Donald Trump's efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election not only failed, but were also based partly on a misinterpretation of the U.S. Constitution. as our recent evaluation arguesThe corresponding constitutional provision dates from the period immediately after the Civil War and was recognized by contemporaries as a central protective mechanism of American democracy.

In November 2020, when it became clear that Trump had lost the favored vote and would lose the Electoral College, Trump and his supporters organized a Print campaign to steer the legislatures of several states whose residents voted for Joe Biden to appoint electors who would support Trump's re-election within the Electoral College vote.

Trump and his allies contacted Republican lawmakers in Michigan, Georgia and Pennsylvania to State parliaments to overturn the end result of the favored vote. Ginni Thomas, the wife of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, via email to GOP lawmakers in Arizonaand called on them to “ensure that a clean slate of electors is elected.”

These efforts were based on a provision of the Constitution in Article II, Section 1, which states: “Each State shall appoint in the manner prescribed by the legislatora number of electors.” Trump and his supporters wanted state legislatures to discard their residents’ votes and easily appoint electors who would support Trump’s re-election campaign.

As a part of their efforts, Trump and his supporters claimed that the Constitution allows state legislatures to directly elect an inventory of electors and not using a referendum.

But they were improper. There was already a safeguard in place – and it still exists today – to forestall this approach from getting used to undermine the 2024 presidential election.

An try and protect the facility of the voters

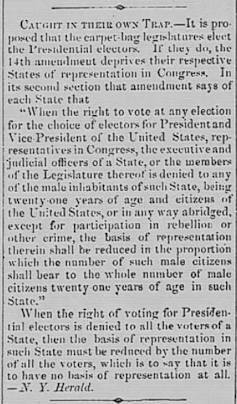

The Anderson Intelligencer via newspapers.com

In just about all states Candidate who receives probably the most votes For the presidency, the candidate receives all of the votes of the electors of the respective state. Nebraska and Maine have small exceptions – but under the laws of those states, nearly all of electoral votes still go to whoever receives nearly all of votes nationwide.

In the late 1860s, when the 14th Amendment was drafted and ratified, the identical was true – although the proper to vote limited to men until 1920and states often denied or restricted the proper to vote for some residents, particularly members of ethnic minorities. After the Civil War, Congress attempted to cut back barriers to voting for black men, particularly within the South.

When Congress debated the 14th Amendment in 1866, its drafters drafted Section 2 in a Efforts to force reluctant white Southerners to grant black men the proper to vote.

Section 2 of the 14th Amendment states: “if the right to vote in every election for choosing Electors for President and Vice President of the United States … is denied … or in any manner abridged …, the basis of representation” for that State within the United States House of Representatives “shall be reduced” in proportion to the quantity of the abridgement.

So if a state were to deprive one in all its residents of the proper to vote, it might immediately lose the identical percentage of seats within the House of Representatives as a percentage of people that were disenfranchised.

Just just a few weeks after ratification, this provision was questioned for the primary time.

The Republican-dominated Reconstruction Legislature of Florida decided to carry presidential elections without popular vote. The Democrats—then the party that supported black disenfranchisement—were furious. Many Southern newspaper journalists, still indignant concerning the ratification of the 14th Amendment, saw a chance to show the amendment against its Republican authors.

“The easy conclusion is that if in a state “If the choice of Presidential Electors is no longer left to the people, and placed in the hands of the Legislature, the whole citizenry of the State… will be excluded from it,” wrote the Charleston Daily News on August 10, 1868.

This was not a rare or local view: nine days later, the Anderson Intelligencer, a South Carolina newspaper, published a brief article attributed to the New York Herald that stated similarly:

“If all voters in a state are denied the proper to decide on presidential electorsthen the premise of representation on this state have to be reduced by the variety of all voters, that’s, there must not be any basis of representation in any respect.”

These opinion pieces don’t have any legal authority, but they reflect a standard – albeit controversial – Understanding the provisions of the 14th Amendment on the time of its passage. No one filed a lawsuit, so no court had the chance to comment. And the Republican-dominated Congress had no qualms about accepting electoral votes – even and not using a popular vote – for the Republican presidential candidate.

The right to have your vote counted

After the 2020 election, Congress took steps to make clear that electors have to be those who select presidential electors. A law passed in 2022 revised the federal law governing electoral college selection to require state legislatures to find out their state's method for choosing electors before Election Day and can not change it after the votes have been forged.

This clarification is consistent with, and even strengthens, the provisions of Section 2 of the 14th Amendment.

As our evaluation shows, a direct election of electors by a state legislature would disenfranchise all voters within the state. After all, the proper to vote is the proper to have one's vote counted, not the proper to have one's candidate win.

Thus, even when the legislature were to pick out a slate of electors that might have received significant support in the favored election, the legislature's decision would limit the rights of each voter within the state. Disenfranchisement is determined by whether the people or the legislature selects the electors, not on which electors are chosen.

If all voters in a state are disenfranchised, Section 2 requires that the The state’s representation within the House of Representatives will probably be immediately and mechanically reduced to zero. The Constitution elsewhere provides that the representation of every state within the Electoral College Total of the delegations of the House of Representatives and the Senate of the State.

If a state doesn’t have a representative within the House of Representatives, it might only have two electors, making its influence on the presidential election negligible and largely irrelevant.

A single exception

To date, it’s the only case, other than Florida in 1868, during which a state legislature has chosen its presidential electors and not using a popular vote. got here in 1876.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Electoral fraud, political violence and voter intimidation undermined the integrity of the 1876 presidential electionThe Constitution of Colorado, which was newly recognized as a state, provided that the legislature In 1876, elect the state's presidential electors and not using a popular voteOvershadowed by an exceptionally bitter election, the number of Colorado’s presidential electors by the legislature relatively little attention or debate.

Overall, one can conclude that Southern newspapers in 1868 read the text of Section 2 accurately. The authors could have been cynical opportunists looking for to defend an untenable racist hierarchy, but their interpretation of the text is cheap.

The meaning of Section 2 is obvious and provides for severe penalties if a state doesn’t allow its residents to vote for presidential electors. The 14th Amendment continues to guard American democracy greater than 150 years after its ratification.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply