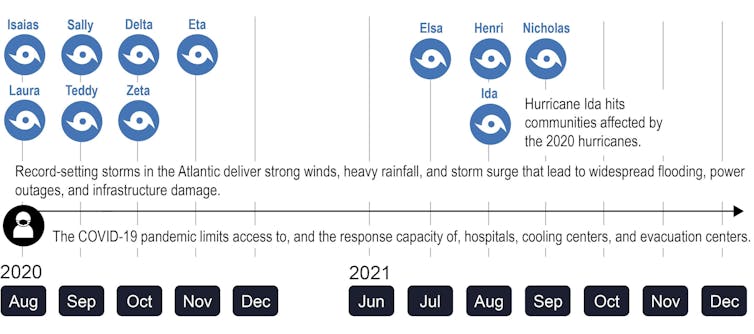

Most Americans will remember 2020 because the 12 months the pandemic modified every little thing. But for Lake Charles, Louisiana, and its neighbors along the Gulf Coast, it was also the 12 months of Record disasterswhen “unique” storms occurred in such rapid succession that their effects overlapped.

A recent National Academies consensus study, on which I participated, examined the increasing disasters facing the region – each physically and socioeconomically – because the pandemic brought storm after storm with little time for recovery.

The study concludes that Lake Charles' experience could also be a harbinger of what lies ahead in a warming world unless the country fundamentally rethinks its disaster preparedness, response and recovery strategies.

Disasters in Lake Charles are increasing

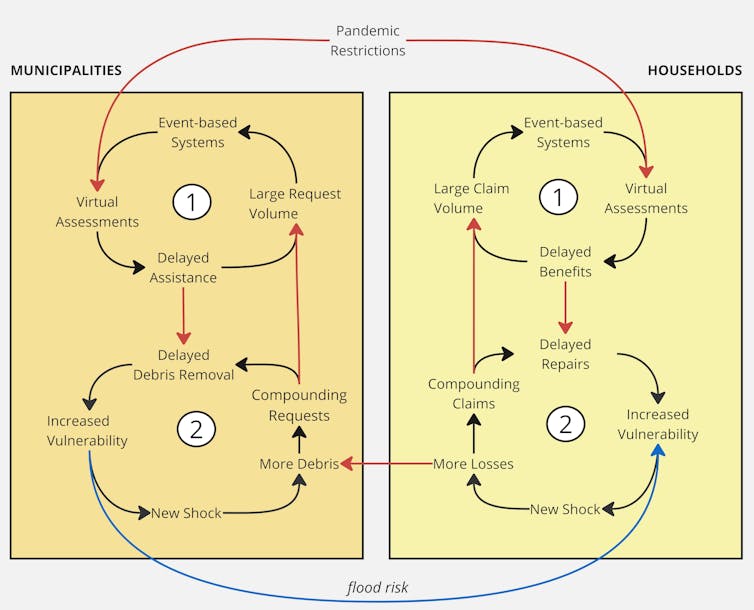

Hurricane Laura made landfall near Lake Charles on August 27, 2020. strong Category 4 stormwith wind speeds exceeding those local constructing codes were designed to guard against. The ongoing pandemic made it difficult to submit assistance applications and insurance claims to FEMA. Assessors could only view properties remotely, and on-site application assistance was suspended, forcing residents to depend on untested online systems.

While the community was still struggling to document its losses itself, Lake Charles was hit again five weeks later by Hurricane DeltaThe storm lashed already damaged buildings and sent debris flying, causing further damage and creating complex damage scenarios.

It was almost unattainable to differentiate latest damage from existing damage that had been made worse by the last storm. Delayed recovery assistance The municipalities lacked the resources to finance further debris removal.

Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty Images

Then February 2021 brought a deep freeze to homes that had not yet been repaired, causing pipes to burst and much more water damage from inside. Tarps protecting the damaged roofs frayed, allowing much more water to seep in from above. More and more debris piled up along the streets.

When Record rainfall In May 2021, stormwater systems clogged with debris were overwhelmed. Floodwaters inundated properties, triggering one other wave of harm in an already overstretched claims and relief system. Uninsured losses increased as flooding reached areas that weren’t expected to flood under “normal” circumstances and subsequently didn’t have to carry flood insurance.

This is what a deepening disaster looks like. The mounting economic damage left many homes unrepaired. Damaged rental properties were quickly taken over by buyout programs or suddenly sold. lucrative housing markets. Lake Charles housing market recovery lags behind til today.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

The events in Lake Charles in 2020 and 2021 highlight a very important truth: The only solution to avoid worsening disasters is to shorten the recovery time after each storm.

This is a difficult prospect with Storms occur more continuously because of climate change. As lead engineer of the study team, I consider it should be needed to prioritize housing resilience, create more flexible support systems, and construct adaptive capability that may handle novel storm scenarios.

1. Build resilient homes

The best solution to shorten recovery time is to avoid the necessity for recovery altogether. That starts with constructing homes that may withstand extreme storms.

Unlike other critical infrastructures, that are strictly regulated, housing construction is subject to the private decisions of the owners, who little or no information concerning the vulnerability of their homes. It is subsequently not surprising that they not realize how break-ins through windows or garage doors could spread and destroy your property.

Worse, the old buildings usually are not required to fulfill the newest constructing codes, leaving the country's aging housing stock particularly vulnerable to worsening disasters.

States could introduce and implement improved constructing standards, but There is a scarcity of political will in lots of Gulf Coast states. In addition to developers’ concerns about rising construction costs, the reform of constructing codes politicized.

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

Adapted from the US Global Change Research Program, Fifth National Climate Assessment, 2023, CC BY-SA

One example is Alabama, where there isn’t any statewide constructing code. Mobile and Baldwin counties have chosen to implement constructing codes. Supplement to the Coastal Construction Actwhich was created after Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Katrina (2005) to strengthen houses beyond the same old minimum requirements. This, along with the Strengthening homes in Alabama grant program led to more homes being built along the Alabama coast with higher standards. Many of those homes were unscathed, as Hurricane Sally Hit in 2020.

These local programs provide a template that will be replicated in states like Louisianawhich also places value on reasonably priced and resilient housing as a part of its Build Back Better strategy.

2. Recognize that one size not suits all

The housing recovery in Lake Charles has been particularly hampered by the rigidity of the country's current disaster relief apparatus, which views each disaster as a single event handled through a standardized and sometimes restrictive process. This has led to significant delays and denial of assistance through the escalating disasters of 2020 and 2021.

In contrast, pandemic relief funds got here to those communities over the identical period and without major restrictions, giving communities the flexibleness to fulfill acute needs and even construct long-term resilience. Communities used the funds to supply emergency rental and utility assistance, reinforce vulnerable infrastructure, and improve flood management capability.

Adapted from National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. Worsening disasters in Gulf Coast communities 2020-2021, CC BY-ND

The Storm Series 2020-21 a dozen Louisianas bankrupted Insurer and left the National disaster fund exhaustedThe Federal Government now has the chance Redesign of national assistance systems to maneuver from a historically rigid, event-based view of disasters to a more flexible perspective that higher takes under consideration the varied and protracted impacts of escalating disasters, in keeping with the needs and capacities of individual communities.

Disasters have gotten more severe today in unimaginable ways when the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act was written 35 years ago. It established how the federal government, and FEMA particularly, helps states and localities prepare for and recuperate from disasters. A revision of the law could mark a very important latest starting for national disaster relief policy.

3. Learning from the pandemic

The pandemic has not only accelerated recovery through flexible financing, but has also forced communities to develop latest capacities for crisis adaptation, which should help them reply to the intensifying disasters that may follow.

The COVID-19 crisis has led to improved data collection and reporting capabilities. We have found that it has also improved coordination inside and between organizations.

And it forced the virtual delivery of services—schools developed online learning systems and doctors popularized telemedicine. These latest technologies were already in use in Lake Charles when storm damage forced schools to shut a day after the primary in-person classes for the reason that pandemic. It's unlikely that such a rapid adjustment would have happened without the months of pandemic constructing that adaptability.

Network for the investigation of structural extreme events (StEER)

Climate change will bring latest weather patterns that transcend the present policies of disaster management agencies, that are crammed with protocols refined from past experience. The ability to adapt can be critical when those policies cannot address disasters few have imagined.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply