The ancient Maya believed that every part within the universe, from the natural world to on a regular basis experiences, was a part of a single, powerful whole spiritual power. They weren’t polytheists who worshiped different gods, but Pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations this power.

The best evidence of that is the behavior of two of probably the most powerful beings within the Mayan world: the primary is a creator god whose name continues to be spoken by thousands and thousands of individuals every autumn – Huracán or “Hurricane”. The second is a god of lightning, K'awiil, from the early first millennium AD

As Scholar of the indigenous religions of the AmericasI recognize that although these beings are over 1,000 years apart, they’re related and have something to show us about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán, the “Heart of Heaven”

Huracán was once a god of the K'iche', one among the Mayan peoples who now live within the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one among the primary characters of the Popol Vuha spiritual text from the sixteenth century. Probably his name has its origins within the Caribbeanwhere other cultures used it to explain the destructive power of storms.

The K'iche' associated Huracán, which suggests “one leg” within the K'iche' language, with the weather. He was also their chief god of creation and accountable for all life on Earth, including humans.

For this reason it was sometimes known as U K'ux K'aj, or “Heart of Heaven.” In the K'iche' language, k'ux was not only the center but in addition the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Still, Huracan wasn't perfect. He made mistakes and sometimes destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who harmed people in order that they might not be equal to him. He is believed to have done it in a single such episode clouded her visionthereby stopping them from seeing the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was a being that existed as three different people: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied several types of lightningfrom huge flashes to small or sudden flashes of sunshine.

Although he was a god of lightning, there have been no strict boundaries between his powers and people of other gods. Any one among them could use lightning, create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

Another storm god

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and adapt their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. A thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was one other version of Huracán called K'awiil. In the primary millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras worshiped him because the god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

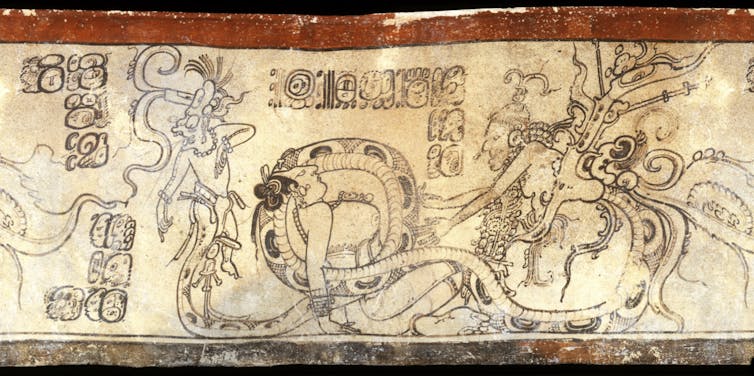

K5164 from the Justin Kerr Maya Archives, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees of Harvard University, Washington, DC, CC BY-SA

Images of K'awiil are found throughout Maya pottery and sculpture. In many depictions he is nearly human: he has two arms, two legs and a head. But his brow is the spark of life – and so there is often something with sparks protruding from it, resembling a flint ax or a burning torch. And one among its legs doesn't end in a foot. In their place stands a snake with an open mouth, from which one other creature often emerges.

In fact, rulers and even gods once performed ceremonies for K'awiil to summon him other supernatural beings. As personified lightningHe was believed to create portals to other worlds through which ancestors and gods could travel.

Representation of power

To the traditional Maya, lightning was raw power. It was fundamental to all creation and destruction. For this reason, the traditional Maya carved and painted many images of K'awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a type of energy – as a god with “many faces” or whilst a part of a triad much like Huracan.

It was found in all places in ancient Mayan art. But he was never the focus either. As a raw power, it was utilized by others to attain their goals.

Rain gods for instance, swung it like an axe, Generation of sparks in seeds for agriculture. Summoners summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Even rulers carried scepters in dances and processions modeled after him.

Furthermore, Maya artists all the time had K'awiil doing something or getting used to make something occur. They believed that power was something you do, not something you will have. Like lightning, the force was continually shifting, all the time moving.

An interdependent world

For this reason, the traditional Maya believed that reality was not static but was continually changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and Timethe forces of nature or the living and inanimate worlds.

AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, every part could turn into something else – and every part would potentially be a living being. Rulers could ritually transform themselves into gods. Sculptures could possibly be hacked to death. Even natural features resembling Mountains were considered alive.

These ideas, common in pantheistic societies, persist today some communities in America.

They were once mainstreamHowever, 1000 years later, on the time of Huracán, they were a part of the K'iche' religion. One of the teachings of the Popol Vuh, recounted within the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the Human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is just not that various things exist. Rather, it’s that they exist independently of one another. In this sense, Huracán has harmed himself by damaging his creations.

The annual hurricane season should remind us that humans will not be independent of nature, but relatively a component of it. And like Hurácan, after we harm nature, we harm ourselves.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply