When we went to an aspen forest near Madison, Wisconsin, with a colleague within the spring of 2021, we expected to finalize our plans for a research project on several species of insects that live in and feed on the trees. Instead, we found a forest full of furry, brown egg masses.

These masses, belonging to an invasive species called the gypsy moth, brought our plans to an abrupt end. We knew that hungry gypsy moth caterpillars would eat the forest bare inside weeks.

Richard L. Lindroth

We are chemical ecologists interested in how plant chemistry affects the interactions between plants and herbivorous insects. As experienced scientists, we all know that sometimes good science stories end very in another way than researchers originally expected. This is one in every of those stories. And like many good stories, it involves villains, beauty, poison, and death.

After an initial period of despair over the fate of our aspen forest, we modified our research plans to research how leaf loss – one other word for leaf consumption – by an invasive species might alter the chemical composition of plants to the detriment of native species.

All Plants produce defense substances to ward off herbivores resembling insects that attempt to eat them. These defenses include well-known chemicals resembling tannins, caffeine, and cyanide. Insects, in turn, have evolved adaptations to those chemical defenses which are tailored to the particular species they feed on.

The results of this study surprised even us and published in September 2023 within the journal Ecology and Evolution.

The ecological actors

Aspen () is the most typical tree species in North America.

Richard L. Lindroth

As a keystone species, the aspen provides food and shelter for a lot of forest organisms. Without these trees, forests across much of North America would look very different. The aspen is ecologically successful, partly due to its unique chemistry. It produces a category of Defense substances, so-called salicinoidsUnder most conditions, these defense mechanisms prevent herbivores from completely defoliating trees.

Invasive gypsy moths () are essentially the most destructive defoliators of deciduous forests in North America. Aspen is a preferred food plant of the gypsy mothwhich feed on expanding leaves in early summer. At high population densities, gypsy moths can defoliate large areas of forest.

This carnage brought on by the gypsy moth doesn’t bode well for other insects that rely on aspens for food, resembling the native silkworm, which feeds on aspens from mid to late summer.

Richard L. Lindroth

A natural experiment

From May to June 2021, the caterpillars of the gypsy moth ate almost every green leaf in our aspen forest.

At the start of July, nevertheless, the trees had full leaves again. In a second aspen forest of the identical age, six kilometers away, there was no leaf shed.

Mark R. Ornaments

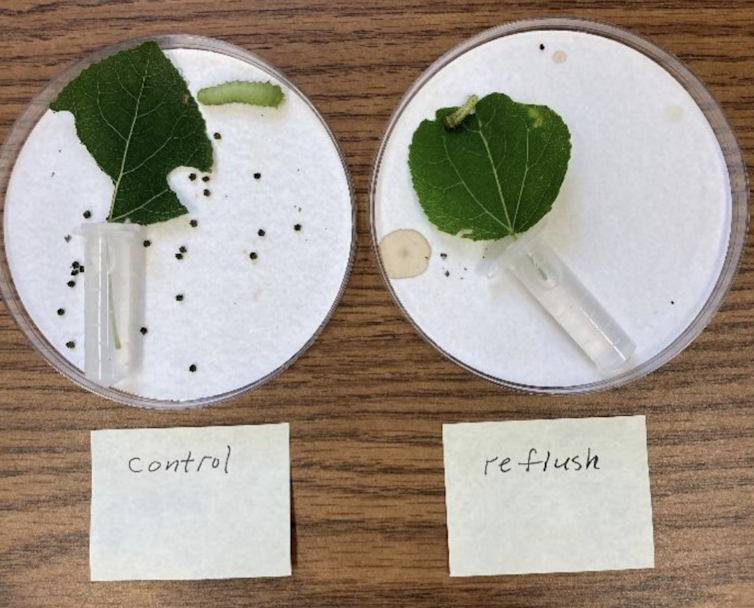

This combination of damaged and undamaged forests provided the proper conditions for what scientists call a natural experiment. The undamaged forests served as an experimental control that we could compare to the damaged forest to evaluate the implications of leaf shedding by the gypsy moth on insects that feed on them in late summer.

We collected leaves from each forests in late summer and analyzed them for his or her salicinoid content.

We also fed the native Polyphemus caterpillars with leaves from the defoliated forest or from control forests to see how the defense substances affected their ability to survive and grow.

We found that After defoliation by gypsy moths, aspens grew a second set of leaves with significantly higher salicinoid levels—on average 8.4 times higher. In contrast, leaves from the control forest had significantly lower salicinoid levels, typical for aspens in late summer.

The high concentrations of defense substances within the defoliated forest caused severe damage to the native silkworm caterpillars. Only just a few caterpillars survived when fed with leaves from the previously defoliated forest. Those that survived showed growth disorders.

Richard L. Lindroth

Ecological impacts

Our research has shown for the primary time how an invasive species can harm a native species by making their shared food source rather more toxic. And one of these ecological dynamic is probably going not limited to only aspen and silkworm caterpillars.

Over 100 different species of insects and mammals feed on aspen trees. our previous research has shown that top concentrations of salicinoids are harmful to lots of them. Other tree species resembling oak also produce more defensive substances after the gypsy moth sheds its leaves, which could affect native herbivores.

Richard L. Lindroth

Insects are crucial for the functioning and prosperity of all terrestrial ecosystems. Yet scientists are observing that their numbers and variety are declining worldwide. This phenomenon is generally known as Insect apocalypse.

The The reasons for this decline are manifolddiverse and removed from fully understood. Research like this helps to shut this gap. Plant toxin-mediated indirect effects of invasive species seem like one other cut within the Death by a thousand cuts from insects everywhere in the world.

Finally, our story is a story of science in motion. Scientists cannot fully anticipate how natural events can disrupt the best-laid research plans, especially in field projects. Floods, droughts, tornadoes, lightning strikes, insect plagues—our research groups have experienced all of them.

But sometimes researchers meet these challenges with creative ingenuity and scientific adaptability, and this will result in surprising breakthroughs in our understanding of this extraordinary world.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply