Course title:

Science fiction as mental history

How did the concept for the course come about?

For most of its history, science fiction was a disreputable, irrelevant genre. But sources of culture and thought are usually not only present in classical literature or within the writings of the good thinkers. They can be present in the entertainment industry: in movies, comics, pulp fiction and on television.

Big ideas often are available in chunks with labels like “the future,” “technology,” or “freedom.” And most ideas about these items are shaped by science fiction.

In this course, my students explore how the theories of Charles Darwinare reflected, for instance, in science fiction reminiscent of “Jurassic Park”, “The Island of Dr. Moreau”, “X-Men” And “The Wrath of the Khan.”

I’m fortunate to be a part of the third generation of professors to show this course at Auburn. It is an old, established subject that I inherited here.

What does the course examine?

I normally select three big plot ideas from science fiction: alien encounters, time travel, and superhuman abilities. Then we follow the event of those ideas, mainly through American fiction.

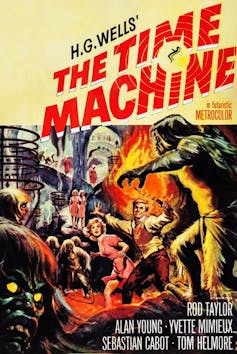

Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images

Students could read HG Wells' “The time machine”, written within the Nineties and telling the story of the Eloi and Morlocks, posthuman races from 800,000 years in the long run; CL Moore's secret visitors from the long run within the 1953 novella “Vintage season”; and Steven Spielberg’s escape into the idealized Fifties in 1985’s “Back to the future.”

These works all contain confusing theories about what time travel might appear like, but students will even see that every of them tells a distinct story concerning the fears and obsessions of the time during which they were created.

Wells' novel, for instance, is a vision of how hundreds of years of Victorian class divisions led to the event of a bunch of cannibalistic underground people. In Back to the Future, Marty McFly leaves the dingy, seedy Nineteen Eighties for a clean and glossy version of the Fifties that appears far more promising than 1985. The film takes the Nineteen Eighties political and cultural nostalgia for so-called “simpler” times. (Of course, of their 1955 version, Biff and Marty never take care of racial segregation or the nuclear panic of the Cold War.)

Science fiction offers a sort of film negative of history – a back door to what worries or frightens people, reasonably than to what was heroic. Science fiction captures that fear and anxiety.

Rod Serling's 1960 episode of The Twilight ZoneThe monsters come to Maple Street“” is the story of how neighbors attack one another when they believe an alien invasion. It runs parallel to the American crisis of desegregation and communist subversion.

Serling concluded,“Let's be clear: prejudice can kill and distrust can destroy, and a thoughtless, fearful search for a scapegoat has its own consequences – for the children and the unborn. And the sad thing is that such things cannot be confined to the Twilight Zone.”

Why is that this course relevant now?

New technologies and infinite Predictions And Prophecies concerning the future, bombard the scholars.

It's necessary to pause for a moment and step back. How is the best way we speak about and use technology influenced by how we were raised to take into consideration technology and the long run? And to what extent do past visions of the long run dictate the selections we make in the current?

What is a crucial lesson from the course?

Students often think that technology has rules and follows those rules. But that’s not how technology works.

This is each frightening and inspiring since it implies that we will still shape and picture our future exactly as we would like it to be.

What materials does the course contain?

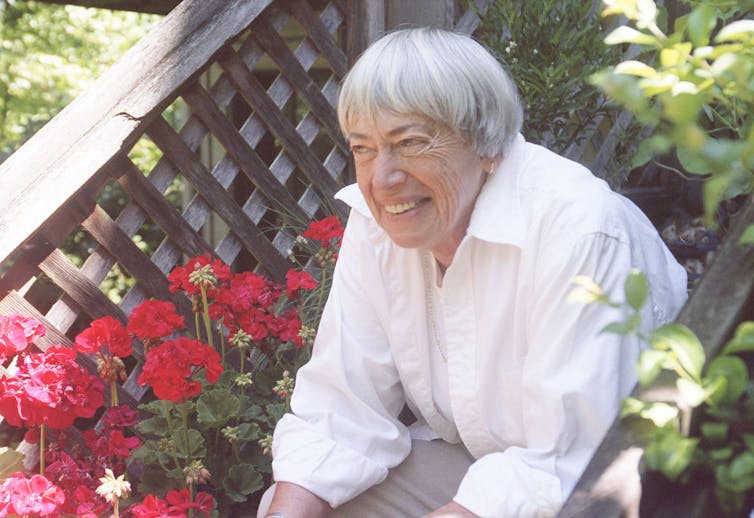

I anchor the course with a series of novels; the list changes, but it surely all the time includes “The Time Machine” and Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1971 novel “The Lathe of Heaven.”

In addition, I try to incorporate a mix of pulp stories, television series, radio plays, comics and movies. I classify the avant-garde science fiction stories of the Seventies Brian Aldiss And Joanna Russand underground literature from the Nineteen Eighties, reminiscent of the graphic novel “Ed, the happy clown.”

Beth Gwinn/Getty Images

I design the course like a standard “great books” courses—which showcase the works of mental and literary greats—by assigning a distinct work each week. I just have a distinct idea of what makes an important book.

We also spend a beautiful week examining the economic and cultural history of “so bad it’s good” B-movies and late-night movies, during which I watched an episode of the Canadian science fiction series “The Lost Star”, is taken into account one in every of the worst shows in television history. Sometimes you could have to learn what to not do.

What does the course prepare students for?

They learn to read and think. They learn that each one stories are based on ideas and philosophies, whether easy or complex, clever or silly.

I hope they learn to look at out for nonsense in public debates about technology and the long run – as some people assume, computer modelling because human language is identical as language – and listen to Ideologies disguised as motion movies.

I hope they learn to like an creator they've never read before – and appreciate how much reading and stories make life value living.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply