After Kamala Harris chosen Minnesota Governor Tim Walz as her running mate, much of the media coverage focused on Walz's Midwestern roots, with some pundits using the phrase: “Minnesota beautiful” to explain his appeal.

In popular imagination, Minnesota describes a culture of neighborliness and friendliness that is mostly seen as characteristic of the state. In policy terms, this might mean greater investment in education, higher public health, access to inexpensive housing and stronger staff' rights – an expansion of Walz's achievements as governor of Minnesota. Many Americans probably want these values to prevail in the remainder of the nation.

I feel Minnesota's kindness, whether in politics or in kindness to neighbors, is a worthy ideal. But as someone who has studied the experiences of Vietnamese refugees in Minnesota, I actually have written about how the image of Minnesota has a more complex history – especially with regards to non-white people.

Rural origins

In her book “Creating Minnesota: A Story from the Inside Out“, historian Annette Atkins suggests that the phrase “Minnesota beautiful” may have its roots in the states Scandinavian Immigrants And the influence of the Lutheran Church.

According to Atkins, Minnesota nice means “a polite friendliness, an aversion to confrontation, a tendency to understatement… and emotional reserve.” These characteristics could be present in Scandinavian literature, film and art, in addition to in Lutheran values of the Nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

At the turn of the twentieth century 72% of Norwegian immigrants to Minnesota and 62% of Swedish immigrants to the state who lived in rural areas. And a core element of Minnesota Nice is the concept The residents are warmly welcoming to strangers from other countries.

The arrival of Southeast Asian refugees

After the top of the Vietnam War in April 1975, greater than 120,000 Vietnamese refugees got here to the United States. Another wave followed in 1978. Your arrival was not universally welcomed by the American public.

To address these concerns, government officials have taken motion a policy of dispersal to distribute the Southeast Asian refugees to make sure that they will not be concentrated in a selected region, town or city. They implemented these policies to scale back the social and economic impact on local communities – and likewise to force Southeast Asian refugees to integrate into American culture.

While many newcomers in Minnesota were helped, lots of them also experienced isolation and rejection.

From 1979 to 1999, about 15,000 Vietnamese refugees arrived in Minnesota. My research shows that media outlets often published articles highlighting the goodwill and generosity of locals, whether or not they helped these refugees learn English, gain vocational training, find work, or secure housing secure.

The Minneapolis Tribune reported in 1975 that the state was in a position to avoid major public backlash against refugees because they “not a significant job hazard“since they were spread everywhere in the state.

Even though the locals seemed to be largely supportive of the refugees, the distribution policy was not ideal for a lot of refugees. Many of them ended up in distant areas of Minnesota, removed from a well-recognized ethnic community that might provide much-needed psychological and emotional support. Those in distant areas Access was often lacking to social services and English language programs.

There is a more complicated view of Minnesota for refugees, which I feel depends upon not being too visible and never posing an excessive amount of of a threat to the present order. Many refugees were actually grateful for the state and native support they received. But gratitude also became a “unspoken state” for admission, because the Iranian refugee Dina Nayeri reports in her book “The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You.”

In Minnesota, locals seem largely incomprehensible to the complicated struggles of refugees attempting to settle in a wierd, recent land. Instead of complaining, they need to rejoice within the “little blessings” they’ve received. as one St. Cloud resident wrote to the Minneapolis Tribune in 1975.

Bruce Bisping/Star Tribune via Getty Images

Minnesota too beautiful

If an area experienced a sudden influx of refugees, some residents is perhaps even less welcoming.

This is what happened to the state’s Hmong refugees.

The Hmong, an ethnic group originally from China, arrived in Southeast Asia within the mid-Nineteenth century. During the Vietnam War, the US government recruited the Hmong to fight within the Vietnam War Secret war in Laoswhere the US had secretly provided aid and military support to anti-communist forces. After the war, some Hmong fled for fear of persecution. Many of them ended up in Minnesota. In 1980 there have been approx 2,000 Hmong People in Minnesota. By the top of 1981 their number had increased to eight,000, causing some concern.

“Some cynics say our problem is that we are too nice and have provided too many services,” a neighborhood resettlement official was quoted as saying in a 1980 State Department report. In the identical report, an official from a neighborhood charity suggested that Minnesota would soon be often called “Hmong-nesota.”

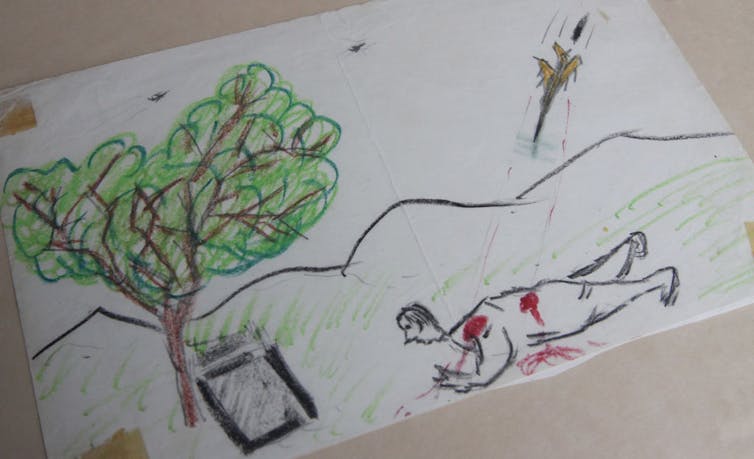

1985 the Minnesota Star Tribune published a special report“Hmong in Minnesota: Lost in the Promised Land,” which examined what number of Hmong refugees within the Twin Cities had grow to be “targets of racist epithets, harassment and violence.” The article states that the Hmong realized that the majority Americans had never heard of them or their role in the key war in Laos. Instead, they often felt “annoyed, misunderstood and bullied by their neighbors.”

For me, the fear of “Hmong-nesota” was paying homage to the story of “yellow peril” – the imagined threat of Asian invasion and cultural disruption that first emerged within the Nineteenth century and shaped many U.S. immigration policies.

Benevolence and violence

My own research examines how feel-good tropes common within the US, resembling Minnesota Nice, typically hide a more complicated story.

The U.S. government has often used the language of goodwill as a canopy for violence – a phenomenon that I “Bene/violence.”

For example, the US occupation of the Philippines, which began in 1899, was glossed over with the rhetoric of benevolence. William McKinley, then US President, insisted “The strong arm of authority” would “promote the blessings of good and stable government to the people of the Philippines under the free flag of the United States.” The story of the conquest became the history of the “upliftment” of those deemed less civilized and incapable of self-government.

Forrest Anderson/Getty Images

The same form of talk was also used to justify US military intervention in Vietnam. President Lyndon B. Johnson State of the Union address On January 4, 1965, he implored Americans to make sure the “peace of Asia” and “the progress of mankind.” The government promoted the war in Vietnam as a just war, including by claiming that the Americans would give the Vietnamese “justice.”Gift of freedom“, as Asian American scholar Mimi Nguyen has written.

Of course, this version ignores the events the carpet bombing Up to 1 million civilians died. This overlooks the proven fact that 30% of Laos continues to be covered in dust 80 million unexploded bombs and other ordnance. And it forgets to say how extensive use of the toxic herbicide Agent Orange continues to depart scars the Vietnamese landscape And the people of the country.

The Minnesota Paradox

In the top, Minnesota signals that the state is special, just as “spreading democracy” and “protecting freedom” signal American exceptionalism on the international stage.

But the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis highlighted what economist Samuel L. Myers called “The Minnesota Paradox“ — a story of inequality that’s entirely unrelated to the way in which kindness operates within the cultural imagination of the state’s residents.

“African-Americans are worse off in Minnesota than in virtually any other state in the country.” Myers writes.

The sociologist Amy August also writes in an essay from 2021 highlighted the state's ongoing racial disparities in housing, health care, income and education to argue that irrespective of what progressive guarantees the state makes, Minnesota will not be separate from America but fairly an element of America.

Ultimately, I feel the Minnesota Nice concept can create the illusion of a utopian society largely freed from the evils of racism and inequality. It reinforces American friendliness as a core aspect of national identity while, in my view, glossing over parts of the country's history — while hindering its ability to handle the very real problems plaguing the nation today.

I don't reject what Minnesota Nice claims to supply. But it will not be a straightforward and easy cultural value embraced by – and equally applied to – all.

![]()

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply