Deadly attractions are an ordinary movie plotbut in addition they occur in nature and have much more serious consequences. Conservation biologistI even have experienced them in among the most foreign places on earth, from the Gobi Desert to the Himalayan highlands.

In these places Shepherd communities Camels, yaks and other livestock graze over vast areas. The problem is that the wild relatives of those animals often live nearby and big, testosterone-driven wild males attempt to mate with domesticated or tamed relatives.

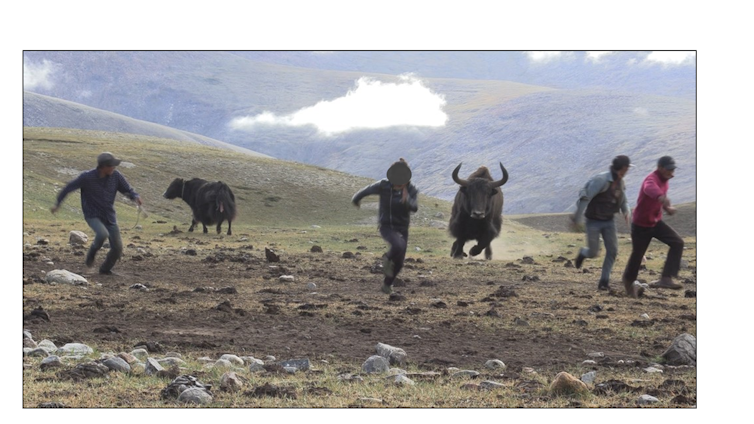

Both animals and humans lose out in these encounters. Shepherds who try to guard their native populations risk Injuries, emotional trauma, economic losses and sometimes deathWild intruders could be chased away, harassed or killed.

These clashes threaten iconic and endangered species, including Tibetan wild yaks, wild two-humped camels And Asia's forest elephantsIf wild species are protected, herders could also be prohibited from hunting or harming them, even when it could be needed for self-defense.

Human-wildlife conflict is a well known challenge world wide, yet clashes in these distant outposts receive less attention than those in developed areas, corresponding to Pumas are moving into US suburbsIn my view, protecting threatened and endangered species just isn’t possible without also helping the herders whose lives are affected by conservation policies.

The urge to mate

The force that drives these attacks is pure biology. All pets are descended from wild ancestors. Over the course of evolution, natural selection has favored males that fertilize essentially the most females – and females that leave behind reproductive offspring of their very own. The attraction can go each ways: sometimes smaller or less aggressive domesticated males mate with wild females.

Many pastoral societies face this challenge. Hindu Kush mountain system In Central Asia and further east, Tibetans, Uighurs, Changpa and Nepalese raise yaks for meat, milk, transportation and shaggy fur for clothing.

Wild yaks were once considered extinct in Nepal until a team led by wildlife biologist Naresh Kusi rediscovered it in 2014Today, aggressive conflicts between domesticated and wild yaks are a significant concern for local herders.

In Africa there are mountain zebras within the Namib Desert, endangered specieshave been bred by donkeysIn northern China and Mongolia, native and reintroduced Przewalski horses coexist in tense zones where herders try to stop genetic exchange. In Southeast Asia, wild cattle species live, like Gaur and bullhave extensively mixed with domestic cattle and buffalo.

In northern realms, caribou and reindeer, which belong to the identical species, Rangifer taranaduseach occur in wild forms. Reindeer have also been domesticated and are central to indigenous pastoral cultures in Scandinavia, Russia, Canada and Alaska. Caribou slaughter and separation efforts couldn’t prevent the interbreeding.

In the temperate zones of Europe and Asia, native species corresponding to Ibexes or wild goatsAnd Argali, the most important wild sheep on the earthcause problems by mixing with domesticated goats and sheep. In South America Guanacos – relatives of untamed camels – occur from sea level to the snow line within the Andes and try and interbreed with domesticated llamas.

Leonard A. Floyd/Flickr

The wild and the tame

All over the world, people breed about 5 billion head of livestockIn most areas, the wild ancestors have long since died out, so herders wouldn’t have to fret about cross-breeding.

The wild relatives that survive are often rare or endangered. For example, there are about 43 million domesticated donkeysalso called donkeys, worldwide. But within the Horn of Africa, the one remaining place with indigenous ancestors, lower than 600 wild donkeys survive today.

The same asymmetry exists within the Himalayan highlands, where the variety of wild yaks – a species extremely necessary to the Tibetan population – is estimated at about 15,000 to twenty,000, in comparison with 14 million domesticated yaksWorldwide, for each wild Bactrian camel, about 2,500 domesticated brothers.

Even in protected areas in northern India, western Mongolia and western China, the population of livestock exceeds that of ungulates. by an element of about 19 to 1.

As wild populations shrink, the remaining males have less mating potential, making them more more likely to hunt domesticated females. But cross-breeding with domesticated animals may lead to the extinction of some wild animals as genetically different species.

No easy solution

It is difficult enough for herders to make a living on the perimeters of the earth without wild animals raiding their herds. Often, sticks and stones are the one legal weapons that herders can use to defend their animals or themselves. Firearms are rare and infrequently illegal, either since the wild species is protected or since the land prohibits or restricts the possession of weapons.

Country beats, CC BY-ND

Global conservation policy recognizes the plight of herders. International Union for Conservation of Naturea network of governments and non-governmental organizations committed to preserving life on Earth, reaffirms that indigenous peoples play a key role in protecting endangered species and preserving the genetic purity of those wild animals.

Many national governments also support the protection of untamed species and the support of nomadic pastoralists, at the least in principle. However, these broad objectives will not be at all times met on the local level, particularly when the people concerned are pastoralists living in distant areas where government assistance is difficult to acquire.

Aili Kang/Wildlife Conservation Society, CC BY-ND

Coexistence in a crowded world

When herders have to protect their herds from other threats corresponding to snow leopards, brown bears or wolves, their principal options are to erect fences, avoid areas where carnivores are present or kill the predators. Shepherds also castrate their pets to stop them from Fights with other animals within the herd or attacks on humans.

None of those options are suitable for coping with wild ancestors of species corresponding to yaks and camels. Castrating wild males or restricting their range makes it difficult to guard and reproduce threatened species.

Fences are harmful because they will prevent wild grazers from moving seasonally to other habitats. Wildlife migrations are necessary not just for the herd: because the animals roam and graze over wide areas, they fertilize the grasslands. Arming ranchers against wayward and aggressive wild males could appear justified, however the destruction of endangered species is a nasty nature conservation path.

Respect for the normal cultural practices of indigenous peoples is very important. international agreements to guard biodiversityIn my view, these human-wildlife conflicts require serious discussions involving ranchers, conservationists, and native and national governments to develop pragmatic strategies.

Without creative solutions to stop interbreeding, more iconic animals will follow the disappointing paths of wild reindeer, bison and other wild species are fighting for his or her survival as they increasingly clash with human society.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply