It was Saturday afternoon, and Simonetta led me from the open front door of her home in southeast Chicago into her lounge and sat down on the couch next to her husband, Christopher.

In the Nineteen Eighties, Christopher worked a couple of blocks away at US Steel South Worksearned 3 times the minimum wage and had a highschool diploma – good enough to purchase a house near Simonetta’s parents before her first baby got here. As her neighbors in Southeast ChicagoSimonetta and Christopher's expectations of labor and residential were determined by the steel industry.

Between 1875 and 1990, the roles offered here provided eight steelworks created a dense network of working-class neighborhoods on the marshland 15 miles south of downtown Chicago. For the tens of 1000’s of staff who lived and worked on this region, steel was a rare form of work: unionized blue-collar jobs that paid middle-class wages, with starting salaries within the Sixties of nearly 3 times the minimum wage.

Opportunities for advancement, advantages and job security enabled staff to purchase homes, shop at local stores and construct savings. The steel industry was greater than just work; it organized the spatial and social relations of this district.

H. Michael Miley via Flickr, CC BY-SA

The collapse had devastating consequences for the people within the neighborhood, Simonetta told me. One mill after one other closed In the last twenty years of the Twentieth century, people began to maneuver away from the economic crisis in southeast Chicago to search out latest work – mainly within the service sector.

As we stared on the silent street, I asked them, “Why did you stay?”

Christopher paused, then said simply, “We had the building.” The three-story townhouse belonged to the couple after many years of paying off the mortgage. Sure, it had some crumbling corners and the roof had sagged, however it was theirs. Those 4 partitions remained stable during and after the tumultuous years of economic collapse. That constructing was greater than only a type of equity or material space, it was the muse of their stability.

Why do people stay in difficult places?

In the last 10 years I asked why people stay if their local economy collapses.

My 2024 book states: “Who we’re is where we’re: Finding a house in America's rust belt“I used ethnographic research and interviews to look at the long-term effects of deindustrialization in a rural iron mining community in Wisconsin and in urban manufacturing districts surrounded by Chicago's steel mills.

The causes of deindustrialization were macroeconomic and global – technological change, trade agreements, environmental regulations and increased competition – however the impact was local. In the second half of the Twentieth century, towns and communities that had developed around iron mining and steel industries suddenly lost their core jobs.

AP Photo/Ed Maloney

The Rust Belt region stretches from New York to Minnesota and has experienced five many years almost double-digit unemployment rates. As a result of commercial closures, lots of of 1000’s of individuals are unemployed packed their houses and sought their fortune in factories or mines within the American South or anywhere else where there was not an economic depression. As a result, these deindustrialized places not only lost their inhabitants, but their place in American history economic progress, growth and resilience.

But not everyone goes.

For this study I spoke to greater than 100 peoplelike Simonetta and Christopher, to know why people stay in these neighborhoods when jobs disappear and businesses close. They repeatedly argued that being stuck in them offers them stability in a chaotic world.

Home ownership: a trap and a strategy to keep it

The people I spoke with often began their stories with a practical – and economic – concern: the funds and freedoms of homeownership.

For many long-term residents, moving elsewhere was impossible as a consequence of financial constraints. Low property prices meant they may not recoup their investment by selling, and moving itself is pricey. However, additionally they argued that owning a house offered them a little bit of stability throughout the early years of unemployment.

Good wages and government-subsidized home loans made it possible for staff within the iron and steel industry to buy their very own homes within the mid-Twentieth century.

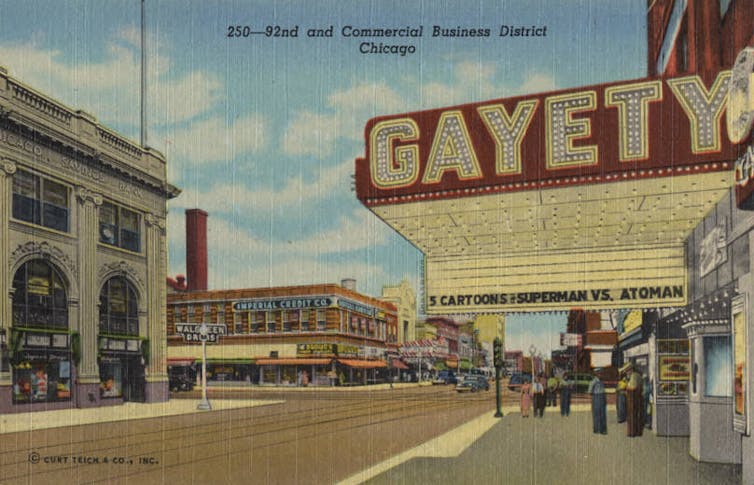

Digital collection of the Curt Teich Postcard Archive (Newberry Library) via Wikimedia

Starting within the Sixties, Southeast Chicago modified from a predominantly renter-occupied area to an area where between 60 and 70 percent of the homes HomeFor Christopher, Simonetta and 1000’s of their neighbors, buying a house was a sound financial decision and a strategy to achieve the American middle class's goal of constructing wealth through private real estate ownership.

Of course, homes are greater than mere material investments. Simonetta and Christopher's home was also their family history. Simonetta's parents had immigrated from Mexico in the primary half of the Twentieth century. Christopher's grandparents had immigrated from Mexico on the turn of the century. Simonetta explained that since they grew up within the neighborhood, once they married they desired to buy a house inside walking distance of her parents and their network of aunts, uncles and cousins.

Jamie Kelter Davis/For The Washington Post via Getty Images

When they made the down payment in 1980, they benefited from falling real estate prices. Wisconsin Steel had just closed its nearby plant, and real estate prices in the encompassing neighborhoods were already down by 9%However, they didn’t expect that the true estate bubble would burst throughout the region.

Real estate prices in your neighborhood began to fall when US Steel slowly laid off staff within the Nineteen Eighties and Nineties. Even today, the typical price for homes in southeast Chicago is between $80,000 and $100,000, lower than a 3rd The median value in Chicago is $330,000.When the neighboring mill closed, their family networks were stuck.

Simonetta recalled: “My father and my parents still lived in the neighborhood. They didn't want to go anywhere. Where would they go?” She continued: “We're not rich. I mean, the factory is closed. We were unemployed!”

Amanda McMillan-Lequieu, CC BY-ND

Even if her parents desired to sell their house and begin a brand new life somewhere more promising, the economic freefall of deindustrialization would have made it too expensive for them to sell. Mass unemployment turned houses that were once solid financial investments into almost unsellable liabilities.

What's the purpose of staying at home?

Even though the economic opportunities of homeownership were limited, owning a property was also a shelter when every little thing else was in turmoil. “The building,” as Christopher called their house, made their path forward easy: They earned money doing odd jobs and commuting over an hour to the suburbs, and so they looked out for one another.

Home can be where family, socially constructed identities and familiar experiences merge. The people I spoke with drove me to their favorite lakes and parks, drew maps to their favorite shops or climbing trails, and identified historical markers of the commercial past. They celebrated the social networks that also anchored their identities – prolonged families, annual parades, and regular school and work reunions.

Interviewees were quick to confess that the broader crisis of deindustrialisation limited their decisions and restricted their options. Yet inside the fragmented framework of post-industrial social life, a generation of long-term residents still belongs together.

“We survived, and that's why we didn't leave,” Simonetta said. “The community has changed, but where else are we supposed to go? I mean, we've been here for over 50 years. … This is my neighborhood.”

“That’s how you destroy neighborhoods,” Christopher interjected, “by leaving!”

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply