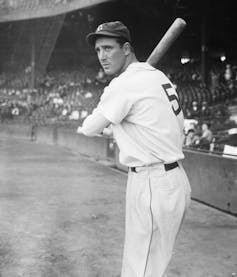

Hank Greenberg could be the best baseball player you've never heard of.

Greenberg was the one Detroit Tigers first baseman within the Nineteen Thirties and Forties. His profession was relatively short – 13 years – and was interrupted by two tours in World War II.

But outside of the war years there have been glorious seasons.

Greenberg led the American League in home runs 4 times, appeared in five All-Star Games, won the American League's Most Valuable Player Award twice, and nearly broke the sport's then-highest scoring record in 1938: Babe Ruth's 60 home runs in a season. In 1956, Greenberg was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Greenberg was also Jewish and is usually called that America's first Jewish sports superstar. As Greenberg wrote in his autobiographythat was no easy honor. Greenberg played during a time of rising anti-Semitism, and the cruel taunts he faced from players and fans continued throughout his profession. Disgusting remarks and bigoted insults – “Kike,” “Sheenie” and “Jew bastard” were typical – left a mark on him and the game he loved.

Along the best way, Greenberg also faced a crisis of conscience: He struggled with whether to play on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the high Jewish holidays. He resolved the conflict with a Solomonic decision greater than 30 years before baseball legend Sandy Koufax thought of it the identical dilemma in the course of the 1965 World Series.

Today, nearly 80 years after Greenberg retired from baseball, Anti-Semitism is increasing again each within the US and worldwide. As a historian of American sportsI suggest that there are lessons to be learned from how Greenberg handled the hate.

Bettmann via Getty Images

Horns just like the devil

Greenberg signed with the Tigers in 1930 and played within the minor leagues for the following three years. For lots of his teammates, he was the primary Jewish person they’d ever met. One person seriously told Greenberg that he believed Jewish people had horns, just like the devil.

After breaking into the main leagues, Greenberg was widely accepted by his teammates. The same can’t be said for opposing players and fans who followed him throughout his profession. The fans who insulted Greenberg were clearly within the minority, but they were loud, incessant, and met with virtually no resistance from other fans or the media.

Greenberg's response to the abuse: Ignore it. But he responded at the very least once, during a game against the Chicago White Sox. One Chicago player tried to harm Greenberg – his autobiography doesn’t record how – and one other called him a “yellow Jew son of a bitch.” After the sport, Greenberg visited the opposing team's locker room and desired to know who the namesake was. At 6 feet tall and weighing over 200 kilos, Greenberg looked intimidating. The room became quiet. The White Sox players never angered him again.

Other pressures were on Greenberg. Detroit was a hotbed of anti-Semitism within the Nineteen Thirties. The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper owned by the Industrialist Henry Forddescribed Jews as “the most important problem on this planet“, an echo of Ford's anti-Semitic beliefs. The city was also home Father Charles Coughlina Catholic priest who denigrated Jews and spread anti-Semitic rhetoric during his radio show – which reached its peak heard by perhaps 40 million people. Abroad, Adolf Hitler was the leader of Germany, and his persecution of the Jews became much more evident thereafter Kristallnacht, November 1938when the Nazi regime raged anti-Semitic.

“I felt,” Greenberg later wrote, “that if I hit a home run as a Jew, I beat one against Hitler.”

Bettmann via Getty Images

Playing on Jewish holidays

In 1934, when he was 23, Greenberg decided to not play on the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, a vacation on which observant Jews were purported to pray and never work. But the Tigers were in a decent race for the American League pennant. The team needed Greenberg, its star player.

An area newspaper reporter interviewed a Detroit rabbi and asked whether it was acceptable for Greenberg to play along. The Rabbi said it was high quality. Greenberg made a last-minute decision to play and hit two home runs. Detroit won the sport 2-1. The Detroit Free Press ran a headline in Yiddish with an English translation: “Happy New Year, Hank.”

Ten days later got here Yom Kippur, the holiest of all Jewish holidays. Also referred to as the Day of Atonement, observant Jews spend the day in prayer and self-reflection. Baseball wasn't on the agenda. This time Greenberg didn't play and as a substitute attended the service. When he entered the synagogue, the congregation applauded.

The Tigers lost 5-2 to the New York Yankees that day. But Detroit still won the pennant.

“I used to resent being singled out as a Jewish football player,” Greenberg said in his autobiography. “I'm not sure why or when that changed because I'm still not a particularly religious person. Lately, however, I want to be remembered as more than just a great ballplayer; but even more as a great Jewish ballplayer.”

Meeting with Robinson

1947 was Jackie Robinson's debut yr and Greenberg's last. Robinson, the primary baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers, had broken the colour line and was a baseball player first black player of recent times; He endured tremendous abuse, which Greenberg, now with the Pittsburgh Pirates, clearly understood. They played one another for the primary time at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh in May.

Bruce Bennett via Getty Images

In the fourth inning, Greenberg went to first with a walk, and in response to newspaper reports he had just a few words for Robinson: “I know it’s pretty hard,” he said. “You’re a good ballplayer, and you’ll do well.”

Greenberg also publicly supported Robinson, one in all the few opposing players to accomplish that.

Nearly half a century later, Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer considered whether the Supreme Court should convene on Yom Kippur. you too was inspired by Greenberg; Ginsburg noted that Greenberg “did not betray his conscience.” The Supreme Court didn’t meet on Yom Kippur this yr and has not met since.

Although tremendous progress has been made, racial and ethnic slurs live on in American sports. In 2024, some fans directed racially offensive comments two black players on the United States men's national soccer team. English football – referred to as soccer within the US – has Muslim players reported widespread discrimination and abuse. Things have modified, but not enough.

Although he was not an observant Jew, Greenberg understood that he needed to embrace his identity so as to endure the abuse. Today's athletes, who’ve recently suffered the hatred of bigots and trolls, should want to heed the teachings learned from this understated hero of the last century, a person whose quiet dignity spoke volumes.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply