Some white people still appear to be tormented by an odd wish: “I wish I knew what it was like to be black.”

This desire is different from the will to embody the coolness of being black – to emulate style, imitate music, and parrot slang.

This is a supposedly racist, imaginative desire that desires not only the rhythm of black life, but in addition its blues.

Although he doesn't need to admit itThe Canadian-American journalist Sam Forster is certainly one of these white people.

Three years after the allegations against George Floyd scream “Mommy” so desperate that it brought a rustic out of quarantine, Forster donned an artificial afro wig and brown contact lenses, dyed his eyebrows and smeared his face with Maybelline liquid foundation within the shade “Mocha” purchased at CVS. Although Forster doesn’t have a “Cinema quality” Transformation, he was, in his words, “Believably black.”

He dared to undertake a racial experiment that nobody had asked for. In his recently published memoirs he wrote about it: “Seven Shoulders: Taxonomizing Racism in Modern America.”

For two weeks in September 2023, Forster pretended to hitchhike on the shoulder of a freeway in seven different U.S. cities: Nashville, Tennessee; Atlanta; Birmingham, Alabama; Los Angeles; Las Vegas; Chicago, and Detroit. On the primary day in the town, he stood on the side of the road as his white self, waiting for somebody to stop and provides him a ride. On the second day, he stuck his thumb on the identical shoulder, but this time with what I’d describe as a “mocha face.”

Since September is hot, he set a two-hour limit for his experiments. During his seven white days, he was offered seven rides, but he didn’t take them. On seven subsequent black days, he was offered one ride, but he didn’t take it. He speculated that this present day was a coincidence.

Forster will not be the primary white man to take center stage within the discussion about American racism by pretending to be black.

His desire reflects that of the white people described in my 2017 book:Black for a day: White fantasies about race and empathy.” The book tells the story of what I call “empathetic racial imitation,” by which whites indulge their fantasies of being black under the guise of empathy with the black situation.

In my view, these efforts are futile. They ultimately reinforce stereotypes, fail to deal with systemic racism, and convey a false sense of racist authority.

Undercover within the South

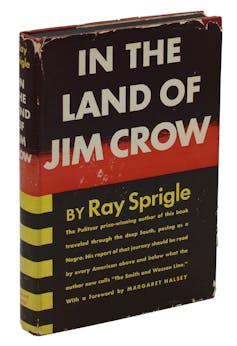

Burnside Rare Books/eBay

The genealogy begins within the late Nineteen Forties with Pulitzer Prize winner and journalist Ray Sprigle.

Sprigle, a white reporter on the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, decided to experience postwar racism by “becoming” black. After trying in vain to make his skin darker than simply brown, Sprigle shaved his head, donned enormous glasses, and traded his trademark 10-gallon hat for a plain cap. For 4 weeks starting in May 1948, Sprigle navigated the Jim Crow South as a light-skinned black man named James Rayel Crawford.

Sprigle documented dilapidated sharecroppers' shacks, racially segregated schools, and ladies widowed by lynching. What he saw – but didn’t experience – was incorporated into his 21-part series of articles for the front page of the Post-Gazette. He followed the series in 1949 with a widely panned autobiography: “In the land of Jim Crow.”

Sprigle never won this second Pulitzer Prize.

Cosplay as a black man

Sprigle’s more famous successor, John Howard Griffin, published his memoirs: “Black like me”, in 1961.

Like Sprigle, Griffin explored the South as a short lived black man, darkening his skin with pills that Vitiligoa skin condition that causes patchy lack of pigment. He also used dyes to even out his skin tone and hung out under a tanning lamp.

During his weeks as “Joseph Franklin,” Griffin encountered racism on several occasions: White thugs chased him, bus drivers refused to let him get off to pee, branch managers refused to let him work, white men who didn’t come out aggressively approached him, and otherwise nice-looking white people bombarded him with what Griffin called the “Hate-Look.” When Griffin became white again and news of his racial experiment got here to light, his white neighbors from his hometown of Mansfield, Texas, left him hanging in effigy.

Griffin was praised for his work as an icon of empathy. Unlike Sprigle, he had experienced racist incidents himself, and Griffin showed skeptical white readers what they didn’t need to consider: racism was real. The book became a bestseller and a movieand remains to be a part of the varsity curriculum – albeit on the expense of African-American literature, I’d add.

Christina Saint Marche/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Griffin’s significance for this genealogy extends beyond the center school students reading “Black Like Me” to his successor and mentee, Grace Halsell.

Halsell, a contract journalist and former editor for the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson, decided to “become” a black woman – first in Harlem in New York City after which in Mississippi.

Without consulting a black woman before frying herself to caramel within the tropical sun and getting medication for vitiligo from Griffin's doctors, Halsell initially planned to “be black” for a yr. But after she claimed someone tried to sexually assault her while she was working as a black domestic helper, Halsell ended her time as a black woman early.

Although her experiment only lasted six months, she still claimed to be someone who could authentically represent her.darker sistersIn her 1969 memoirs she states: “Soul sister.”

“Racial change” on the turn of the century

Forster writes that his 2024 memoir is the “fourth act” – after Sprigle, Griffin and Halsell – of what he calls “journalistic blackface.”

However, as he himself claims, he will not be “the first person in over half a century to seriously overcome racial segregation.”

In a 174-page book, which he himself describes as “Gonzo“With only 17 citations, Forster has not done his homework.

In 1994, Joshua Solomon, a white college student, medically dyed his skin to change into a black man after reading Black Like Me. His originally planned month-long experiment in Georgia lasted only just a few days. Nevertheless, he described his experience in an article for The Washington Post and got a gig at “The Oprah Winfrey Show.”

Then, in 2006, FX released: “Black-and-white.”, a six-part reality TV series promoted because the “ultimate racial experiment”.

Two families – one white, one black – “swapped” their races to present versions of one another while living together in Los Angeles. While the makeup team won a Primetime Emmy AwardThe families said goodbye with seething resentment as a substitute of understanding.

A master class of white arrogance

Believing it might distract from the outcomes of his experiment, Forster refuses to indicate readers his mocha face.

Even after being confronted with evidence that forced him to query the appropriateness of his project, similar to the many articles condemning “the wearing of makeup to imitate the appearance of a black person,” he insists his insights into American racism justify his methods and distinguish them from the damaging legacies of blackface. As he stands on the side of the road, sun and sweat eroding the care he put into painting his face, Forster concludes that racism might be divided into two broad taxonomies: institutional and interpersonal.

The former, in his opinion, is “actually dead,” and the latter is normally perceived as a “shoulder,” similar to the subtle refusal to select up a hitchhiker with a mocha-colored face.

Forster's Amazon book description praises “Seven Shoulders” as “the most important book on race relations in America ever written.”

It is indeed a master class – but one in regards to the arrogance of white assumptions about blackness.

To think that one can understand the variety of black identity through a short lived costume trivializes the lifelong trauma of racism. It turns the complexity of black life right into a trick.

Whether it's Forster's premise that black individuals are incapable of testifying about their very own experiences, his questionable quotes, the hubris of his caricature, or the vitriol with which he speaks in regards to the Black Lives Matter movement, Forster is a crucial reminder that liberation can’t be bought at a pharmacy.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply