Following the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump, the Vatican released an announcement on July 14, 2024, condemning the violence. The attack, it said, “hurts people and democracywhich causes suffering and death.”

Other Catholic leaders also expressed concern concerning the political violence.

Archbishop Timothy Broglio, for instance, president of the US Bishops’ Conference, said in an announcement “Together with my brother bishops, we condemn political violence and pray for President Trump and the dead and injured. He also called for an end to “political violence,” which, he noted, is “never an answer to political differences.”

This assassination comes at a time of violence and war around the globe. The conflict in Ukraine has been occurring for greater than two years after the invasion of Russia and the war within the Gaza Strip, triggered by a Hamas Terrorist attack on Israeli civilianshas been occurring for months.

As a Specialist in medieval ChristianityI do know that Catholic views on the morality of killing have evolved over time. And while Christianity eventually got here to just accept the Idea of warfare for self-defense and the common goodThe value of forgiving enemies was also emphasized.

Early Christianity

In the primary centuries of Christianity, when it was banned within the Roman Empire, it was considered the faith of those that were considered weak, comparable to women and slaves. Christians were generally pacifiststo cover during pursuit or to undergo arrest without physical force.

In fact, bloodshed was so abhorrent to some Christians that not less than one local church congregationpresumably in Rome or North Africa, soldiers couldn’t be received into the Christian community as “catechumens” – those preparing for baptism – unless they refused to offer an order to kill others. Any catechumen or baptized believer who desired to turn into a soldier needed to rejected by this community due to “contempt” God.

However, some Christians served within the Roman army, but by the tip of the third century they were excluded from the military within the eastern a part of the empire in the event that they refused to supply sacrifices to the pagan gods.

Morality of killing

Christianity was legalized originally of the fourth century and progressively developed into the official religion of the Roman Empire until its end. Christian theology has had to vary over the centuries regarding the morality of killing, including murder, capital punishment, and warfare.

An vital change was the notion of self-defense. The theologian Augustine, who died in 430 AD, taught that a Christian nation has the proper to wage war under certain conditions: There should be a War in self-defense; the last word goal should be peace; it should be conducted without cruelty; and it must not be an offensive war of conquest. To achieve peace, it was acceptable to kill other soldiers or fighters, including the leader of the enemy army.

In 732 AD, for instance, a Christian army led by the Frankish nobleman Charles Martel conquered defeated a Muslim army which had already conquered most of Christian Spain. His victory on the Battle of Tours stopped the spread of Muslim rule into Gaul and further into Christian Europe.

But neither the church nor the state at all times adhered to those principles. The founding of the Inquisition within the early thirteenth century – initially to Ensuring fair investigations accused heretic – was later suffering from abuses comparable to restrictive detentions and brutal torture, which led to the deaths of tens of 1000’s.

Acting for the common good

Later medieval theologians expanded the thought of self-defense and added one other condition: the defense of the common good.

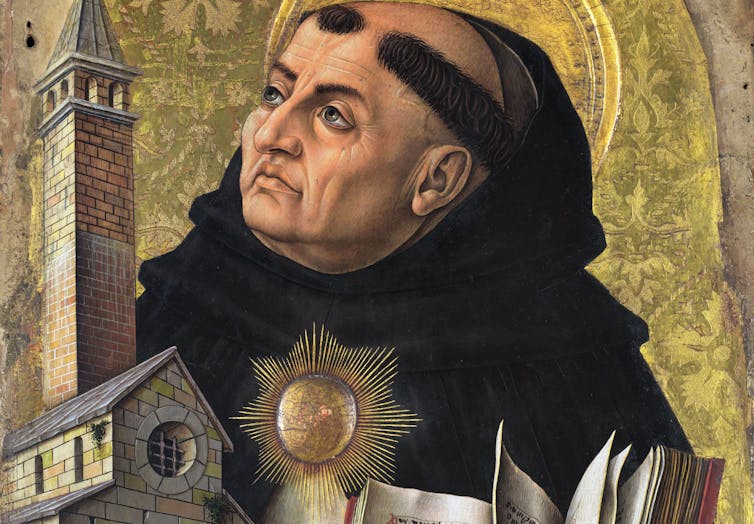

One of an important thinkers on this topic was the thirteenth century Dominican Father Thomas Aquinas. In his extensive work “Theological Summary“, Thomas Aquinas offers an in depth consideration of the conditions under which war can legitimately be waged.

Carlo Crivelli via Wikimedia Commons

But in one other work – “On the Government of the Rulers”, co-authored with Bartholomew of Lucca – Thomas Aquinas discusses a related query: What happens when a community is oppressed by an extreme tyrant who puts his own desires above the welfare of the community he rules and doesn’t let up?

In this case, a bunch of community leaders acting in the most effective interest of the common good can depose or kill the tyrant. However, a single person, a lone killer, cannot take matters into his own hands and act on his own.

Later perhaps the leaders of the American Revolution unconsciously reflected This principle was based on the choice to fight for independence and to withstand the tyranny of the British Parliament and King, which they perceived as unjust.

Both basic values, self-defense and customary good, are still being taught

Today within the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Human life is sacred, and no individual has the proper to take a lifeBut each individuals and societies have the proper to “legitimate” self-defense.

The Catechism makes clear that the intention should be self-defense, even when it leads to the death of the opposite. Soldiers can have to kill, but they accomplish that with the intention of defending their country, not with a private desire to take a life. Individuals, too, can defend themselves when attacked, with the intention of frightening or incapacitating an attacker, but not with the precise intention of killing him.

The meaning of forgiveness

A 3rd practice doesn’t concern teaching, but prayer: the Forgiveness towards enemies.

This Christian belief has its roots within the Gospels, particularly in how Jesus taught his disciples to hope, referred to as Our FatherChristians are should love and to forgive their enemies, a vital lesson that applies even to those that might attempt to kill them.

It was customary for prisoners sentenced to death to personally forgive the executioner before death. In 1535, for instance, Saint Thomas MoreThe English Lord Chancellor, convicted of high treason, even kissed his executioner before forgiving him.

Even murder victims have often forgiven their attackers. 1902 when she died from her woundsSaint Maria Goretti forgave the person who tried to rape her and stabbed her when she resisted. And in 1996, Christian de Chergé, the abbot of a bunch of Catholic monks kidnapped and later executed by Algerian terrorists, left a final statement during which he addressed his executioner with the words:my friend of the last moment“ and expressed the hope that they’d see one another again in paradise.

Contemporary Popes

The words and actions of recent popes also clearly express the Catholic hope for love and forgiveness within the face of violence.

Following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, Pope Paul VI issued an announcement that very same day during which he not only expressed his own sympathy for the Kennedy family and the people of the United States, but in addition concluded with the prayer “that not hatred, but Christian love, should reign over all humanity.”

When Turkish citizen Mehmet Ali Ağca attempted to assassinate Pope John Paul II in 1981, the Pope, who survived, later visited the person in prison to forgive him personallyAğca was sentenced to life imprisonment in an Italian prison, but was released on the request of the Pope and sent back to Turkey.

Obviously, Catholic teaching on killing has evolved over time and continues to emphasise the worth of human life and the common good. What has not modified is the necessity for forgiveness.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply