Although Frederick Douglass Although he’s the best-known abolitionist to go to Ireland within the many years before the American Civil War, he was not the just one.

In addition, as much as 30 black abolitionists and activists traveled to Ireland between 1790 and 1860. Olaudah Equiano was one among them. Equiano was born in Africa and kidnapped on the age of about 10. However, he later bought his freedom, wrote a best-selling autobiography and arrived in 1791 as a guest of the United Irishmen, a gaggle of radical nationalists.

Another was Sarah Parker Remondwho got here to Ireland in 1859 and stayed with the identical family that had hosted Douglass 14 years earlier. After experiencing equality for the primary time, she couldn’t bear to return to America.

Instead, she accomplished her studies at a school in London and moved to Italy, where she trained as a health care provider. Both Equiano and Parker Remond worked closely with Irish abolitionists.

Even before Douglass arrived in Ireland in 1845, he was aware of the wealthy tradition of Irish men and ladies involved within the transatlantic movement to finish the American slavery system.

In particular, he was an admirer of the Irish nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell. A vocal critic of slaveryO'Connell played a crucial role in finish it within the British Empire in 1833.

The Making of an Abolitionist

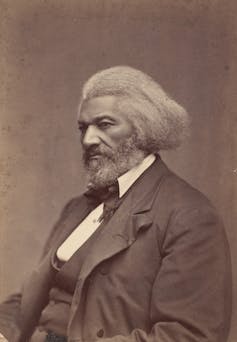

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born a slave in Maryland in 1818 and met his enslaved mother only a couple of times before she died. His father was widely believed to be the white owner of the plantation.

At the age of 20, Frederick fled to New York, where he modified his last name to Douglass.

Although he could have continued on to Canada, where he would have been secure, he selected to remain within the United States and work for the abolitionists. Although Douglass had no formal education, he proved to be a superb orator who had experienced slavery firsthand.

Douglass' fundamental motivation for travelling to Great Britain in August 1845 was to avoid being enslaved again. Seven years earlier, Douglass had declared himself free. However, under American law, he was still considered a “runaway slave” and will subsequently be caught at any time.

At the age of 27, due to his lectures, he was American Anti-Slavery Society and the success of his autobiography, which he published in May 1845.

Obviously he was a thorn within the side of slavery and its supporters.

The 12 months before his visit to Ireland, Douglass wrote:

“The true and only reliable movement for the abolition of slavery in this country and throughout the world is a great moral and religious movement. Its object is to enlighten the public, to quicken and enlighten the dead conscience of the nation, and to make them feel the gross injustice, fraud, wrong, and inhumanity of the enslavement of their fellow men.”

The fight in Ireland

Douglass was reluctant to go away America because he was married and the daddy of 4 young children.

Two days after his arrival within the port of Liverpool, Douglass travelled to Ireland, where a number one Irish abolitionist, Richard Webbhad offered to reprint Douglass's autobiography to offer him with much-needed income. Douglass had only intended to spend a couple of days in Dublin, but after the nice and cozy welcome he received, he ended up staying for 4 months.

During this time he gave nearly 50 lectures across the country. Despite his busy schedule, he described these months because the “happiest“ Period of his life:

“I am living a new life. The cordial and generous co-operation which I have received from the friends of my despised race… and the total absence of anything which appeared to be prejudice against me on account of the color of my skin – is in such strong contrast to my long and bitter experience in the United States, that I look upon the transition with wonder and amazement.”

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Part of Douglass' transition was based on the political approach of the Irish leader O'Connell and Belief in universal human rights:

“I am a friend of liberty in every climate, every class, and every color. My sympathy for suffering is not confined to the narrow confines of my own green island. No – it extends to every corner of the earth. My heart is abroad, and wherever the poor need to be helped or the slaves to be freed, there my spirit is at home, and I am happy to live there.”

O'Connell had won political rights for Catholicswho were traditionally regarded by the British establishment as second-class residents in Ireland. The comparison didn’t escape Douglass, who a letter from 1846 to the well-known American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison:

“I see much here that reminds me of my former condition, and I confess I should be ashamed to raise my voice against American slavery, but I know that the cause of humanity all over the world is one. He who really and truly sympathizes with the American slaves cannot arm his heart against the suffering of others; and he who thinks himself an abolitionist, but cannot understand the wrongs of others, has yet to find a true basis for his opposition to slavery.”

Return to America

In January 1846, Douglass left Ireland to lecture in Scotland and England. During his stay, he became homesick and longed to see his family again.

A gaggle of Irish and British women offered an answer. They raised the cash and accomplished the legal process to purchase Douglass's release.

Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Douglass returned to America as a free man in April 1847. But his latest status didn’t protect him from prejudice and racial discrimination.

Five years after his return home, Douglass delivered one among his the sharpest attacks on American slavery:

“What does the Fourth of July mean to the American slave? I answer: a day which reveals to him, more than any other day of the year, the gross injustice and cruelty of which he is constantly the victim. To him, your celebration is a farce.”

The long arc of history

In the years following the tip of the American Civil War, Douglass' influence as a global advocate for human rights continued to grow.

In 1887 he visited Ireland again, this time as an American citizen, holding a passport and being allowed to cross the Atlantic in a first-class cabin.

Douglass explained that the explanation for the trip was “to look into the faces of the people who had been kind to me 40 years ago.”

Sadly, most of them were dead.

During this visit, Douglass announced his support for Irish nationalists and their long struggle for independence.

Back home, Douglass continued the fight against “the hidden practices of men who have not yet given up the idea of dominion and domination over their fellow men.”

Douglass believed that further resistance was vital and quoted three words he had learned from O'Connell in Dublin in 1845: “Agitate, agitate, agitate.”

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply