Countless parents across the country have recently dropped their children off in school for the primary time. This transition can bring a whirlwind of emotions: the heartache of claiming goodbye, the sadness of a permanently modified family dynamic, the uncertainty of what lies ahead—but in addition the pride of seeing your child move toward independence. Some may describe the goodbye as bittersweet or say they feel mixed emotions.

In this scenario, what would you do if I asked you to rate your feelings on a scale of 1 to 9, with 1 being essentially the most negative and 9 being essentially the most positive? Given the circumstances, this query seems silly – how do you rate this mix of fine and bad? However, this scale is usually utilized by psychologists to look at feelings in scientific studies, treating emotions as either positive or negative, but never each.

I’m a neuroscientist that examines how mixed emotions are represented within the brain. Do people ever really feel positive and negative emotions at the identical time? Or will we just switch backwards and forwards quickly?

What emotions do to you

Scientists sometimes define emotions as Brain and body states that motivate you towards or away from things. People typically experience them as either positive or negative.

If you're walking within the woods and see a bear, your heart rate and respiratory speed up, supplying you with the urge to flee – and doubtless helping you decide that may preserve your life. Many scientists would call this response the emotion “fear.”

Likewise, warm feelings around people you like create a desire to remain near them and nurture those relationships, helping to strengthen your social network and support system.

This approach to approaching and avoiding emotions helps explain why emotions evolved and what influence they’ve on decision making. Scientists have used it as a tenet within the try to search out out biology behind emotions.

But mixed emotions don't fit this framework. If opposing biological systems inhibit one another, and emotions are biological in nature, you possibly can't experience opposites at the identical moment. This conclusion would mean that it's unimaginable to have two opposing emotions at the identical time; you might have to alternate backwards and forwards as a substitute. Since scientists first theorized in regards to the biological basis of emotions, they’ve conceptualized mixed emotions in this fashion.

fstop123/E+ via Getty Images

Deciphering the biology of mixed emotions

The current methods for measuring emotions still treat positive and negative as opposite sides of a spectrumHowever, the researchers found that study participants often reported mixed feelings.

For example, people in several cultures experience certain feelings, corresponding to nostalgia And Aweas positive and negative at the identical time.

A research group found that the topics’ physiological responses – corresponding to heart rate and skin conductance – exhibit unique patterns in experiences which might be each disgusting and funnyin comparison with each category individually. This implies that disgusted and amused reactions actually occur concurrently to create something latest.

In a seemingly contradictory result, a study using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) Brain reactions to disgusting humor found no pattern of brain activity that was distinct from easy disgust. The brain states of people that reported each disgust and amusement appeared to reflect only disgust—not a novel pattern for a brand new mixed emotion.

But fMRI studies generally depend on averaging brain activity across different people and over a time period. The crux of the query – experiencing truly mixed emotions, or oscillating between positive and negative states – concerns what the brain does over time. It's possible that by taking a look at average brain activity over a time period, scientists can get a pattern that appears very just like an emotion – on this case, disgust – but they're missing vital details about how the activity changes or stays the identical from second to second.

Mixed feelings within the brain

To explore this possibility, I conducted a study to search out out whether mixed feelings are related to a unique brain state that remained stable over time.

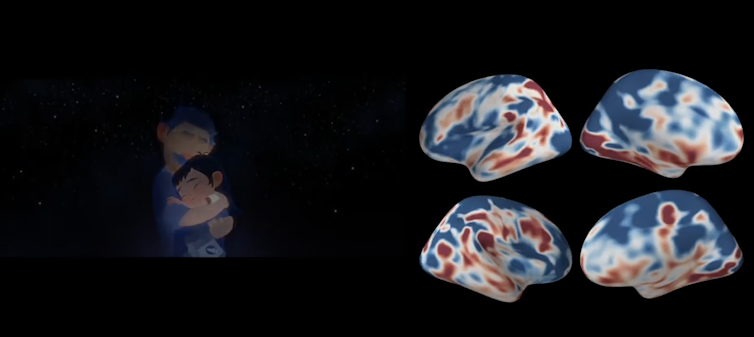

While lying within the MRI machine, participants watched a bittersweet animated short film a few young girl's lifelong quest to develop into an astronaut – with the support of her father. Spoiler alert: Her father dies. After the scan, the identical participants watched the video again and identified the precise moments once they felt positive, negative and mixed emotions.

Taiko Studios and University of Southern California Dornsife Office of Communications

My colleagues and I discovered that mixed emotions didn’t show unique, consistent patterns in deeper brain regions corresponding to the amygdala, which plays a crucial role in quick reactions to emotionally vital topics. Strikingly, the insular cortex, a component of the brain that connects deeper brain regions to the cortex, showed consistent and unique patterns for each positive and negative emotions, but not for mixed ones. We interpreted this result to mean that regions corresponding to the amygdala and insular cortex processed positive and negative emotions as mutually exclusive.

But we now have seen unique, consistent patterns in cortical regions corresponding to the anterior cingulate area, which plays a crucial role in Conflict and uncertainty processingand the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which is very important for Self-regulation and complicated pondering.

These brain regions within the cortex that perform more complex functions appear to represent rather more complex states that allow someone to actually experience mixed emotions. Brain regions corresponding to the anterior cingulate and ventromedial prefrontal cortex integrate many sources of data – essential to forming mixed emotions.

Our results also fit with what scientists find out about brain and emotion development. Interestingly, children don’t begin mixed feelings can only be understood or described in later childhood. This timeline is consistent with what researchers find out about how Development of those brain regions leads to more advanced emotion regulation and higher understanding.

What happens next?

This study has shed latest light on how complex emotions arise within the brain, but there’s rather more to explore.

One of the explanations mixed emotions are so interesting is because they’ll play a task in major life events. Sometimes mixed emotions enable you address big changes and switch into precious memories. For example, you may experience each positive and negative emotions when your folks throw you a giant farewell party before you progress to a different city on your dream job.

Sometimes mixed feelings are a continuing source of heartache. Even in case you know it’s best to break up along with your partner, that doesn't mean that every one the positive feelings you might have for them will robotically disappear or that a breakup can't be painful.

What causes this difference in end result? Could these differences have something to do with how the brain represents these mixed emotional states over time? A greater understanding of mixed emotions could help people be certain that these sorts of strong feelings develop into priceless memories that help them grow, slightly than an agonizing goodbye that they can’t recover from.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply