“Sustainability” and “resilience” have change into buzzwords lately, but many individuals have no idea what these terms really mean. economist who studies environmental issuesI’m convinced that a vital first step in solving an issue is to obviously define the terms.

Although laypeople often use them interchangeably, sustainability and resilience are usually not the identical thing. In fact, resilience shouldn’t be even a single concept. Two influential ecologists have defined “resilience” in two very other ways.

This may seem to be a tutorial debate about words – and in truth not all environmental politicians even know that this conflict exists. But they need to know. Because how we define problems and find solutions is significant.

A transient history of sustainability and resilience

While the word “sustainable” goes back to not less than within the seventeenth centuryThe concept received a serious boost in 1987. At that point, the The World Commission on Environment and Development defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” in its widely acclaimed report “Our common future”.

This was an enormous deal. In the post-World War II era, environmental concerns were expressed prominently and vigorously, for instance by conservationists. Rachel Carson in her book “Silent Source”, but until the UN report of 1987 no appropriate world body had officially recognized the relevance of those concerns. Since then, sustainable development and sustainability have change into popular concepts in academic and political circles.

So that's sustainability. And what about resilience?

1973 Ecologist CS “Buzz” Holling defined resilience in a influential articleHe claimed that the resilience of an ecosystem – ecological resilience – might be regarded as “the amount of disturbance that can be absorbed before the system changes its structure by changing the variables and processes that control behavior.”

In other words, it’s about how much stress a system can withstand before it changes its state. For simplicity, I call this the “Holling definition” of resilience.

To make matters much more complicated, a 1984 article in Natureecologist Stuart Pimm got here up with a second definition of ecosystem resilience, the so-called Develop resilience. According to Pimm, Resilience refers to “how quickly a variable that has gone out of equilibrium returns to it.” “Equilibrium” means a state of balance.

In other words, in response to this definition, a resilient system returns to its equilibrium state after a disturbance. Let's call this the “Pimm concept” of resilience.

How the 2 forms of resilience differ and why this is significant

My research on resilience has led me to 2 vital conclusions. First, Holling and Pimm's concepts of resilience are very different. And second, from a policy perspective, the approach you select should rely upon the state – or states – of the system whose behavior you should influence.

In other words, when you think that a system has just one equilibrium state, then Pimm or technical resilience is the right concept This is because regardless of how strong a shock the system experiences, it all the time returns to its unique equilibrium state once the shock is removed.

However, if one assumes that the underlying system doesn’t have a single equilibrium state, but can exist in multiple states, then Holling or ecological resilience is the relevant concept for politics.

Research shows that the majority natural and socioeconomic systems exist in multiple states. This suggests that policymakers should deal with resilience within the sense defined by Holling.

One lake, three states

This is all pretty abstract. To see the way it looks in practice, consider a lake.

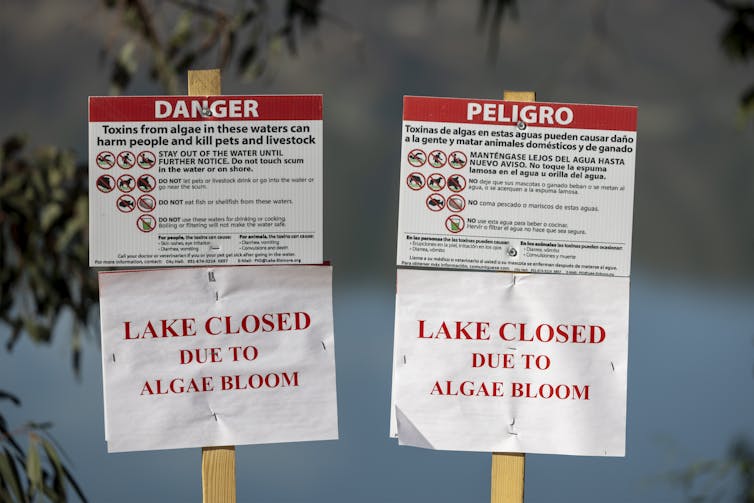

David McNew/Getty Images

Research shows that many lakes can exist in considered one of two stable states, depending on the quantity of the chemical called phosphorus they contain.

For humans, the oligotroph The condition during which the water has underwater vegetation and allows swimming and water sports is the nice condition.

The eutroph The eutrophic state – where nutrients within the water cause turbidity and toxic algal blooms – is the bad one. But that's only from a human perspective. From the algae's perspective, the eutrophic state is nice – and it's stable.

There can be a transient transition state between these two. Show evidence that this three-state classification will also be used to explain many other ecosystems.

The aim of the policy ought to be to maintain the lake within the oligotrophic state for so long as possible or, alternatively, to maintain it within the eutrophic state for as short a time as possible.

In other words, policymakers should aim for the lake to have maximum holling resilience within the ‘good’ oligotrophic state and minimum holling resilience within the ‘poor’ eutrophic state.

Lessons for systems management

Here are three key takeaways:

First, the concept of resilience – because it is inextricably linked to the state of a system – good or badIt all relies on the state of the system that a policymaker desires to influence.

Second, it shouldn’t be very helpful to speak in regards to the Pimm or the technical resilience of the lake, because the lake – and lots of other systems – are in greater than a stable state. This raises the query of how quickly a shocked system returns to its equilibrium state, which can’t be answered meaningfully since the system may not return to its pre-shock state after the shock is removed.

Finally, maintaining our lake in an oligotrophic state comfortable for humans for so long as possible directly brings time into the management problem. Since sustainable development and sustainability are each about dynamics or phenomena that occur over time, there may be a unique connection between resilience and sustainability.

Specifically, the sustainability of a system requires that this technique is resilient in Holling's sense. We could also say that a mandatory condition for the sustainability of a system is that it’s resilient. This can be what the researcher Charles Perring in mind when he says that A development strategy shouldn’t be sustainable if it shouldn’t be resilient.

Environmental policymakers like to speak about sustainability and resilience, but in my experience not enough of them know what these words mean. To achieve higher results, they’ll start by defining the terms.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply