Children born worldwide in 2020 will experience twice as many forest fires over the course of their lives in comparison with those born in 1960. In California and other western states, frequent wildfires are as much a component of summer and fall as popsicles and candy on Halloween.

Forest fires produce high-quality particulate matter, or PM₂.₅, which suffocate the air and penetrate deep into the lungs. Researchers know that short-term exposure to PM₂.₅ from forest fires can Acute care visits for cardiovascular problems reminiscent of asthma. However, the long-term effects of repeated exposure to PM₂.₅ from wildfires on chronic diseases are unclear.

One reason for that is that science has not yet reached a consensus on how best to measure this sort of temporary but sustained stress. Environmental epidemiologists And Health Scientist Like us, we typically aggregate long-term exposure to total PM₂.₅ – which comes from power plants, industry and traffic – as a mean exposure over a yr. This is probably not useful when measuring exposure from wildfires. Unlike, for instance, traffic-related air pollution, PM₂.₅ levels from wildfires fluctuate widely over the course of the yr.

To improve health and justice research, our team developed five metrics which higher capture the long-term impact of forest fire PM₂.₅.

Measuring fluctuating PM₂ levels during forest fires

To understand why current measurements of PM₂.₅ from wildfires don’t adequately capture a person's long-term exposure, we’d like to take a look at the concept of averages.

Suppose the common PM₂.₅ level over a yr is 1 microgram per cubic meter. An individual may very well be exposed to 1 microgram per cubic meter each day for one year, or 365 micrograms per cubic meter on a single day.

Although these two scenarios end in the identical annual average exposure, they could have very different biological effects. The body may give you the option to fend off damage from a each day exposure of 1 microgram per cubic meter, but could also be overwhelmed by a single, huge dose of 365 micrograms per cubic meter.

To illustrate: In 2022, Americans experienced a average total pollution by PM₂.₅ of seven.8 micrograms per cubic meterResearchers estimated that within the 35 states where wildfires occur, these wildfires only burn a mean of 0.69 micrograms per cubic meter However, this attitude is simply too short-sighted, as a complete of PM₂.₅ will likely be released annually from 2016 to 2020.

For example, in a census tract near the 2018 Camp Fire, a mean PM₂.₅ concentration from wildfires of 1.2 micrograms per cubic meter was recorded between 2006 and 2020. However, throughout the actual fire event, the height concentration was 310 micrograms per cubic meter – the highest level worldwide on today.

Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images

Scientists want to raised understand what such extreme stress means for human health in the long run. Previous studies Long-term PM₂.₅ exposure from wildfires focused totally on people living near a big fire and examined their health status years later, excluding any recent exposures that occurred between baseline and follow-up.

Recent studies have examined long-term exposure to wildfire PM₂.₅, which changes over time. For example, researchers reported associations between exposure to wildfire PM₂.₅ over two years and the danger of death from cancer and other causes in Brazil. This work was also based on long-term average exposure and extreme exposures from periodic wildfire events were in a roundabout way measured. Because the study didn’t assess this, we have no idea whether a selected pattern of long-term PM₂.₅ exposure from wildfires was more harmful to health.

Most days, people are usually not exposed to wildfire particle pollution. However, some days, wildfire pollution could be very high. We currently have no idea whether just a few very bad days or many barely bad days pose a greater health risk.

A brand new framework

How can we arrive at more realistic estimates that capture the big peaks in PM₂.₅ levels that folks are exposed to during wildfires?

When it involves the particulate matter exposure people experience from wildfires, exposure scientists—researchers who study contact between people and pollutants within the environment—consider frequency, duration, and intensity. These interlocking aspects help describe the true burden on the body during a wildfire.

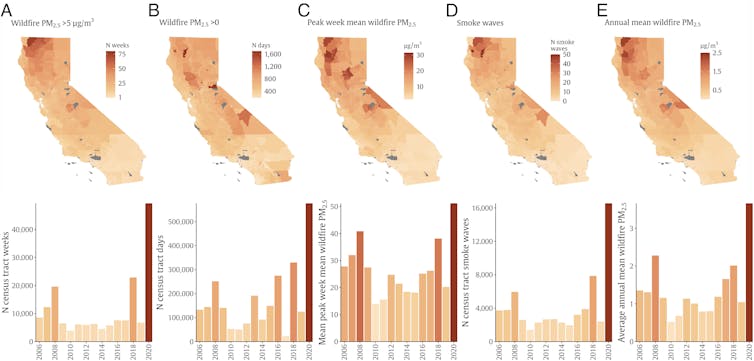

In our recent study, our team suggested a Framework for measuring long-term exposure to wildfire PM₂.₅ that takes under consideration the frequency, duration, and intensity of wildfires. We applied air quality models to California wildfire data from 2006 to 2020 and derived recent metrics that capture a spread of exposure types.

Casey et al. 2024/PNAS, CC BY-NC-ND

One metric we’ve developed is the variety of days with wildfire PM₂.₅ pollution over a protracted time frame, which may discover even the smallest pollution. Another metric is the common concentration of wildfire PM₂.₅ throughout the week with the best smoke pollution over a protracted time frame, which highlights the locations with the best pollution. We have also developed several other metrics which may be more useful depending on the impacts being studied.

Interestingly, these values were highly correlated with one another, suggesting that on many days there was no less than some amount of PM₂₅ in wildfires. had the best values overallWhile this may occasionally complicate the choice making between different exposure patterns, the appropriateness of every measure depends partly on the health effects we’re studying.

Environmental injustice

We also examined whether certain racial and ethnic groups were exposed to above-average levels of high-quality particulate matter from wildfires. We found that different groups were most in danger depending on the yr.

Consider 2018 and 2020, two years of major wildfires in California. The census tracts most affected by any measure were primarily non-Hispanic whites in 2018 and Hispanics in 2020. This is sensible, since non-Hispanic whites make up about 41.6% of California's population and Hispanics make up 36.4%.

To understand whether other groups were exposed to excess exposure to wildfire PM₂.₅, we made relative comparisons. That is, we compared the actual exposure to wildfire PM₂.₅ of every racial and ethnic group to what we might have expected in the event that they had been exposed to the national average.

We found that Indigenous communities were most exposed, exposed to 1.68 times more PM₂.₅ than expected. In comparison, non-Hispanic white Californians were exposed to 1.13 times more PM₂.₅ than expected, and multiracial Californians were exposed to 1.09 times greater than expected.

Eric Thayer/Stringer via Getty Images News

Rural tribal areas had the best average PM₂.₅ concentrations from wildfires – 0.83 micrograms per cubic meter – of all census tracts in our study. A big portion of Native Americans in California live in rural areas, often with higher forest fire risk resulting from a long time of poor forest management, including the legal suppression of cultural slash-and-burn practices, which studies have shown Help reduce catastrophic wildfires. Recent State laws has eliminated liability risks related to cultural fires on indigenous lands in California.

Understanding the causes and health effects of high long-term exposure to wildfire PM₂.₅ amongst Native Americans and Alaska Natives might help significant differences in health between these groups and other Americans.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply