Protests after elections should not unusual in Venezuela. In 2018, people took to the streets to Competition President Nicolás Maduro re-election; She 2019 again when the Venezuelan opposition arrested National Assembly member Juan Guaidó as interim president and thereby disregarded a vote that they believed was rigged.

It is subsequently not surprising that Large-scale demonstrations within the country after Maduro claimed victory again, this time against his challenger Edmundo González within the controversial election on July 28, 2024.

Many within the country had seen the vote as a chance to win six more years of “Chavismo” – a political project that Maduro inherited from former president and left-wing populist Hugo Chávez. Maduro has led the country since 2013, even though it is a severe economic crisisthe results of a mix of falling oil prices, Corruption and mismanagementAnd international sanctionsThe crisis has led to massive inflation And Food shortageswhere nearly all of the population is faced with the selection of living in poverty or leave the country.

But the present protests – sparked by the disputed election results and fuelled by years of economic crisis – are different. Our evaluation of reports reports, social media and the protests themselves shows that they’re affecting a broader section of society than prior to now. Among them are many poor and working-class Venezuelans – the very groups from which Chavismo traditionally draws support.

The big query now is whether or not this more diverse base of protesters can have any impact or whether Maduro will have the option to weather the post-election unrest through repressive tactics, as he has done prior to now.

Controversial result

Given Maduro's claimed victory, protests were all the time likely.

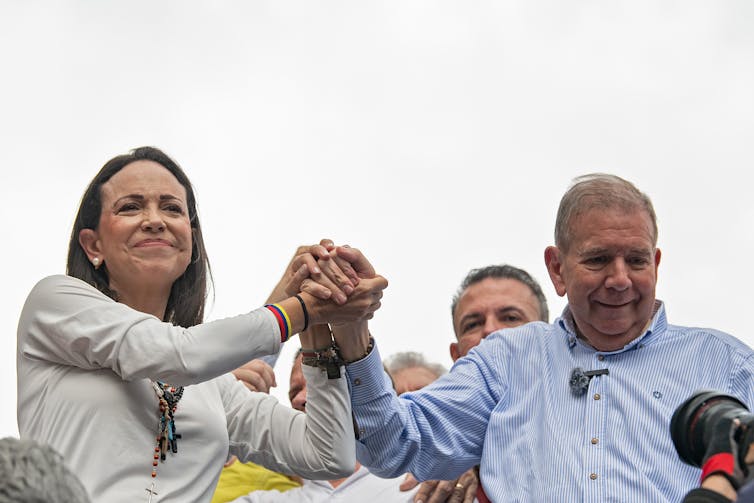

The Fairness of the elections was questioned Months before the actual election because of government interference, akin to the disqualification of Maria Corina Machado – the de facto leader of the opposition – and the arrest of campaign employees and activists.

Alfredo Lasry R/Getty Images

While the opposition was quick to call for a boycott of the elections prior to now, Machado and her alternative candidate González remained true to their election campaign this time.

The Venezuelan Electoral Council released the outcomes shortly after midnight on July 29, indicating that Maduro won with 51.2% of the votewhile González received 44.2%. This is in contrast to post-election polls and documents collected by the opposition in around 40% of polling stations, which show that González wins with 70% the vote.

The opposition immediately questioned the outcomes, claiming they’d not been verified. International observers Raise doubts in regards to the validity of the result.

The Carter Center, which has been conducting international election commentary in Venezuela for years, published an announcement He said the presidential election couldn’t be considered democratic, adding that the vote “did not meet international standards of electoral integrity at any of its stages and violated numerous provisions of its own national laws.”

The statement added that the election took place “in an environment of restricted freedoms for political actors, civil society organizations and the media” and that there was “a clear bias in favor of the incumbent.”

The actions of the Maduro government have further fuelled speculation. According to the opposition, on the night of the election, documents utilized by citizen observers to confirm the outcomes were weren’t handed over in most polling stations. According to The Venezuelan journalist Eugenio MartínezBallot papers were only handed out in half of the country’s 30,026 polling stations.

The government has not yet released results that could possibly be used to verify or refute one side's claim to victory. Politicians from across the region, including Chilean President Gabriel Boric, the Biden administration and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva have since called on Maduro to announce the total results.

Pots and pans protest

Protests against this lack of transparency began the day after the election and proceed. While such mobilization against the federal government has turn into a feature of Chavista Venezuela, the present protests are characterised by the range of individuals taking to the streets.

Venezuela's middle and upper classes have often taken to the streets en masse to oust Maduro from power, sometimes encouraged by radical opposition voices calling for undemocratic means to achieve this. This opposition has been fuelled by quite a lot of aspects, including the federal government's clear turnaround towards authoritarianism and power maneuvers which have undermined democratic institutions.

But this wave of protests was also characterised by mass participation by low-income and working-class people. While the protests by Venezuelans breaking out Although the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on poorer neighborhoods in 2019 isn’t yet fully understood, it was smaller and fewer lasting than in recent days.

Videos of residents in poorer areas akin to Petare, CatiaValles del Tuy and other historical fortresses of Chavismo were shared on social media, with residents banging pots, burning tires and marching within the streets.

“Cacerolazos” – a conventional protest practice wherein pots and pans are banged together – could even be heard in the previous Chavista stronghold where the Mountain Barrackswhere the mausoleum of Chávez, who died in office in 2013, is situated.

Elsewhere, statues of Chávez and posters of Maduro were torn down and smashed in response to outrage over what was seen as blatant manipulation that went too far.

“You have gone too far” is a chorus This has been heard among the many demonstrators because the election.

While media have pointed to protests within the barrios – the term for urban, low-income neighborhoods in Venezuela – starting from spontaneous to somewhat more organized, the federal government has described the demonstrations as coordinated events of “fascist rights“ and funded by the United States.

Offer another

Maduro's refusal to acknowledge that his former supporters are actually protesting against him reveals the large gap that has opened up between Venezuela's Chavista government and its traditional base.

Of course, protests in poorer neighborhoods mustn’t be confused with committed support for the opposition. For years we now have observed that the people within the barrios of Venezuela distrust and are disillusioned with each the federal government and the opposition.

Photo by Raul Arboleda/AFP via Getty Images

But these protests suggest that disgust with the present political system and outrage over alleged electoral fraud are the true reason for this discontent.

The protests are a response to years of crisis, corruption, fiscal irresponsibility and shortages which have torn families apart. 7.7 million Venezuelans have left the country the country to flee these problems. The problems affect everyone in Venezuela, but are particularly devastating for low-income people.

At the identical time, Machado's growing popularity has made many Venezuelans more hopeful. After spending much time campaigning in rural and working-class communities, she and González appeared to offer an alternative choice to the present situation.

Maduro's response

The query now is whether or not this modification within the demographics of the protesters will make a difference.

The Maduro government has signaled that it will remain inflexible in view of the massive demonstrations, Take all essential measures to stay in power. Although that is unlikely, protests in poorer neighborhoods could persuade certain factions inside the federal government that Chavismo has lost the support of the people it claims to represent.

Pressure from inside the federal government itself, in addition to objections from regional leaders, could potentially influence Maduro's political calculations.

But past experience suggests a distinct response. After the waves of protests in 2017 and 2019, Maduro resorted to extreme repression by state security forces and non-state armed groups – often called “Collectives” – whose members are loyal to the federal government and have much to lose within the event of regime change. Government has unleashed massive lethal violence in poorer neighborhoods when it feels threatened. Much of this repression, consisting of police and military raids, was portrayed as crime fighting. But as our research has shown, it also goals to contain social unrest.

Maduro's response will likely include violence against traditional opposition groups which have long mobilized against the federal government, but we consider poorer Venezuelans, who’re turning out to protest in unprecedented numbers, will suffer essentially the most.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply