The dietary label, that black and white information box that you simply see on almost every packaged food within the USA since 1994has recently turn out to be an icon for consumer transparency.

Out of Apple’s “privacy nutrition labeling””, which reveal how smartphone apps handle user data, to a “Label “Garment Facts” The company is standardizing ethical claims on clothing, and policy advocates across industries are citing Nutrition Facts as a model for empowering consumers and creating socially responsible markets. They argue that intuitive information corrections could solve a wide selection of market-related social ills.

But the history of this familiar, on a regular basis product name is complicated.

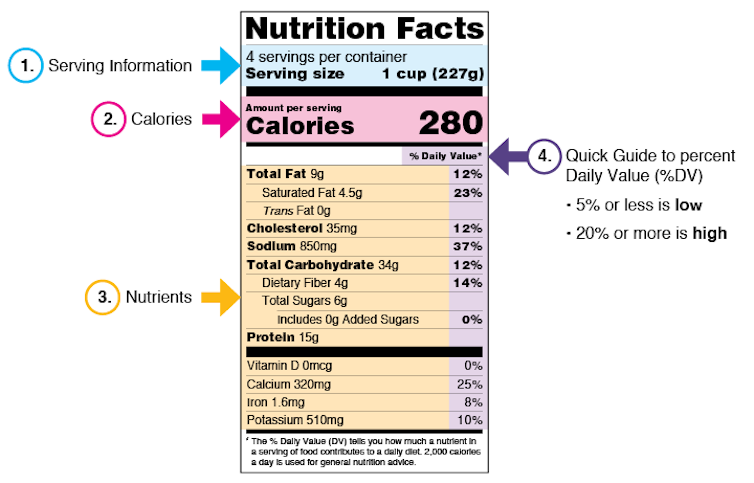

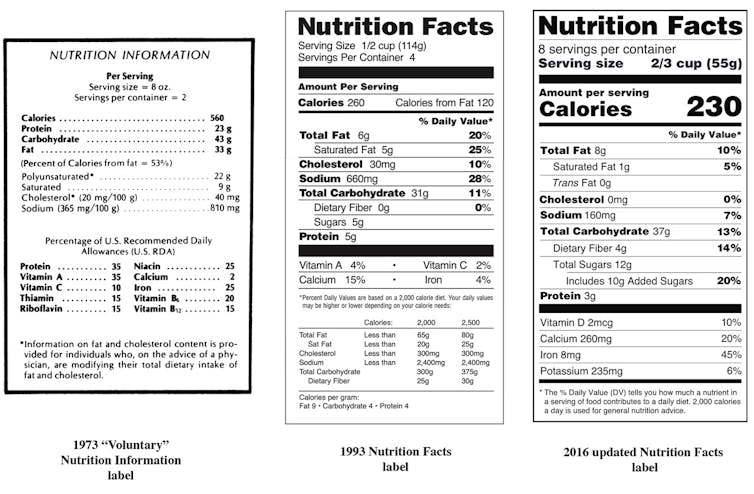

I study Nutritional regulation and food plan culture and have become thinking about the dietary label once I read the story of Food and Drug Administration guidelines on food standards and labeling. In 1990, Congress passed the Law on dietary labelling and datarequire nutrition labels on all packaged foods to deal with growing concerns concerning the increasing variety of chronic diseases related to unhealthy diets. The FDA introduced its “Nutritional Information Panel in 1993 as a public health tool that empowers consumers to make healthier selections.

The most evident purpose of nutrition labeling is to let consumers know the dietary value of a food. In practice, nonetheless, this labeling does greater than just inform shoppers. It also embodies a wide selection of political and technical compromises about how one can package the nutrients in foods to satisfy the various needs of the American people.

Where do the “% Daily Values” come from?

The percent Daily Value (DV) information on the label doesn’t all come from the identical source, reflecting the various health objectives that apply to the label.

Recommended values for micronutrients akin to vitamins are based on Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA)by the National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Recommended each day amounts for vitamins were developed out of historical concerns about malnutrition and meeting minimum requirements.

The Daily Values raise two fundamentally different concerns. The numbers for micronutrients represent a lower limit: the fundamental vitamin needs that a toddler should meet to avoid malnutrition. The numbers for macronutrients, alternatively, represent an upper limit: a goal upper limit that adults mustn’t exceed in the event that they want to forestall future health problems brought on by eating too many high-sodium or high-fat foods.

Food and Drug Administration

Why 2,000 calories?

The FDA 2,350 calories almost consumed as the idea for calculating the each day values, because it was the really helpful population-adjusted average calorie requirement for Americans aged 4 and over. But in keeping with Resistance from health groups Because the FDA feared that the upper start line would result in excessive consumption, it opted for two,000 calories.

FDA officials considered this number to be less prone to be “misinterpreted” as a person goal, since a round number implies less specificity.” This implies that 2,000 calories will not be actually a goal for many American consumers who read the label. Instead, it’s an example of public health’s preoccupation with collective risks – what one scientist calls “treating sick populations, non-sick individuals.”

By selecting a round number that was easy to calculate and a calorie count that was lower than the common American's, FDA officials favored practicality and utility over accuracy and objectivity. They argued that endorsing the lower 2,000-calorie baseline would counteract Americans' tendency to overeat and do more good than harm to the population as a complete.

Who determines the portion sizes?

According to the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, portion sizes should reflect:a commonly used amount.”

In practice this implies Routine negotiations between the FDA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which also sets portion sizes for dietary guidelines, akin to My plate – and food manufacturers. Each of them conducts research into consumer expectations and food consumption, bearing in mind how a food is ready and “typically eaten.”

Portion sizes are also determined by product packaging. For example, a soda can is usually considered a single-serving container and is subsequently just one serving, no matter what number of fluid ounces it comprises.

Really Happy

What's in a reputation?

The label was almost called “Nutritional Facts” or “Nutritional Guide” to emphasise that the each day values were recommendations. Then-Deputy FDA Commissioner Mike Taylor proposed “dietary information“ to sound more legally neutral and scientifically objective.

The recent design – an easy, black Helvetica text on a white background that uses indented subgroups and hairlines for readability – and the authoritative, daring title helped establish Nutrition Facts as an easily recognizable government brand.

This led to imitators in other policy areas: firstly, “Drug Factsfor over-the-counter medicines, then consumer protection initiatives in various technology sectors, such as Federal Communications Commission “Broadband Facts” and “AI Nutrition Facts”.”

The dietary table has remained largely unchanged because the Nineties, despite some updates like adding lines for trans fats in 2002 and for added sugars in 2016 to reflect changing public health priorities.

New ways to calculate the facts

The introduction of the nutrition label required the event of a very recent technical infrastructure for dietary information. The translation of the various American food plan right into a uniform set of standardized nutrients required recent measures, test procedures and standard references.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

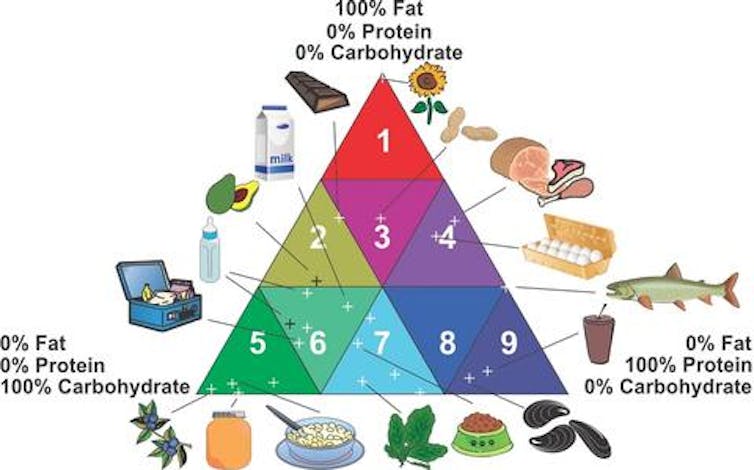

A key player in the event of this technical infrastructure was the Association of Official Analytical ChemistsIn the early Nineties, an AOAC working group developed a Food triangle matrix Classifying foods into categories based on their carbohydrate, fat and protein content. The goal was to find out appropriate methods for measuring dietary properties akin to calories or sugar levels, because the physical properties of the food would affect the performance of any test.

The legacy of the nutrition label

Today, public-private collaborations have further developed this translation of foods into simplified nutrient profiles by making dietary information plug-and-play. USDA FoodData Headquarters provides a comprehensive database of individual ingredient dietary profiles that manufacturers use to calculate dietary information for brand spanking new packaged foods. This database can be used as the idea for a lot of food plan and nutrition apps.

The analytical tools developed for the nutrition label have helped create the fundamental information infrastructure for today’s digital food plan platforms. However, critics argue that these databases present an excessively reductionist view of food as a mere Sum of its nutrientsThis ignores how the various types of a food – akin to its moisture content, fiber content or porous structure – affect the way in which the body metabolizes nutrients.

In fact, many nutrition researchers are concerned concerning the negative health effects of highly processed foods now talk of a Food matrix to emphasise exactly the alternative of what the AOAC was aiming for with its dietary triangle: the necessity for a holistic understanding of the consequences of food on health.

Surprisingly, the largest impact of nutrition labelling could have been that the food industry Reformulate products to attain appealing nutrient profiles – even when consumers don’t read the labels fastidiously. Although intended as an academic tool, in practice I imagine nutrition labels functioned more like a market infrastructure, adapting food supply to changing dietary trends and public health goals long before consumers find those foods within the supermarket.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply