If you simply knew Bob Newhart as an actor – especially because the star of the legendary “Bob Newhart Show” but in addition in minor memorable role within the movie “Elf” – chances are you’ll not have considered him as a literary character.

But Newhart, the died on July 18, 2024began his rise to stardom on the age of 94 as a humorist, writing and performing sensible monologues comparable to “Driving instructor” And “Bus driver school.” In these plays he demonstrated a mastery of diction, dialect, characters and dialogue that deserves the title of “Master of Literature.”

In my opinion, there’s probably no more suitable recipient for the Mark Twain Prize as Newhartwho received it in 2002.

As a Literary scholarI normally study traditional poetry and fiction by canonical authors like Twain and Edgar Allan Poe. But mastery of language and character shouldn’t be just reserved for poets and novelists. Newhart has shown that stand-up comedy could be an art form too.

“The old humility”

One of his masterpieces is his “Abe Lincoln vs. Madison Avenue“Stand-up routine built on a unusual but timely premise.

Having witnessed the rise of promoting and public relations within the Nineteen Fifties and Nineteen Sixties, Newhart imagined a scenario from an earlier era. What would have happened, he wondered, if there had been no real man with the intellect and stature of Abraham Lincoln in the course of the American Civil War?

The promoting industry, he continues, “should have created a Lincoln.” He then stages a one-sided fictitious phone conversation between a press agent and an individual hired to play the role of this fabricated Lincoln – and introduces it with a sentence that may change into iconic for Newhart: He says the conversation went “something like this.”

The resulting “something” is a precisely crafted, six-minute number worthy of the term “poem.” In fact, Newhart employed a number of the same literary devices utilized by earlier masters comparable to Twain and Alexander Pope.

Like Twain, Newhart had a beautiful ear for dialect and peppered his monologue with little bits of slang and jargon to capture the casual manner of speaking of a stereotypical press agent.

“Hi, Abe, honey, how are you, boy?” he begins. “How's Gettysburg?”

The lines are delivered quickly and casually, like so a lot of Newhart's stand-up routines, subtle but effective – they hit the nail on the pinnacle without being too on-the-nose. He uses similar little linguistic subtleties throughout the piece – like when the agent refers to “Four score and seven,” the famous first words of the Gettysburg Address, as a “grabber.”

Herein lies one other, even stronger, source of humor. Lincoln's opening is famously lyrical and formal, the epitome of oratorical eloquence, and the agent has reduced him to a “grabber.” This type of deflation recalls an old satirical genre often called the “mock epic.” As practiced by the Enlightenment-era English poet, translator, and satirist Alexander Pope and others, it derives its humor from the contrast between the sublime and the mundane and even ridiculous.

Newhart returns to the device when he has the agent explain to fictional Abe the logic behind the road “The world will hardly notice and long remember.”

Lincoln's original line is graceful, alliterative and almost perfect iambic – an oratorical gem if ever there was one – but to the agent, it’s just “the same old humble number.”

Character is crucial

Masters of humor, and even fiction typically, will inform you that character is essential. If you get the characters right, the humor—or drama—will follow.

With his splendidly subtle ideas, Newhart paints a hilarious picture of the naive idiot the agency must transform right into a Lincoln. And as is usually the case with humor, irony helps to realize the specified effect – on this case, humor.

Lincoln was an eloquent, noble personality. He was larger than life – and definitely larger than that idiot who doesn't even get the joke when one in every of the agency's “gag writers” supposedly writes a line about General Ulysses S. Grant.

The agent shares it with the fallacious Abeand said, “They've put Grant under a lot of pressure. Next time they pester you about Grant's drinking… tell them you're going to find out what brand he's drinking and send a case of it to all your other generals.”

After a temporary pause, the agent says, with Newhart's famous stutter, “Uh, no, no, it's, it's like the brand was, uh, the reason he won.” Finally, after one other temporary pause, the agent snaps in exasperation, “…use it, it's funny.”

Give the audience recognition

This final “exchange” demonstrates essentially the most ingenious aspect of Newhart’s humor: his trademark one-sided conversation, which he also used to hilarious effect in “Driving Instructor” and other numbers.

Now why the Opening sequence In “The Bob Newhart Show,” Newhart answers the phone – a tribute to his then-famous stand-up gag.

We never hear “Abe's” voice, only the agent's side of the conversation. This may look like a small detail, but this device signifies that we because the audience need to play an energetic role within the comedy. We hear the agent's side and must imagine what he hears. Sometimes the agent repeats what he claims to listen to, but on this case, when the agent tries to clarify the punch line of the Grant joke, the burden is on us.

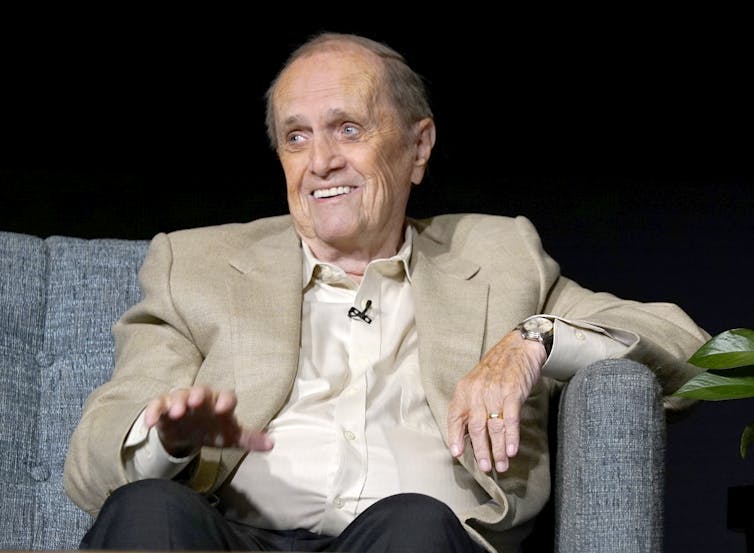

Vince Bucci/Invision for the Television Academy/AP Images

Here, too, Newhart used an old stylistic device. In a dramatic monologue like Robert Browning’s serious poem “My Last Duchess“ the poet leaves out necessary details, forcing us to seek out them out and complete the partially told story.

This device is especially effective in comedy because, as Newhart knew on some level, all of us prefer to feel smart. By putting us able to fill within the gaps within the conversation, Newhart gives us the chance to feel a little bit more satisfaction and generate some humor ourselves by creating our own picture of the redneck on the opposite side of the conversation.

It was a masterstroke by a master of his craft. With this sensible touch, Newhart turned us all into comedians.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply