Rabies is a fatal disease. Without vaccination there’s a risk of rabies infection 100% deadly as soon as someone develops symptoms. Texas has experienced two epidemics of rabies in animals since 1988: one with coyotes and dogs in south Texas and the opposite with gray foxes in west central Texas. These outbreaks, which affected 74 counties, resulted in hundreds of people that might have been exposed to the virus, two human deaths, and countless animal lives lost.

In 1994, Governor Ann Richards declared rabies a state health emergency. The Texas Department of State Health Services responded by introducing the Oral rabies vaccination program to manage the spread of those rabies outbreaks in wild animals.

The program has been distributed since 1995 over 53 million doses of rabies vaccine across 758,100 square miles (almost 2 million square kilometers) in Texas by hand or plane. The variety of rabies cases in dogs and coyotes increased from 141 to 0 by 2005, and the variety of rabies cases in foxes increased from 101 to 0 by 2014. By 2004, there was a variant of rabies in dogs effectively eliminated from Texasand one other variant has been largely controlled.

We are researchers who’ve began Study of untamed animal rabies And oral vaccination within the Eighties. From providing a proof of concept for using oral vaccines in raccoons to being among the many first to make use of latest rabies vaccines within the Nineties, we’ve got been on the forefront of efforts to contain this deadly virus.

Decades of vaccine research resulted in one of the vital successful public health projects in Texas. And we hope it could provide a roadmap for deploying mass vaccinations in wildlife to forestall future outbreaks.

Rodney E. Rohde/Texas DSHS Zoonosis Control Division.

Development of the oral rabies vaccine

The Texas Oral Rabies Vaccination Program has benefited greatly from the work of several researchers over the past few many years.

There were several within the mid-Twentieth century major developments in combating rabies. Virologists and veterinarians report that attempts to poison or capture infected animals have failed George Bear on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognized the necessity for a distinct strategy to forestall and control rabies in wildlife. His and his colleagues' work within the Nineteen Sixties led to the concept of oral rabies vaccination. While oral vaccination of untamed animals would help combat the infection at its source, it was previously considered logistically unfeasible as a result of the massive range of goal animals.

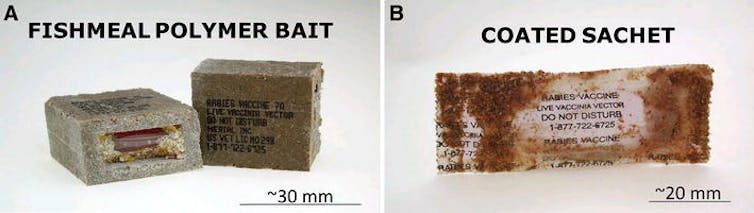

European researchers began doing this within the late Nineteen Seventies first field tests Orally vaccinate foxes against rabies. Small plastic containers were full of vaccines and inserted into bait like chicken heads. Over 50,000 of those vaccine-laden baits were distributed in fox habitats in forests and fields over a four-year period.

Maki et al/Veterinary Research, CC BY-ND

Researchers in Canada also began similar field trials in Ontario. In the Eighties, a median of 235 rabid foxes per 12 months were reported in the world. From 1989 to 1995, oral rabies vaccine baits were used annually, successfully eliminating the fox variant of rabies throughout the world.

Recombinant oral rabies vaccine

The first generation of those vaccines used live viruses modified in order that they don’t cause serious illness. Although effective and usually protected, the unique rabies vaccines required storage at cool temperatures and carried the rare risk of causing rabies in animals.

In the early Eighties, scientists developed recombinant rabies vaccines that use a separate virus to specific the rabies virus genes. A collaboration between a non-profit institute, the US government and the pharmaceutical industry led to the event of a recombinant virus vaccine which produced a rapid immune response against rabies without the potential for causing rabies.

In 1984 Preliminary work on laboratory animals showed promise of using an oral type of the recombinant vaccine to vaccinate animals. However, the concept of using genetically modified organisms was still in its infancy, each in science and amongst most people. While the vaccine was protected and effective in captive raccoons and foxes, big questions emerged about how it would affect other species once released into the environment.

Rodney E. Rohde/Texas DSHS Zoonosis Control Division.

After years of labor improving the design of the vaccine and testing its safety in multiple non-human species, the first European attempt took place at a military base in Belgium. Because there was data showing that the vaccine could safely and effectively control wildlife in Luxembourg and France, it was approved in 1995 to combat fox rabies.

Similar studies of the oral recombinant rabies vaccine have been conducted within the United States. The first trial began in 1990 Parramore Island off the coast of Virginiaand a 12 months of intensive monitoring revealed no significant negative impacts on the environment or wildlife species. A second year-long study on the mainland near Williamsport, Pennsylvaniahad similarly positive results.

After the vaccine was successfully utilized in tests to combat raccoon rabies in several other east Coastal statesIn 1997 it was approved to be used on raccoons.

In 1998, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service received funding expand existing oral wild vaccination projects to states of strategic importance to forestall the spread of certain rabies viruses and to coordinate interstate projects.

Results in Texas

In Texas, the oral recombinant vaccine is now distributed primarily by hand and thru about 75 separate helicopter flights per 12 months.

The Texas Department of State Health Services rabies lab worked with the CDC to develop this Regional reference typing laboratory for rabies viruses. One of us was recruited to each distribute and develop the vaccine locally Molecular typing tools to tell apart between various kinds of rabies virus variants within the laboratory. Using these techniques, we were in a position to determine where different variants of the rabies virus were occurring at any time limit.

Our lab was also the primary within the country outside of the CDC to assist other U.S. states and countries test their samples for rabies virus variants. These techniques helped researchers monitor where rabies epidemics continued or declined as a result of wildlife vaccinations latest types of distribution.

Given the constant threat of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases comparable to COVID-19 and influenza, the prospect of mass vaccination of wildlife might be a strategy to combat future pandemics. Although there continues to be a variety of work ahead of us, we hope that at some point we may have the chance to achieve this through mass vaccination of untamed animals to scale back or eliminate infectious diseases comparable to rabies.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply