When modern Americans call themselves patriots, they’re remembering a sentiment that’s 250 years old.

In September 1774, almost two years before the Declaration of Independence, delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies gathered within the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. They quickly developed a political, economic and cultural program to unite the so-called “patriot” movement against British rule.

As Smithsonian Institute curator researches American identityI examine the often-forgotten ways by which the First Continental Congress mobilized unprecedented numbers of colonists around common goals. Perhaps most significantly, it established crucial terms by which contemporaries measured patriotism—and identified nonpatriots—within the early years of the Revolution.

The delegates met to cope with a direct crisis. The British Parliament had recently passed a series of measures expressly intended to punish the colonies for the destruction of tea in Boston Harbor by the Boston Tea Party.

The so-called Unbearable acts forced closure of the Port of Bostonthe representative bodies of the Government of Massachusetts and provided Quartering of troops in any of the colonies without the consent of their legislatures.

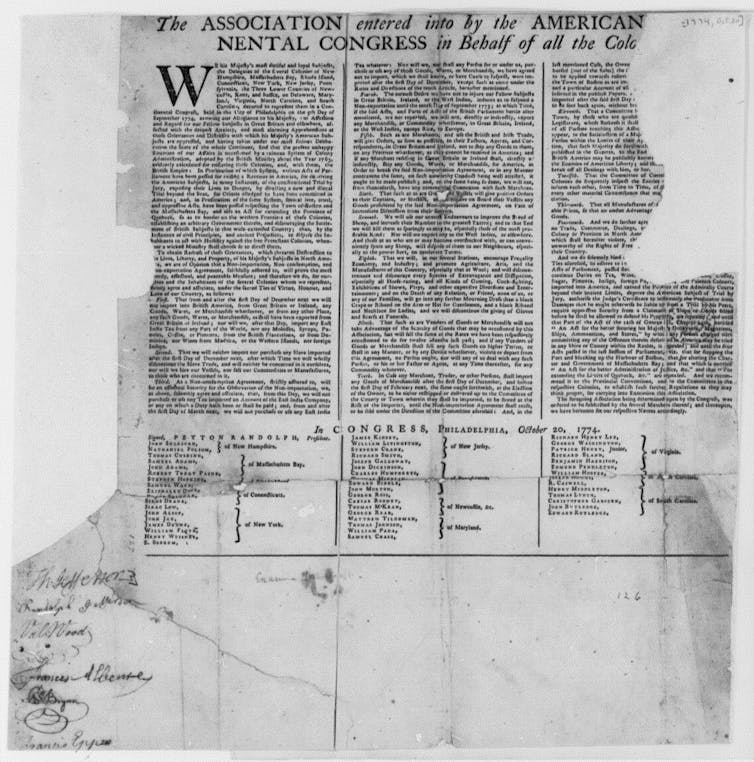

Taken together, these measures mean “threaten to destroy the lives, liberty and property of His Majesty’s subjects in North America”, the delegates wrote to Congress. They quickly proposed the “most prompt, effective and peaceful measure” they may imagine to counteract the British penalties – a “non-import, non-consumption and non-export agreement”, called “Continental Association.”

Building on earlier efforts to limit trade with Britain, which had been undertaken by various colonies or port cities, Congress now went a step further, declaring a comprehensive trade boycott for all 13 colonies and calling on all supporters of colonial rights from New Hampshire to Georgia to just accept the restrictions.

Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

New economic connections

The Continental Association called on all American merchants to stop importing British manufactured goods as of December 1, 1774, and called on all American consumers to refuse to buy such products.

There can be no more positive silk, no more Irish linen, no more Indian cotton; no more fashionable accessories corresponding to decorative ribbons and lace, parasols or fans. Americans wouldn’t buy European paints, ironware or furniture; no more molasses or coffee from the West Indies, and naturally no more East Indian tea. The import of such goods had put the colonies into debt.

The agreement also banned events that involved luxury consumption, corresponding to theater visits, meetings and balls, horse racing and other expensive entertainment. It even modified the funeral rituals by Ban on imported mourning clothes and expensive silk gloves which the bereaved often presented to the mourners at these ceremonies.

Just as necessary, the Continental Union encouraged domestic production within the colonies to exchange goods previously purchased from Britain. It discouraged the consumption of lamb to extend wool supplies for colonial cloth manufacture. It relied on urban artisans and peasant households – women in addition to men – to extend their production and replace other English goods that were now banned.

The idea was to create recent trading networks throughout the colonies, replacing the colonists' dependence on Britain with mutual dependence. Wealthy consumers would now support their manufacturing neighbors – and thus put money of their pockets – by buying homespun cloth, herbal teas, and other goods made in America. Finally, the Continental Union prohibited merchants from raising prices on English goods once they became scarce.

The Continental Association made clear the terms of so-called “patriot” behavior: a supporter of American rights would forgo British imports, promote American-made goods, and forgo undue business profits.

Anyone who violated the terms of the pact was branded an “enemy of British American rights.”

National Museum of American History

mobilization

Even as Congress adjourned, supporters of the proposed program took motion. Voters in cities, counties, and seaports began electing committees to implement Continental Union.

To ensure community cohesion, some communities elected political nobodies as representatives alongside established leaders. Ordinary men and even women, who as widows were sometimes the heads of the household, began to sign written copies of the agreement.

Beginning on December 1, 1774, the brand new trade rules provided a public panorama of economic and political activity in marketplaces, on harbor quays, and at meetings in courthouses, meeting houses, and taverns. Committee members searched merchants' warehouses for prohibited goods and questioned suspected contract violators. They published the names of the unrepentant in the general public newspapers – often as a signal to “friends of their country” to stop all business with these contract violators, who were now considered “enemies” of American liberty.

In the months that followed, newspapers printed reports of the committee's decisions, but in addition rumors, accusations, apologies, and reports of crowds confronting unruly merchants or incorrigible tea drinkers.

Colonial readers learned, amongst other things: A public meeting in Gloucester County, Pennsylvania, called for the Association to be enforced as if it were “enshrined in law.” A merchant named John Armstrong on the Isle of Wight, Virginia, regretted violating the Association and now promised reforms. Blacksmiths in Worcester, Massachusetts, vowed to not do work for non-members of the Association. Women in Hartford, Connecticut, gathered to spin yarn that weavers could use to make cloth for the poor. A tea merchant in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, apologized for selling tea and even publicly burned his supply of tea. A Philadelphia alderman was buried in the only of funerals—conducted strictly in keeping with Continental Association regulations.

Because editors frequently reprinted news from other newspapers, readers could see their fellow patriots at work even in far-flung colonies. Readers within the Carolinas, for instance, could feel solidarity with like-minded colonists in New Hampshire or New York.

“One People”

The cumulative effect of this broad public mobilization is, for my part, already evident in the primary sentence of the Declaration of Independence. In July 1776, the Second Continental Congress described the inhabitants of the 13 colonies as “a people”, quite able to asserting independence from “another” people – the British on the opposite side of the Atlantic.

In my view, the experience of the Continental Union of 1774 played a vital role within the formation of the 13 colonies into such a “one.” Certainly it helped persuade Americans of various regions, interests, backgrounds, and beliefs that they may act as patriots by moving beyond their differences to pursue a typical interest. They had already joined together, because the First Continental Congress put it: “in alliance with virtue, honour and love for our country.” Perhaps there’s something there price remembering today.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply