Great-grandmothers. We all have them. But most of us won’t ever know them except through fleeting glances at fading scraps of paper: sepia photographs, recipe cards, handwritten letters written with a fountain pen full of cocoa-colored ink.

What does it take to construct coherent stories from such exciting fragments of life? This query has been a continuing in my profession as Professor of nineteenth Century Literature and Culture. I recently used this experience to jot down a book about my circle of relatives.

Andrea Kaston Tange

When I inherited my great-grandmother's diary, a repurposed teacher's planner wherein she documented the family's move from Michigan to Miami in 1926, I discovered a marriage portrait inside. The slanted profile shows her youthful skin and a dress too elaborate for the on a regular basis wear of a Midwestern teacher. It's easy to assume that she took enjoyment of writing her recent name on the back of the image: Faith Avery.

I stared at her beautiful picture for years, as if details of her satin dress could explain why a girl widowed in 1918 refused for the remaining of her life to confess she had had that first husband, and yet fastidiously preserved that portrait.

And then, because archives are at the center of my academic work, I started researching. I searched for marriage certificates and military service cards, studied maps, and located relations in censuses and obituaries. In these documents I discovered surprising and poignant answers.

What was I searching for? How can someone who only half tells their family history uncover more truths? And what does it take to know them?

Andrea Kaston Tange

The digging

Questions that begin with “why” are rarely easy to reply, so researchers prefer to start out with “who,” “when,” and “how” by locating an individual in a single place after which tracking them through time. There's a technique to this adventure down the rabbit hole.

Make a listing of unknowns. These may be facts or tantalizing tidbits of incomplete family history. My mother tried to be helpful and told me things like, “Faith always said there was a horse thief in the family, but she was too ashamed to reveal his name” and “I think Aunt Harriette (Faith's sister) was briefly married once.”

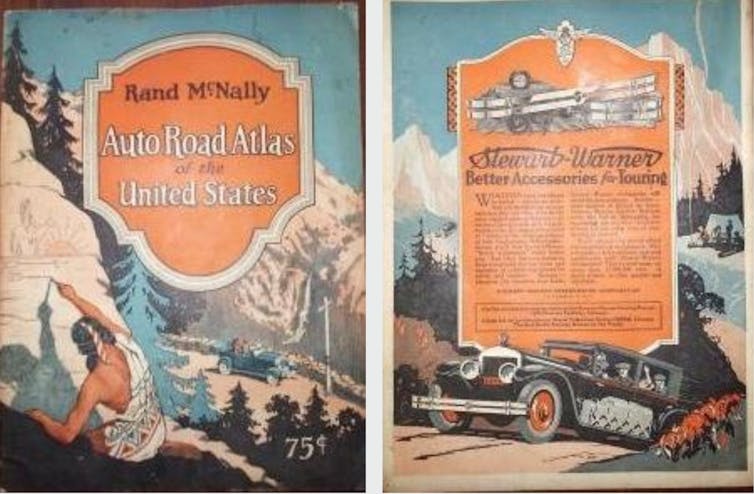

Do precise, not general searches. Typing “horse thief Avery” into Google won’t yield anything useful, but many other sources contain precious details about old-fashioned heroics. The New York Public Library Guide to family research presents some options. The Library of Congress Print and Photograph Collection also can aid you imagine the world of your ancestors. Physical libraries contain historical photos, maps, local records, and digitized newspapers that should not available online. Historical societies and state universities typically allow free personal use of their collections.

Be aware that sometimes you’ll fail and should change course. I looked for the horse thief for several days to no avail, much to my mother's disappointment. But after I turned to Aunt Harriette's marriage, I discovered a personality no less fascinating, one I now know as “Four Wives Frank.”

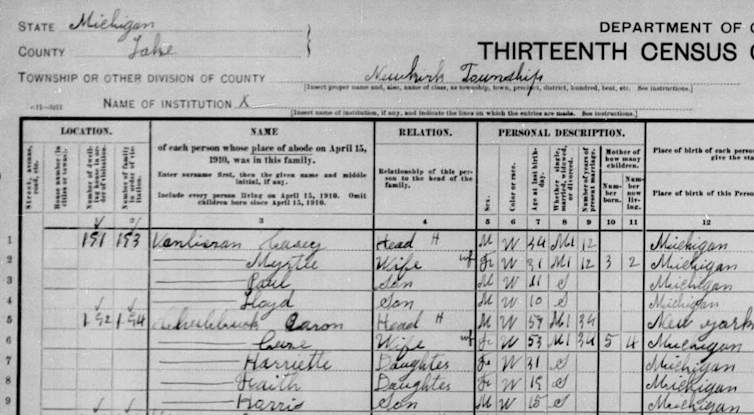

Read old documents when that they were created by a various group of people that took information on a whim. The handwritten birth, death, marriage and Census records of the past centuries were based on self-reported data that didn’t require verification. They can suffer from negligence within the name of efficiency.

One hasty census taker recorded Faith's mother, Cara, as “Cora,” one other renamed her brother, Horace, “Harris.” Frank listed a series of birth years, countries of origin, and maiden names for his mother as he made his way west. He will need to have been charming. Who but a captivating man could have persuaded woman after woman to marry him, each of whom thought she was at most his second wife? The registrars and census takers, not to say his trail of brides, were none the wiser.

The US National Archives and Records Administration

Which leads me to this: Check the data. I knew I had the suitable Frank because several records listed the identical three sons. Inconsistencies in those records, and combined along with his life history, made this conclusion inescapable: The man consciously reinvented himself.

The Assembly

My academic work has taught me that almost all Archived answers result in further questions. So I expect several phases of collecting. I gathered every little thing I could find about Faith's youth, hoping that something might explain her reticence about her first marriage. As her story got here to light, I kept coming across gaps within the narrative that prompted me to dig even further.

Andrea Kaston Tange

It is simpler to know people when you’re aware of their world. For background, I read stories about Miami within the Nineteen Twenties and looked in Faith's diary for details which may reveal her personality or motivations. As I combed through her reading lists, I discovered a girl who enjoyed popular entertainment, resembling the blockbuster “Aloma of the South Seas.“ Primers from Wages and costs within the Nineteen Twenties explained the family's financial worries.

As I got to know Faith higher, I checked out the documents again and asked myself recent questions. To discover if Harriette's husband Frank had anything to do with Faith, I created timelines for each sisters. To think in regards to the emotional background of those events, I reread Faith's diary, paying particular attention to the entries about Harriette and Faith's second husband.

Since each stack of documents accommodates multiple stories, the important thing to a coherent narrative is to seek out a typical thread that addresses the most important puzzles while identifying the lesser ones. I let the horse thief loose.

The results

The detective actions of what I “investigative memoirs” might encourage you to do your personal family research. Genealogy web sites like Ancestry.com And FamilySearch.org can assist.

But it's vital to do not forget that reading more information enriches any family history, and native librarians are exceptionally good at helping users find what they're searching for.

As improbable as it might sound, Four Wives Frank helped me understand how big Faith's secrets were, and that she kept them within the hope that her children's lives can be easier. Such self-sacrifice is common amongst moms. And yet their details are as individual as the marginally silvery portrait of the gentle young woman who married Harold Avery in 1911 and whose story requires a whole book to inform properly.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply