Hurricane Helene destroyed greater than 4 million homes and businesses at the hours of darkness through Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas after visiting Florida's Big Bend region strong category 4 storm Late on September 26, 2024. As rains moved inland in Helene, officials warned that broken utility lines needed to be repaired and power restored would take several days in some areas.

Electricity is significant for nearly everyone – wealthy and poor, young and old. But when severe storms strike, socioeconomically disadvantaged communities often wait the longest to get well.

This will not be only a perception.

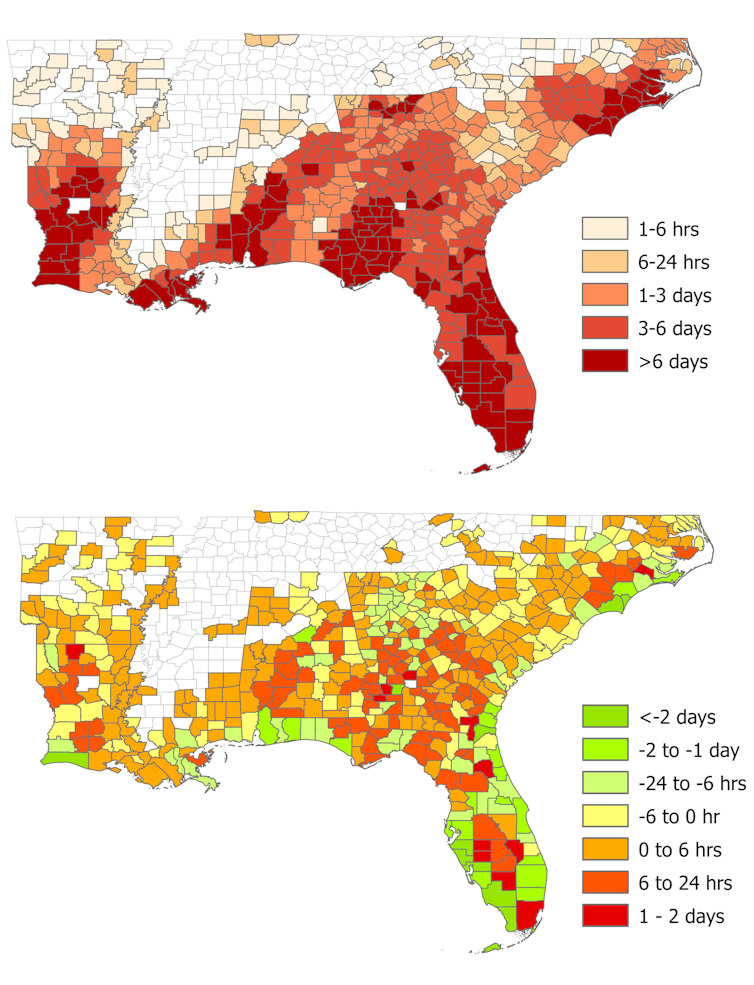

We analyzed Data from over 15 million consumers in 588 U.S. counties that lost power when hurricanes made landfall between January 2017 and October 2020. The results show that poorer communities actually waited longer for the lights to come back back on.

A ten percent decline in socioeconomic status within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Social Vulnerability Index was related to a mean 6.1% longer outage. This equates to a mean of a further 170 minutes waiting time, sometimes even longer, for power to be restored.

Ganz et al, 2023, PNAS Nexus

Impact on politics and utilities

A possible reason for this disparity lies in the knowledge provided by utility corporations. Standard storm recovery guidelines. When restoring power after an influence outage, these policies often prioritize critical infrastructure first after which large business and industrial customers. Next, they fight to revive as many households as possible as quickly as possible.

Although this approach could appear procedurally fair, these restoration routines appear to have the unintended effect of often making vulnerable communities wait longer for power to be restored. One Reason could also be that these communities are farther from critical infrastructure or are situated primarily in older neighborhoods where power infrastructure requires more extensive repairs.

Montinique Monroe/Getty Images

The result’s that there are households that do that already at greater risk Those affected by severe weather – whether because they’re in flood-prone areas or in vulnerable buildings – and people least prone to have insurance or other resources to assist them get well are also prone to face the longest storm-related power outages. Prolonged outages may end up in refrigerated food spoiling, lack of running water, and delays in repairing damage, including delays in running fans to dry out water damage and forestall mold.

Our study covered 108 utility regions, including investor-owned utilities, cooperatives, and public utilities. The disparate impacts on poorer communities weren’t as a consequence of any particular storm, region or utility. We also found no association with race, ethnicity, or residential type. Only the common socioeconomic level stood out.

How to make energy recovery less biased

There are ways to enhance power restoration times for everybody that transcend the crucial work to enhance power distribution stability.

Policymakers and utilities can begin by rethinking power restoration practices and power infrastructure maintenance, reminiscent of: B. replacing aging power poles and felling trees, while also keeping disadvantaged communities in mind.

Electric utilities have already done it Detailed power consumption data And Network performance of their supply regions. They can begin experimenting with alternative recovery routines that bear in mind their customers' vulnerability in a way that doesn’t significantly impact average recovery times.

Montinique Monroe/Getty Images

For socioeconomic endangered regions In areas where prolonged outages are expected as a consequence of their location and potentially aging energy infrastructure, utilities and policymakers can proactively make sure that households are well prepared for evacuation or have access to backup power sources.

The US Department of Energy announced in October 2023 that it might spend money on Develop dozens of resilience hubs and microgrids to assist provide local energy to critical buildings inside communities when the larger grid fails. Louisiana is planning several of those solar and large-scale battery hubs in or near disadvantaged communities.

Policymakers and utilities can even spend money on broader energy infrastructure and renewable energy in these vulnerable communities. The US Department of Energy Justice40 program notes that 40% of the profits from certain federal energy, transportation and housing investments profit disadvantaged communities. This may help residents who need public assistance probably the most.

As global temperatures rise, severe weather events have gotten more frequent. This increases the necessity for higher planning and approaches that don’t leave low-income residents at the hours of darkness.

Chenghao Duan, a Ph.D. student at Georgia Tech, also contributed to this text. This article, originally published on February 7, 2024, has been updated in light of the increasing variety of power outages attributable to Hurricane Helene.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply