The impressive statue of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, DC shows Abraham Lincoln standing while a person dressed only in a loincloth appears to rise from a kneeling position.

The face on the monument is that of Archer Alexanderwho escaped slavery in 1863 by fleeing to St. Louis, Missouri. Fundraising for a monument was began in 1864 by Charlotte Scott, who had been enslaved in Virginia before moving to Ohio, but she was not the designer of the monument.

As a Art historianI argue that the origin and evolution of this image illustrates how ideas can change over time.

History of design

The memorial in Washington combines the portrait of an actual person with a typical symbol that has electrified abolitionists for nearly 100 years: the generic image of a kneeling slave.

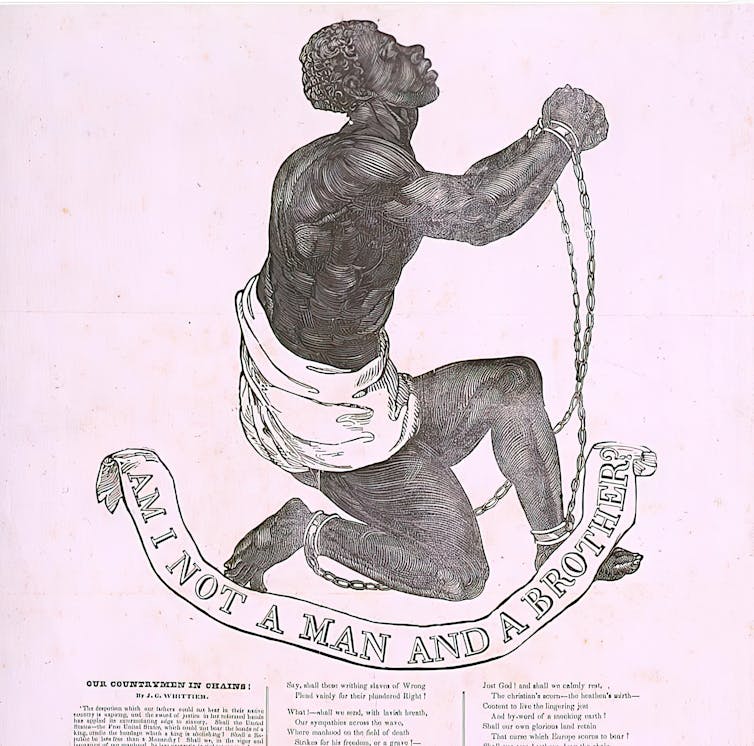

The image of the kneeling man in chains was first utilized in a seal commissioned by the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave TradeFounded in 1787 by English Quakers. The seal shows a kneeling slave folding his sure hands and asking: “Am I not a man and a brother?”

Manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, British modeler William Hackwood/The Metropolitan Museum, New York

The picture was so popular that in the identical yr the extremely successful The English porcelain company Wedgwood Manufactory produced a medallion with the identical image and slogan that was widely circulated.

Two years later, in 1789, firstly of the French Revolution, The Sèvres manufactory created a French version with the interpretation: “Am I not a man? A brother?”

In France, the Count of Angivillier, a minister under Louis XVI, stopped production of the medal. The Princeton University Art Museum label states that he feared the image could encourage enslaved Africans in French colonies to rebel.

The phrase “Am I not a man and a brother?” has been widely related to the history of emancipation. The exact words of the previous slave and abolitionist Sojourner Truth on the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in 1851 are lost to history. However, it was widely reported that she used the refrain “Am I not a woman?” – the parallel to “Am I not a man” – to advocate for ladies's rights, which included black and white residents alike.

In 1837, the American poet John Greenleaf Whittier wrote the pamphlet “Our countrymen in chains”, clearly describing the enslaved person as a citizen and speaking of the horror of a market-oriented America: “What! God’s own image bought and sold! Americans are being driven from the market and exchanged like animals for gold!”

The brochure was illustrated with a woodcut depiction of a person in chains, modeled on the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, in addition to the medallions of Wedgwood and Sèvres.

Library of Congress

Controversial reception

The sculpture was controversial from the start. At the inauguration of the monument on April 14, 1876, Frederick Douglass gave the keynote speech: Failure to check with the imagery of the monumentFive days later, he criticized the design in a letter to the National Republican newspaper in Washington. He hoped for monuments that will show “the Negro not on his knees like a four-legged animal, but upright on his feet like a human being.”

Boston erected a replica of the monument in 1878. However, in June 2020 The city decided to remove the statuebecause its meaning had develop into contested. Unaware of the long history behind the image, contemporary viewers often perceived a racial hierarchy within the depiction. They ignored the historical moment of emancipation and infrequently assumed that any white man standing next to a kneeling black man was a degrading image.

Symbols that were effective in a single time and place don’t all the time translate to recent situations. I consider that our current ideas is not going to be the last either.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply