toll. Some of the plant and animal specimens recovered by collectors and exported abroad would be the only ones still in existence today.

The colonizers also introduced harmful species, reminiscent of the Indian mongoose (H. edwardsii), which was delivered to Jamaica to hunt rats on sugar cane plantations. Mongooses are omnivores that feed on a wide range of foods, including mice, lizards, snakes, beetles, birds, and eggs.

The Indian mongoose quickly became a serious threat to quite a few species, including the Jamaican giant gall wasp. To at the present time, it stays a very important opponent within the fight to stabilize the population of the endangered Jamaican iguana.

JM Garg/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Restoring an island’s ecology

Celeste is the primary natural history specimen to be officially returned to the Caribbean, but not the primary. In 2009, the British Museum announced the Anthony Robinson Volumes to the Institute of Jamaica, which had loaned them in 1920 to help within the preparation of a book on Jamaican plants. These papers were unpublished notes and illustrations by a naturalist who died in Jamaica in 1768 after observing and collecting wildlife for about 20 years.

Subsequently, in 2016, Royal Holloway College, University of London, donated an estimated 10,000 artworks from the Second World War and the pre-independence period. Aerial photographs of the British colonies within the West Indies to the University of the West Indies. These photographs will be useful in studying changes within the natural landscape or rural land cover as a result of the expansion or abandonment of agricultural operations. They also provide a frame of reference for tracking modern urban expansion.

Returning samples, artifacts, and other materials is a very important method to show respect to the societies and cultures that produced them. Plant and animal specimens may contribute to ecological restoration.

The classification of the Jamaican giant gall wasp as possibly extinct within the wild reflects the optimism of the virtually unbelievable rediscovery of the Jamaican Iguana (Cyclura collei). Before 1990, this species was regarded as extinct, but then scientists discovered a remaining population within the Hellshire Hills of the island. This discovery gives hope for other species which might be considered extinct but may survive in small, isolated areas.

Rob Buhlman/Flickr, From

Finally, Celeste's return to Jamaica shows how the repatriation of fabric artifacts can function a part of a broader technique of reparations for colonialism. Celeste will not be an isolated case. We have noted that the American Museum of Natural History in New York City is Holotype from Xenothrix mcgregoridescribed as a Jamaican monkey. The skull of this monkey was present in a cave in Trelawny in 1920. There are also fossil specimens of Oryzomys antillarumthe Jamaican rice rat, within the vertebrate paleontology collection of the University of Florida and one within the Natural History Museum of London, collected by PH Gosse in 1845.

Although Celeste’s return is essentially symbolic, it recognizes how colonialism enabled multiple types of plunder with lasting consequences and demonstrates the necessity for decolonization in Natural HistoryInstead of remaining within the camp, Celeste has returned to Jamaica to change into a central piece of Jamaican environmental history.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply