Over the course of its long history, the American labor movement has developed a remarkably diverse vocabulary to denounce those deemed traitors to its cause.

Some insults like “Blackleg”, are largely forgotten today. Others, resembling “informant”, today sound more like old-fashioned banter from film noir. Some terms still offer interesting insights into the past: “Fink”, for instance, was used to disparage staff who informed management; it seems to have was derived from “Pinkerton”, the private detective agency that was notorious for strikebreaking during mass actions, resembling the nice railway strike of 1877.

But no word has harmed American staff more consistently and viciously than “scab.”

Any industrial motion today inevitably results in someone being called a strikebreaker, an insult used to denigrate individuals who break picket lines, break up strikes or refuse to affix a union. No one is immune from this accusation: Shawn Fain, President of the United Auto Workers called former President Donald Trump a “strikebreaker” in August 2024, after Trump suggested to Elon Musk that striking staff at one in all his firms ought to be illegally fired.

While working on my book In my book, Traitors: The Story of an American Insult, I learned that strikebreakers were among the many first Americans to be labeled traitors for betraying their very own people.

Strengthening class solidarity

The use of strikebreaker as an insult is definitely comes from medieval EuropeAt that point, crusted or diseased skin was generally considered an indication of a corrupt or immoral character, so English writers began using “scab” as slang for a villain.

In the nineteenth century, American staff began using the word to attack fellow staff who refused to affix a union or to work while others were on strike. By the Eighteen Eighties, the slur was frequently utilized in magazines, union pamphlets, and books to rebuke staff or union leaders who colluded with their employers. The names of strikebreakers were often printed in local newspapers.

Strikebreakers probably became so popular because they aroused an instinctive disgust for anyone who put self-interest above class solidarity.

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

Many union strikebreakers clearly deserve this title. During a strike by Boston railroad staff in 1887For example, the union bombarded its leader with cries of “traitor,” “strikebreaker,” and “sellout” for prematurely giving in to the corporate’s demands at a time when the union’s coffers were mysteriously depleted.

The strongest expression of this shame comes from the pen of Jack London. Today he’s best known for adventure stories resembling “White Fang”, London was also a socialist. Be popular letter from 1915 “Ode to a Strikebreaker” expresses the poisonous contempt that many feel toward those that betray their colleagues:

“After God had disposed of the rattlesnake, the toad, and the vampire, he was left with a horrible substance with which he formed a crust… a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul… Where others have hearts, he bears a tumor of rotten principles… No man has the right to form a crust while there is a pool of water deep enough to drown his body in.”

In 1904, nevertheless, London had written an extended and fewer famous essay, “The Scab.” Instead of denouncing strikebreakers, This essay explains the conditions that drive some staff to betray their very own people.

“The capitalist and labor groups,” London writes, “are engaged in a desperate struggle,” with capital searching for to secure profits and staff searching for to secure a basic lifestyle. A strikebreaker, he explains, “takes from [his peers’] food and shelter” by working once they don't. “He's not a strikebreaker because he wants to be a strikebreaker,” London stresses, but because he “can't get work on the same terms.”

Rather than treating strikebreakers as vampiric traitors, London urges his readers to contemplate strikebreaking as an ethical transgression motivated by competitiveness. It is tempting to assume society as “divided into the two classes of strikebreakers and non-strikebreakers,” London concludes, but within the “social jungle” of capitalism, everyone preys on everyone else.”

Driven to grow to be a strikebreaker

London's words speak to a tough truth. We can illustrate his point by considering the troubling status of black strikebreakers in American labor history.

During their heyday from the Eighteen Eighties to the Thirties, major labor organizations resembling the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor included some black staff and sometimes preached inclusion. The same groupsHowever, it also tolerated openly racist behavior by local associations.

PhotoQuest/Getty Images

Historian Philip S. Foner tells the story of Robert Rhodesa union bricklayer in Indiana whose “white union brothers refused to work with him.” The Bricklayers and Masons International Union of America For such discriminatory practices, Rhodes was fined $100, but his efforts to get money failed and his racist colleagues punished him for trying. Eventually, he was accused of strikebreaking by the union and – in a brutal twist of irony – fined. Rhodes quit and altered careers.

Civil rights activist WEB Du Bois once noticed that in the key blue-collar jobs in America, only dockworkers and miners welcomed black staff. In most areas, they’d to try to affix unions that were often implicitly – if not explicitly – segregated.

To find work as bricklayers, carpenters, coopers, or in other union-dominated trades where racial discrimination was common, black staff often needed to work under conditions that others wouldn’t have tolerated: they offered their services outside the union or took over work that the union had already done while its members were on strike.

In short, they’d to coach strikebreakers.

Class and race collide

It shouldn’t be difficult to see the competing moral claims here. Black staff who had suffered racial discrimination demanded equal rights to work, even when it meant disrupting a strike. Unions saw this as a breach of working-class solidarity, even in the event that they ignored discrimination inside their ranks.

Managers and firms exploited these racial tensions to weaken the labor movement. With tensions running high, brawls between black strikebreakers and white strikers were common. A report on the Chicago miners' strike in 1904 states: “Someone in the crowd shouted 'strikebreakers,' and immediately a rush was made upon the Negroes,” who defended himself The mob was attacked with knives and guns before the town police intervened.

As this ugly pattern repeated itself, a stigma began to cling to black staff. White staff and their representatives, including American Federation of Labor founder Samuel Gompers, often referred to blacks as “Strikebreaker race.”

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

In reality, black staff were only a small percentage of strikebreakers. Strikebreakers were mostly white immigrants who, like their black counterparts, could face discrimination from unions. Black Americans also had a protracted history of labor activism, fighting for union membership, improved working conditions, and higher wages in cities like New Orleans and Birmingham.

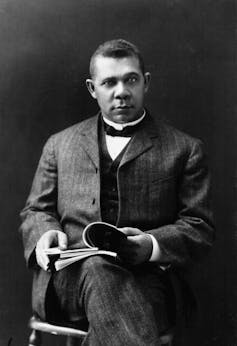

In his 1913 essay “The Negro and the Labor Unions,” educator Booker T. Washington wrote: called on the unions to finish their discriminatory practices that forced black Americans to grow to be “a race of strikebreakers.” Yet this racial stigma remained. Horrific racist violence within the “Red Summer” of 1919 followed hot on the heels of the nice steel strikeduring which non-union black staff were brought in to maintain steel production going.

Prevent divisions amongst employees

While terms like “strikebreaker” and “treason” have often been used to affirm the unity of the working class, the identical terms have also exacerbated divisions inside the movement.

So it will be too simplistic to easily label strikebreakers as traitors. It is essential to know why people must endure contempt, rejection and even violence from their fellow human beings – and to take steps to eliminate this motive.

In 2024, the Canadian Parliament passed a groundbreaking law against strikebreakerswhich prohibits 20,000 employers from hiring substitute staff during a strike.

Not only will this law force firms to answer the needs of their staff in times of crisis, it’s going to also result in fewer divisions inside the union movement – and supply staff with fewer opportunities to grow to be strikebreakers.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply