Hundreds of commercial plants with toxic pollutants are in operation The path of Hurricane Milton en path to Florida, lower than two weeks later Hurricane Helene flooded communities across the Southeast.

Milton, which is predicted to make landfall as a serious hurricane late on October ninth, is Pressure on boat and spa factories along Florida's west-central coast, together with the rubber, plastic and fiberglass manufacturers that offer them. Many of those facilities eat tens of hundreds of registered pollutants every year, including toluene, Styrene and other chemicals known to cause hostile effects on the central nervous system through prolonged exposure.

Further inland, along the Interstate 4 and Interstate 75 corridors and their feeder roads, there are lots of more manufacturers that use and store hazardous chemicals on-site. And many are in the best way of the storm's fierce winds heavy rain.

Rice University Center for Coastal Futures and Adaptive Resilience, CC BY-ND

Helene heavy rain End of September 2024 flooded industrial sites across the southeast. A decommissioned nuclear power plant south of Cedar Key, Floridawas flooded by the storm surge from Helene.

In disasters like these, industrial damage can spread for days, and residents may not learn concerning the release of toxic chemicals into the water or air until days or even weeks later. in the event that they even discover.

Nevertheless, pollutant releases often occur.

After Hurricane Ian flooded Florida's west coast in 2022, runoff spilled containing thousands and thousands of gallons of sewage in addition to hazardous materials from damaged storage tanks and native fertilizer mining facilities visible from spaceand spills over the coastal wetlands into the Gulf of Mexico. A 12 months earlier, Hurricane Ida triggered More than 2,000 reported chemical accidents.

During Hurricane Harvey in 2017, floodwaters inundated chemical plants near Houston. Some caught fire when the cooling systems failedLarge amounts of pollutants are released into the air. emergency services and residents, Those who didn't know what risks they could be exposed blamed the chemicals to cause respiratory diseases.

Many varieties of Toxins can spread, settle and alter the long-term health and environmental safety of surrounding communities – often without residents being aware of it. Our team from Environment sociologists And Anthropologists has mapped hazardous industrial sites across the country and matched them with predicted hurricane impact maps to assist communities hold nearby facilities accountable.

Major Gulf Coast polluters are at grave risk.”

The risks posed by industrial facilities are most evident on the U.S. Gulf Coast, where there are numerous large petrochemical complexes Are bundled in peril. These refineries, factories and storage facilities are sometimes built along rivers or bays to permit easy accessibility for shipping.

But these rivers may also cause storm surges, which may raise the ocean several meters during hurricanes. Helene's storm surge was over 10 feet above the bottom in Big Bend, Florida 6 feet in Tampa Bay. With Milton, meteorologists warn of 1 10 to fifteen foot storm surge in Tampa Bay.

AP Photo/David J. Phillip

A recent study found evidence of this two to thrice more pollution fewer releases during hurricanes within the Gulf of Mexico than during normal weather from 2005 to 2020.

The impacts of those pollutant emissions disproportionately affect low-income communities and folks of color, further exacerbating the situation Environmental health risks.

Why residents may not know concerning the release of toxic substances

The statistics are disturbing, but they receive little attention. This is because hazardous releases remain largely invisible as a consequence of limited disclosure requirements and little public information. Even Emergency responders They often don't know exactly which dangerous chemicals they might be confronted with in emergency situations.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires major polluters to file paperwork just very general information about chemicals and risks on site of their Risk management plans. Partly large areas Fuel storage facilitiesFor example, those that transport liquefied natural gas will not be even obliged to accomplish that.

These risk management plans describe “worst case” scenarios and ought to be publicly available. But in point of fact we’re and others found them difficult accessible, heavily edited and housed in federal reading rooms with limited access. The reason for that is local officials and national scientific review panels The secrecy often serves to guard the facilities from terrorist attacks.

AP Photo/David J. Phillip

Adding to this opacity is the indisputable fact that many states, including those within the Gulf, are lifting restrictions on the discharge of pollutants when declaring emergencies. Meanwhile, real-time incident notifications are provided by the National Response Center – the federal government’s final repository for all chemical discharges into the environment – typically with a delay of every week or more,

We imagine this limited public information concerning the increasing chemical threats posed by our changing climate ought to be on the front page every hurricane season. Communities should pay attention to the risks related to housing vulnerable industrial infrastructure, especially as rising global temperatures increase the chance of utmost rainfall events strong hurricanes.

Nationwide risk mapping to boost awareness

To help communities understand their risks, our team at the brand new Center for Coastal futures and adaptive resilience examines how industrial communities in flood-prone areas across the country can higher adapt to such threats, each socially and technologically.

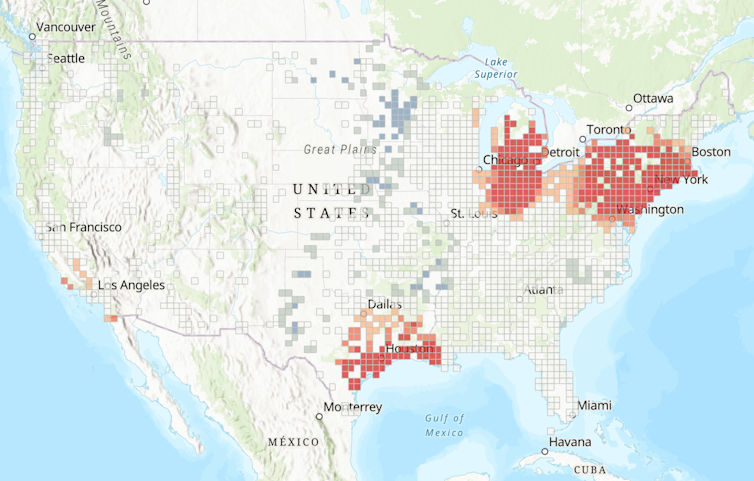

Our interactive map shows where increased future flood risks could flood the key polluters we discover using EPAs Inventory of toxic releases.

There are several hotspots within the United States with clusters of flood-prone polluters. The largest include the Ship Channel in Houston, the waterfront steel industry in Chicago and the ports in Los Angeles and New York/New Jersey.

Rice University Center for Coastal Futures and Adaptive Resilience, CC BY-ND

But as Helene revealed, there can be big concerns in less obvious places. Inland, particularly within the mountains, runoff can quickly turn normally calm rivers into rapidly rising torrents. The French Broad River in Asheville, North Carolina rose about 12 feet during Helene and in 12 hours set a brand new flood stage record.

When hurricanes and tropical storms head toward the U.S., our interactive maps show where the largest polluters are positioned within the storm's projected impact cone. The maps discover dangerous, flood-prone facilities right down to the address, anywhere within the country.

Knowledge is step one

Knowing where these sites are positioned is just step one. Often it’s as much as the communities themselves, lots of them already overexposed and historically underservedto boost concerns and call for strategies to mitigate the health, economic and environmental risks that will arise from industrial sites liable to flooding and other damage.

These discussions cannot wait until disaster strikes. When communities understand where these risks might lie, they will take motion now to construct a safer future.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply