A tiny, living world thrives on the rocky bottom of most rivers. When sunlight falls through the water, Mayfly larvaeNo larger than a fingernail, they cling to algae-covered pebbles. Their brush-like mouthparts scratch the greenish coating, leaving faint marks as they feed. Six spindly legs anchor them against the present, while feathery gills gently wave backwards and forwards, drawing oxygen from the flowing water.

This shouldn’t be an unusual sight in well-maintained streams and rivers that flow through populated areas. But when wildfires rage, the toxins left behind can destroy this ecosystem.

When you’re thinking that of wildfires in cities, you would possibly picture charred trees and houses. But beneath the surface of nearby rivers, fires can even spark a silent unrest—one which affects populations of life forms which might be vital indicators of water health.

Camryn Miller

Forest fires are a natural component of many ecosystemsThey rejuvenate landscapes by removing dead shrubs and Release of nutrients from vegetation and soils.

However, when fires move from nature into residential areas, they encounter entirely different fuels. Urban fires devour a combination of synthetic and natural materials, including houses, vehicles, electronics and household chemicals. This creates a unique set of problems This can have far-reaching consequences for the waterways and the creatures that live there.

AP Photo/Noah Berger

As an environmental engineerI study how human activities on land affect the chemistry and ecology of surface water systems, including a vital group of river dwellers: benthic macroinvertebratesThese tiny creatures, which include mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies, usually are not only food sources for fish and other stream creatures, but additionally function natural guardians of water quality.

The Camp Fire 2018 was a wake-up call

In November 2018 the campfire devastated the town of Paradise, California, destroying over 18,000 homes and other buildings. After this tragic event, my colleagues and I examined the consequences of large-scale fires in cities on the chemistry of nearby watersheds.

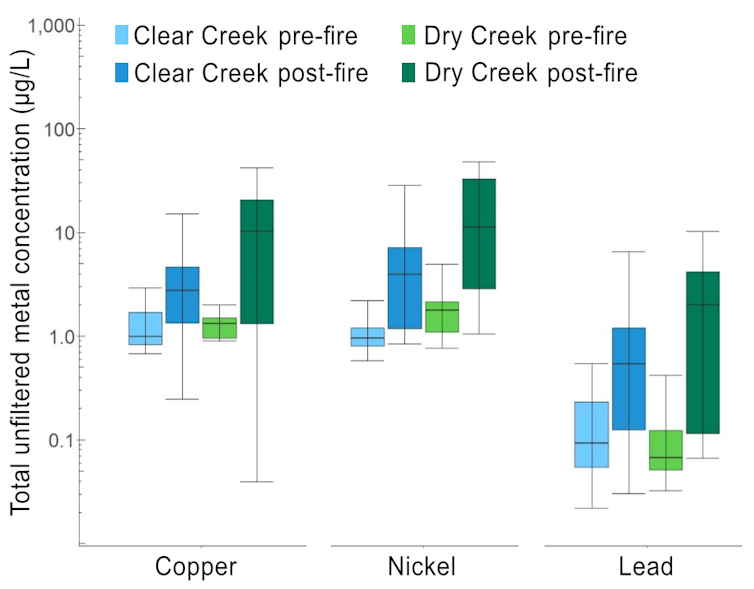

The results were alarming: Metal concentrations within the affected watersheds increased dramatically – as much as 2 hundred times in comparison with pre-fire levels. The concentrations of those metals exceeded EPA Acute Criteria for Aquatic Habitatsadvisable values that indicate when a metal has reached the brink of being “toxic” to aquatic organisms.

Lauren Magliozzi

These elevated metal levels can pose a risk to each ecosystems and human health.

For humans, contaminated watersheds can endanger drinking water sources by requiring extensive water treatment and even making some water supplies temporarily unusable.

Wildlife, especially sensitive aquatic animals comparable to fish and amphibians, are directly threatened by these pollutants. The toxic metals can disrupt their reproductive cycles, affect growth And Destabilize ecosystemsTiny macroinvertebrates on the ocean floor provide early warning of danger.

Silent witnesses: benthic macroinvertebrates

In the larval stage, benthic macroinvertebrates survive the benthos or bottom of the stream, where they’re continuously exposed to the water and are subsequently sensitive to changes within the chemical composition of the stream.

Fly fishermen might recognize these creatures as inspiration for the flies they tie. They are food for other aquatic life, but their presence, diversity and abundance also provide insight into short-term pollution events and long-term environmental changes that will not be detected by chemical testing alone.

Thom Quine via Wikimedia, From

Many species have short life cycles, allowing scientists to look at changes quickly. Different species even have different tolerances to pollution, providing a nuanced picture of water quality.

Marshall fire dramatically modified water quality

Just as we accomplished our evaluation of the Camp Fire samples on December 30, 2021, Marshall Fire devastated communities in my home state of Colorado and destroyed over 1,000 homes in Boulder County. Coal Creek Watershed.

Two years after the hearth, I worked with a team from the University of Colorado Boulder to watch water chemistry, benthic macroinvertebrate populations, and algae in Coal Creek. We found that runoff from fire debris dramatically modified each the water quality and the ecological balance on the sites affected by the hearth.

Lauren Magliozzi, CC BY-ND

Our results showed persistently elevated levels of toxic metals and declines in sensitive aquatic species, suggesting potential long-term risks to human activities comparable to fishing and irrigation. They also showed that recovery would likely take a few years.

Forest fires in cities cause toxic cocktails for rivers

Similar to the Camp Fire, we observed within the urban fire-affected areas of Boulder County increased concentrations of nutrients and metalsincluding copper, nickel, lead and zinc. By measuring the rainwater, we were capable of prove that these pollutants were transported by concrete drainage systems that quickly diverted the water into the stream. We found 84 cases where the metal concentrations were exceeded EPA Aquatic Life Limits in the primary yr.

We also found significant changes in the kind and variety of benthic macroinvertebrates present. One of probably the most striking findings was the impact on algae-feeding Mayflies which might be particularly sensitive to changes the water quality.

In the burned urban section of the creek, we observed an interesting phenomenon: abundant algae growth but fewer algae-eating mayflies. This suggests that fireside runoff has a dual effect on the creek ecosystem: nutrients from the burned vegetation likely stimulate algae growth, while toxic metals from the urban fire debris appear to negatively affect sensitive organisms comparable to mayflies.

Although the algae are quite a few, they will accumulate toxic metals from the water. If other organisms eat the algae, they might potentially absorb these metals as well. This process, often called bioaccumulation, can result in increasing concentrations of toxic substances moving up the food chain.

What does the evidence mean?

It's vital to notice that the total impact of urban wildfires on river life continues to be being studied. We can't yet say definitively whether numbers are low because those organisms are dying, or if there are more subtle effects, comparable to reduced reproduction. However, the decline in mayfly populations is a worrying indicator of the stress on the ecosystem.

AP Photo/Brennan Linsley

For humans, the impacts are complex. Although Coal Creek shouldn’t be a source of drinking water, it’s used for irrigation and recreation. Metal-contaminated water could accumulate in river sediments and further harm sensitive organisms in the long run.

The overall health of the stream also affects its ability to filter water and support biodiversity.

Protection of water bodies and their ecosystems

The story these streams and their tiny inhabitants tell is evident: urban wildfires pose a serious threat to water quality and aquatic life. To protect streams, communities must reduce fire risk and subsequent runoff. Improving urban planningStormwater management and watershed monitoring will help protect water resources.

The health of rivers affects the health of communities, and everybody can profit from heeding the mayflies' warning.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply