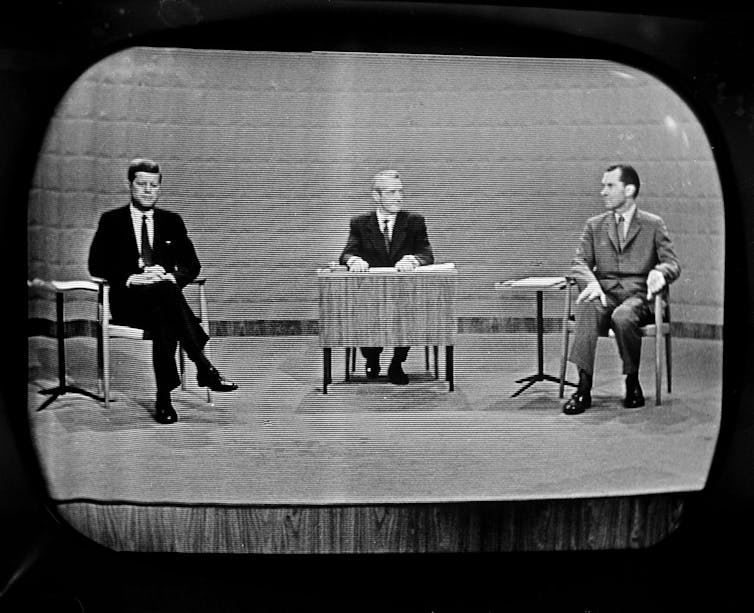

In the run-up to the controversy between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in End of June 2024 has brought memories concerning the first televised presidential debate – and the way Vice President Richard Nixon's sweaty, worn-out appearance on that autumn evening in 1960 paved the best way for the tanned and telegenic Senator John F. Kennedy to enter the White House.

At least, that is the common opinion concerning the Kennedy-Nixon debate of September 26, 1960: Image won, Kennedy was rewarded and Nixon was punished.

“Kennedy won the election by a narrow margin, although most people believe he would never have had a chance without that first debate,” Time magazine said. declared in 2016when he lists the most important missteps in political debates. “It seems that Nixon's fatal mistake was that he failed to recognize the power of the visual image.”

Or as Max Frankel, then editor-in-chief of the New York Times, wrote sarcastically several months After Nixon's death in 1994, “Nixon lost a televised debate and the presidency to John F. Kennedy in 1960 because he didn't follow the rules.”

Nixon could have been sweating under the new studio lights, but few pundits and analysts focused their comments on the vice chairman's appearance on the time. In a telling example of the fickleness of judgments within the moment, many pundits and analysts thought each candidates appeared nervous and unsure. Some of them said Nixon, still recovering from the consequences of a infected knee who had admitted him to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center at the tip of August 1960, had the upper hand within the confrontation.

At the time, the prevailing opinion was that this debate had not made any decision concerning the 1960 presidential election campaign.

Related Press

The debate as a draw

What is commonly told to the general public today about this primary debate of its kindwhich took place without an audience in a Chicago television studio, doesn’t quite match the reactions and perceptions circulating on the time. As the aftermath of the controversy made clear, initial assessments could be fleeting and result in dramatic revisions.

I actually have examined quite a few newspaper articles, editorials and commentaries written immediately after the controversy to organize a chapter for “Doing it wrong”, my 2017 book about Media-driven myths. I discovered that there was no consensus amongst newspaper columnists and editorial writers about Nixon's performance. Not everyone thought Nixon's performance was terrible or necessarily liked Kennedy.

Two days after the controversy, the Washington Post stated in an editorial: “Of the two performances, Mr. Nixon's was probably the smoother. He is an accomplished debater with professional elegance, and he managed to convey the slightly condescending impression of a master teaching his pupil.”

The moderator of the controversy, Howard K. Smith of ABC News, was later quoted as saying that he thought Nixon was “slightly better” than Kennedy.

Saul Petta well known columnist for the Associated Press, praised Nixon's radiant warmth. “In terms of popular approval, both before and during the debate,” Pett wrote in an article published the following day, “my scorecard showed Nixon slightly ahead, at least 8 to 1. … He smiled more often and more broadly, especially at the beginning and end of remarks. Kennedy only occasionally allowed himself the luxury of a quarter smile.”

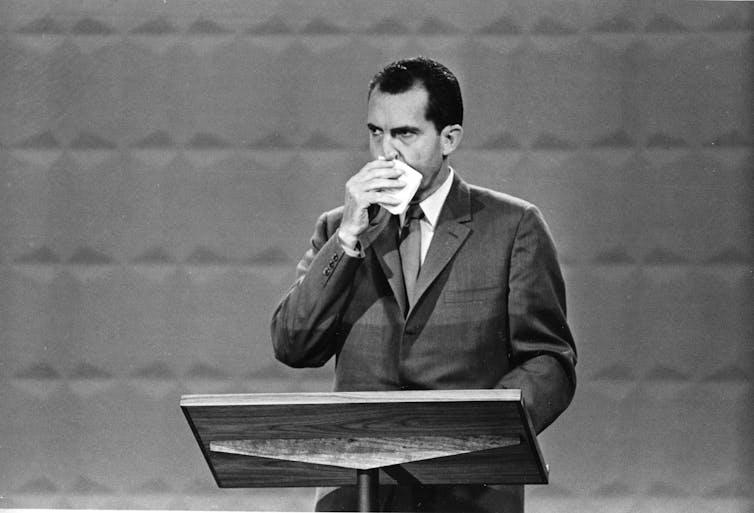

Walter Lippmann, a number one newspaper commentator of the time, mentioned Nixon's behavior at length in his column the day after the controversy, saying the tv cameras “were very hard on Mr. Nixon. … They made him look sick, which he is not, and they made him look older and more worn out than he is.”

This effect, Lippmann wrote, “was a misrepresentation and we need to ensure for the future that the cameras are indeed impartial.”

Related Press

Doubts concerning the impact of television

However, one other columnist, William S. White, questioned the powerful impact of television on politics, writing: “There is, after all, no magic formula for getting to the presidency on electronic waves: no gold mine of easily won votes in television heaven.” Television was nothing recent in 1960. About 87% of American households Back then, everyone owned not less than one television set. But the role of television in American politics was still changing.

Of greater importance, not less than to some analysts, was Nixon's tactics throughout the debate. For example, he seemed inclined to debate things the best way Kennedy had presented them. In his opening statement, Kennedy said: expressed dissatisfaction with the direction of the country Amid the uncertainties of the Cold War, he said, “This is a great country, but I think it could be an even greater country; and this is a powerful country, but I think it could be an even more powerful country.” He concluded his opening remarks by stating, “I think it's time for America to get moving again.”

Nixon, speaking after Kennedy, denied that the country had “stood still” throughout the Eisenhower years, but said, “I fully agree with the spirit that Senator Kennedy expressed tonight, the spirit that the United States should move forward.”

He concluded his opening speech with the words: “I do know that Senator Kennedy feels these issues just as deeply [facing the country] like me, but our disagreement will not be concerning the goals for America, only concerning the means to attain those goals.”

Whether Nixon was attempting to curb his combative tendencies or appeal to wavering Democrats, his remarks seemed strangely defensive and respectful.

“Nixon was so insistent that he shared all of Senator Kennedy's worthy goals that one could expect Nixon to support the Democratic program at any moment,” columnist Joseph Alsop wrote sarcastically just a few days after the controversy.

So what modified the consensus on the primary debate from a tie to Nixon's on-air destroy? The answer undoubtedly lies within the seek for a post-election explanation for Kennedy's victory. He won the referendum by 0.2 percentage points or around 118,000 votes.

Historian of Campaign 1960 have identified that numerous variables could have influenced the end result in such an in depth race. But political journalist Theodore H. White writes in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Making of the President, 1960”, argued that the televised broadcast of the primary debate was crucial.

“Until the cameras were on the Senator and the Vice President,” White wrote in his 1961 book, “Kennedy was the boy the Vice President had attacked and harassed as immature, young and inexperienced. Now he was obviously the Vice President's equal in flesh and blood and in behavior.”

Whether television was so enlightening and conclusive is debatable. Less controversial, nonetheless, is the sensation today that television made a difference. As historian David Greenberg wrote about this primary televised debate, “the perception The influence of television changed American politics and shaped the behavior of politicians and candidates for decades.”

One could easily add to this remark: the perception of the influence of television similarly modified the overall opinion concerning the very first presidential debate.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply