Imagine a bee crawling right into a shiny yellow flower.

This easy interaction is one you’ll have observed repeatedly. It can also be a critical sign of the health of our surroundings – and I actually have observed it in a whole bunch of hours of fieldwork.

Plant-pollinator interactions contribute to plant reproduction, support pollinator species equivalent to bees, butterflies and flies, and profit each agricultural and natural ecosystems.

These one-to-one interactions happen inside complex networks of plants and pollinators.

In my laboratory on University of Colorado Boulderwe’re taken with how these networks change over time and the way they reply to stressors equivalent to climate change. My team emphasizes long-term data collection within the hope of uncovering trends that will otherwise go unnoticed.

Working at Elk Meadow

Ten years ago, I began working in Elk Meadow, which is positioned at 2,900 meters altitude, on the University of Colorado's Mountain research station.

I wanted a location nearby where I could conduct frequent observations to review the dynamics of plant-pollinator networks. This beautiful subalpine meadow, filled with wildflowers and only 40 minutes from campus, was just the proper fit.

Since 2015, I actually have been making weekly hikes to Elk Meadow, often accompanied by members of my lab. We visit the meadow from the primary bloom in May to the last in October. We observe pollinators visiting flowers in plots scattered throughout the meadow and walk along the sting to reduce trampling. Morning is one of the best time to go to because pollinator activity is high and thunderstorms often develop midday within the Rocky Mountains in the course of the summer.

Monitoring the network

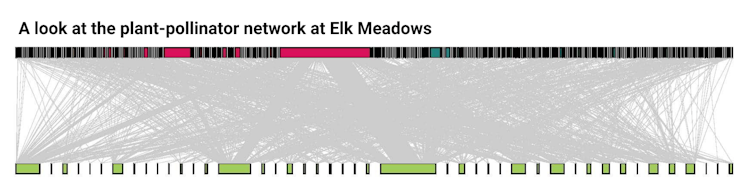

Elk Meadow is wealthy in biodiversity. Over the years, we now have observed 7,612 interactions between over 1,038 unique species pairs. These pairings were formed by 310 pollinator species and 45 plant species.

Resasco Laboratory, CC BY-ND

Pollinators include not only a wide range of bees, but in addition flies, butterflies, beetles and the occasional hummingbird. Experienced entomologists help us discover some insects.

The plants include widespread species equivalent to the common dandelion and a few which are only present in the Rocky Mountains, equivalent to the Colorado columbine.

Common but essential

Collecting data at Elk Meadow is fun, but it surely's also serious science. Our data are useful for understanding the dynamics of plant-pollinator interactions inside and across seasons.

Julian Resasco, CC BY-ND

For example, we now have learned which interactions between plants and pollinators are stable and which change over time and space. We consistently adhered to Interactions between generalist species and their many partners over time and in several plots within the meadow.

Generalist species can tolerate a big selection of environmental conditions, meaning they’re more ceaselessly available for interactions.

In other words, generalist species usually tend to be alive, energetic and foraging (within the case of pollinators) or flowering (within the case of plants) than species that may only survive when environmental conditions equivalent to temperature, sunlight and rainfall are good for them.

Generalist species are essential in networks, but they often don’t receive the identical conservation attention as rare species. Even these common species may decrease on account of environmental changes Destabilization of entire ecosystems. Protecting these species is essential for preserving biodiversity.

In it for the long run

Julian Resasco, CC BY-ND

The more years of knowledge we collect, the more useful our study shall be for understanding how networks and pollinator populations are changing—especially given increasing signs of climate change. Most ecological studies are designed or funded for under one or a number of years, making our 10-year dataset one in all the few for plant-pollinator networks.

Only with long-term ecological data can we discover Trends within the answers to climate change, particularly on account of large annual fluctuations in weather and population.

The National Science Foundation supports a network of Long-term ecological research stations throughout the United States, including the Niwot Ridge Long-Term Ecological Research Program near Elk Meadow, which is devoted to the study of high mountain species and ecosystems.

The climate in Colorado, like in much of the world, Significant changesequivalent to rising temperatures, earlier melting of snow, and more rain in late winter and spring as a substitute of snow. These changes result in earlier runoff of water from mountains, drier soils, and more severe droughts. These shifts can have essential consequences for plants and pollinators, including changes within the distribution, abundance, flowering time of species, or their foraging habits.

Plant and pollinator communities at high elevations could also be particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change because these areas larger temperature increases in comparison with lower altitudes.

We have seen warmer and drier conditions in Elk Meadow. Overlaying this trend, we now have observed annual temperature fluctuations and drought conditions that will help us understand and predict how different species will fare in a warmer and drier future.

Climate change is a driver of pollinator population decline and is predicted to turn out to be much more essential in the approaching a long time. Immediate threats also include pesticide use, light pollution and the Destruction of untamed habitats for Agriculture and Development.

The state of Colorado recently commissioned a study to assess the state of health of Colorado's native pollinators and make recommendations for his or her protection.

Appreciating the present pollinator landscape

Working at Elk Meadow has given my students the chance to conduct independent research and receive priceless training and mentorship.

Seeing the great thing about the creatures within the meadow and observing their cycles inspires my students and me.

Elk Meadow is a spot where I can clear my head and provide you with recent research ideas. It's also a spot where I can observe and record how a tiny patch of our planet is changing in response to larger changes around it.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply