Long before colonialism brought slavery to the Caribbean, native islanders saw hurricanes and storms as such Part of the conventional life cycle.

The Taino the Greater Antilles and the KalinagoThe Caribs of the Lesser Antilles developed systems that allowed them to live with storms and limit their exposure to wreck.

On the larger islands reminiscent of Jamaica and Cuba, the Taino used to practice plant selection with storms in mind, preferring to plant root crops reminiscent of cassava or yucca, which have high resistance to wreck from hurricanes and storm winds, as Stuart Schwartz describes in his 2016 book “Sea of Storms.”

The Kalinago avoided constructing theirs Settlements along the coast to limit storm surges and wind damage. The Calusa in southwest Florida used trees as windbreaks against storm winds.

In fact they were Kalinago and Taino who was the primary to show the Europeans – especially the British, Dutch, French and Spanish – about hurricanes and storms. Even those The word “hurricane” comes from Huracána Taino and Mayan word that denotes this God of the wind.

But then colonialism modified all the pieces.

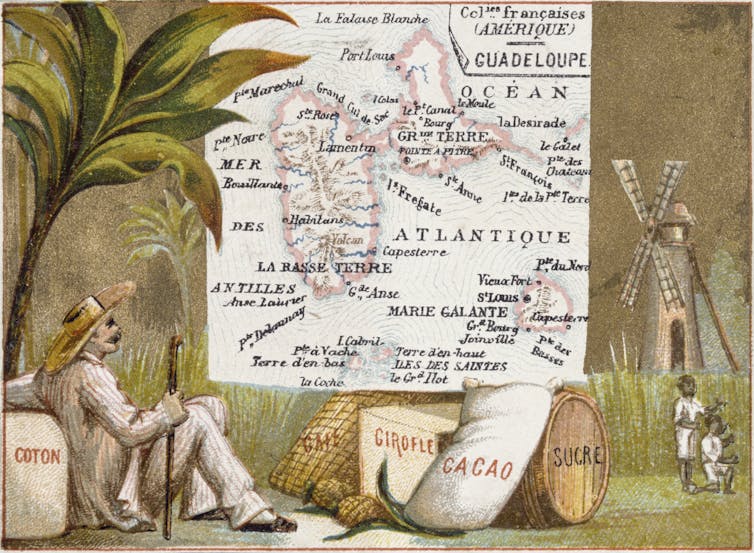

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

I Study natural disasters within the Caribbeanincluding how history shapes responses to disasters today.

The current disaster crisis that the small Caribbean islands are experiencing because of increasing hurricanes didn’t begin several a long time ago. Rather, it’s Vulnerability of the islands is a direct results of the exploitative systems imposed on the region by colonialism, its legacies of slave-based land policies and inappropriate construction and development practices Environmental injustices.

Put people in peril

The colonial powers modified the way in which people within the Caribbean interacted with one another with the land where they lived and the way they recovered from natural disasters.

Instead of growing crops that would sustain the local food supply, the Europeans who arrived within the sixteenth century focused on exploitative economic models and the export of money crops through the United States Plantation economy.

They forced the indigenous people to go away their land and built settlements along the coastwhich facilitated the importation of enslaved peoples and goods and the export of money crops reminiscent of sugar and tobacco to Europe – and in addition left communities vulnerable to storms. They also established settlements in low-lying areas, often near rivers and streams, which enabled the transport of agricultural products but became a flood risk during heavy rainfall.

Helene Valenzuela/AFP via Getty Images

Today, greater than 70% of the Caribbean's population lives on the coast, often lower than a mile from the shore. These coasts usually are not only highly exposed to hurricanes, but in addition to sea level rise brought on by climate change.

Legacies of slave-based land policy

Today, the legacy of colonial land policies has also made recovery from disasters rather more difficult.

When the colonial powers took power, a couple of landowners got control of a lot of the land, while the vast majority of the population was forced into marginal and small areas. The local population had no legal right to the land as people didn’t possess land deeds or deeds and were often forced to pay rent to the landowners.

After independence, most island governments tried it To acquire land from former plantations or estates and redistribute it to the working class. But these efforts, especially within the Sixties and Seventies, largely failed to rework land ownership, improve economic development or reduce vulnerability.

One colonial legacy that continues vulnerability to at the present time is what’s often called Crown land or state land. In the English-speaking Caribbean, all properties for which there was no land grant were taken under consideration Property of the British Crown. Crown land still exists on every English-speaking island today.

In Barbuda, for instance, all land is owned by the “Crown forever” on behalf of the Barbudans. This signifies that an individual born on the island of Barbuda cannot own their very own land.

Instead there may be land common propertywhich limits access to much-needed credit and development opportunities Reconstruction of the island after Hurricane Maria in 2017. Most Barbudans were unable to insure their homes because they’d no title deeds for his or her property.

This and other collective Land tenure systems created by colonialism burden Caribbean residents increased risk from a wide range of natural hazards and limits their ability to use for disaster recovery financial loans today.

The roots of poor construction

Vulnerability to disasters within the Caribbean also has its roots within the post-slavery era housing after which Failure to implement proper constructing regulations.

After liberation from slavery, freed people had no claim or access to land. In order to construct houses, they were forced to rent land from former slave owners, who could terminate their employment or drive them off the land at their whim.

This led to the event of a special variety of residential structure often called movable houses in countries like Barbados. These houses are tiny and were built in order that they may very well be easily disassembled and loaded onto carts should the residents be displaced by their former slaves. Still a lot of Bajans live in these houses todayalthough a few of these have been converted into restaurants or shops.

Shardalow via Wikimedia, CC BY

In Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, owned by the Dutch, Slave cabins were built along the coaston land that isn’t suitable for agriculture and is well damaged by storms. These former slave cabins at the moment are tourist attractions, but colonial settlement patterns along the coast have left many coastal communities abandoned Exposed to wreck from hurricanes And rising seas.

The vulnerability of such houses isn’t only because of the exposure to natural hazards, but in addition to the underlying social structures.

Leslie Ket via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

On many islands today, poorer residents cannot afford protective measures reminiscent of installing storm shutters or purchasing solar-powered generators.

She often live in peripheral areas and areas vulnerable to disastersreminiscent of steep slopes, where housing tends to be cheaper. Houses in these areas are also often poorly constructed and fabricated from inferior materials, reminiscent of galvanized sheets for roofs and partitions.

This situation is made worse by the informal and unregulated nature of housing construction within the region and the United States poor enforcement of constructing regulations.

Due to the legacy of colonialismMost housing or constructing standards or regulations within the Commonwealth Caribbean are relics from the United Kingdom and within the French Antilles from France. Construction standards across the region usually are not uniform and are generally subjective and uncontrolled. Financial restrictions and staffing shortages mean codes and standards are sometimes not enforced.

Progress is being made, but there continues to be lots to do

The Caribbean has made progress in development wind-related constructing regulations I actually have been attempting to increase resilience over the past few years. And while damage from torrential rain continues to be not adequately accounted for in most Caribbean constructing standards, scientific guidance is accessible through the Caribbean Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology in Barbados.

Individual islands, including Dominica And Saint Luciahave recent minimum construction standards for disaster recovery. The island of Grenada hopes so Guide for brand spanking new construction because it recovers from Hurricane Beryl. Trinidad and Tobago has developed one National Land Use Strategy but has had trouble using it.

Building standards can assist islands strengthen their resilience. However, much stays to be done to beat the legacy of colonial-era land policy and development that has left island cities vulnerable to increasing storm risks.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply