In the United States, the second Monday in October is increasingly often called Indigenous Peoples Day. In the try and rename Columbus Day, Christopher Columbus himself has change into a metaphor for the evils of early colonial empires, and rightly so.

The Italian explorer who set out across the Atlantic in quest of Asia was a notorious advocate of Enslavement of the indigenous Taínos the Caribbean. In the words of Historian Andres ResendezHe intended to “turn the Caribbean into another Guinea,” the region of West Africa that had change into a European center of the slave trade.

By 1506, nevertheless, Columbus was dead. Most of the genocidal violence that characterised the colonial era was committed by many, many others. In the long shadow of Columbus, we sometimes lose sight of the ideas, laws, and peculiar those who made colonial violence possible on a large scale.

As a historian of colonial Latin AmericaI often begin such discussions by pointing to a peculiar document written several years after Columbus' death that may have a greater impact on indigenous peoples than Columbus himself: the requirementor “requirement”.

Catch-22

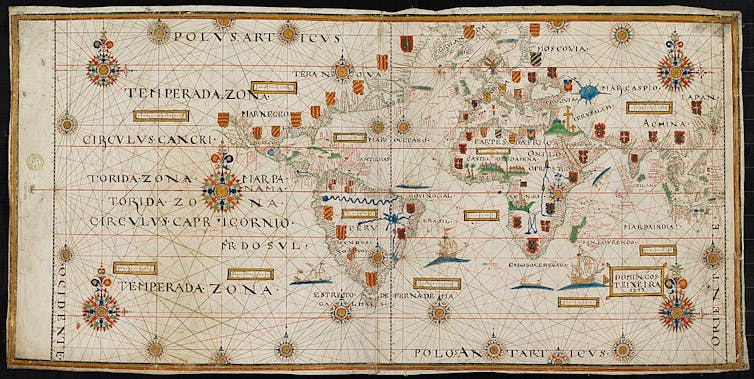

In 1494 the Treaty of Tordesillas infamously divided much of the world outside Europe into two halves: one for the Spanish crown, the opposite for the Portuguese. The Spanish laid claim to almost your entire American continent, despite the fact that they knew almost nothing about this vast area or the individuals who lived there.

National Library of France via Wikimedia Commons

To inform the indigenous peoples that they’d suddenly change into vassals of Spain, King Ferdinand and his councilors instructed the colonizers to read the Requerimiento aloud upon first contact with all indigenous groups.

The document presented to them a selection that was no selection in any respect. They could either change into Christians and undergo the authority of the Catholic Church and the King, or:

“With the help of God we will invade your lands with force and make war against you in every way possible… We will take you and your wives and your children and make them slaves… the death and damage that will result from this, are your fault.”

There was a catch. According to the document, indigenous peoples could either voluntarily surrender their sovereignty and change into vassals or wage war on themselves – and maybe still lose their sovereignty after much bloodshed. No matter what they selected, the Requerimiento provided the legal pretext for the forcible incorporation of sovereign indigenous peoples into Spanish rule.

At its core, the requerimiento was a legal ritual, an exercise of ownership – and it was unique to early Spanish imperialism.

“As absurd as it is stupid”

Despite its apparent authority, reading the Requerimiento was an absurd exercise. It first occurred in the course of the expedition in what’s now Santa Marta, Colombia under the leadership of Pedrarias Dávila in 1513. An eyewitness, the chronicler Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedostated the plain: “We don’t have anyone here who can help [the Indigenous people] understand it.”

But even with a translator, the document, with its grandiose references to the biblical creation of the world and papal authority, could be obscure for people unfamiliar with Spanish religion. To explain the complicated document would require nothing lower than an extended recitation of Catholic history.

Oviedo suggested this to provide such a lectureyou’ll first must catch and imprison an indigenous person. Even then, it will be inconceivable to confirm that the document was fully understood.

But for the best critic of the Requerimiento: Bartolome de las CasasThe translation was just one in every of many problems. Las Casas, a missionary from Spain, criticized the false demand itself: that a people ought to be expected to right away convert to a faith of whose existence they’ve only just learned, and

“swear allegiance to a king they have never heard of and never seen, and whose subjects and ambassadors turn out to be cruel, merciless and bloodthirsty tyrants.”… Such an idea is as absurd because it is silly and ought to be followed will likely be treated with the disrespect, contempt and contempt she so richly deserves.”

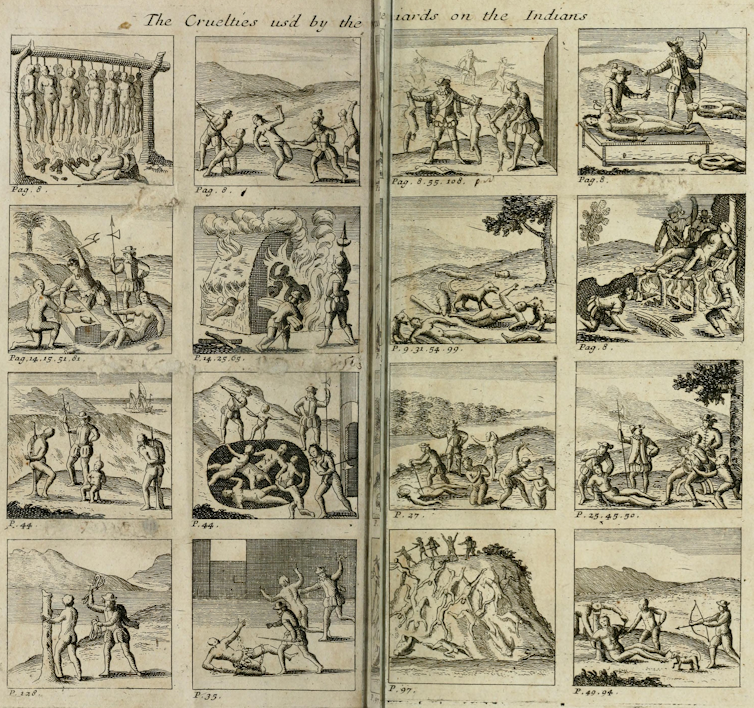

It was Las Casas, who documented abuses against indigenous peoples in several books and speeches one of the crucial outspoken informers of Spanish cruelty in America. While he believed that the Spanish had the best and even the duty to convert indigenous peoples to Catholicism, he didn’t consider that conversion should occur under threat of violence.

Wikimedia Commons

Wars and compelled settlements

The indigenous population responded to the requerimiento in a wide range of ways. When the Chontal Maya of Potonchan—a Mayan capital now a part of Mexico—heard the conquistador Hernando Cortés read the document thrice in a row, they responded with arrows. After Cortés conquered townThey agreed to change into Christian vassals of Spain on the condition that the Spaniards “leave their country.” When Cortés' men remained behind after three days, the Chontal Maya attacked again.

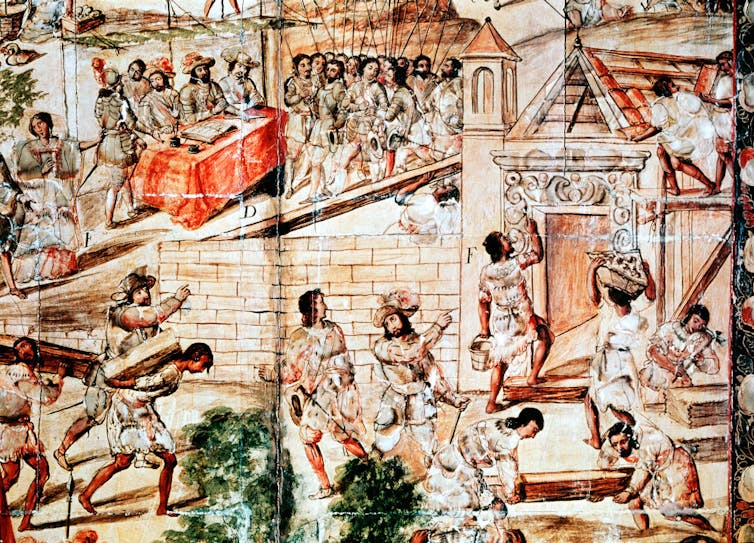

Further north: Spanish expeditionaries Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Melchior Díaz used the requerimiento to forcibly relocate various indigenous groups.

A bloodthirsty governor The provincial captain, Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán, was so violent that the Spanish themselves imprisoned him for abuse of power. He had driven indigenous residents from the Culiacán Valley in a series of brutal wars. However, in 1536, Cabeza de Vaca and Díaz forced several groups, including the Tahue, to repopulate the valley after convincing them to simply accept the terms of the Requerimiento.

The resettlement would allow for the gathering of tribute and conversion to Catholicism. It was simply easier to assign missionaries and tribute collectors to established Hispanic townships than to mobile communities spread over wide areas.

Cow head encouraged indigenous leaders to simply accept the proposal by claiming that their god Aguar was the identical as that of the Christians and that they need to due to this fact “serve him as we have commanded.” In such cases, converting to Catholicism was as absurd because the Requerimiento itself.

Violence and colonial legacy

But even when the indigenous population accepted the requerimiento, Las Casas wrote that “they are (still) treated harshly like ordinary slaves, forced to do hard labor and subjected to all kinds of abuses and excruciating torments, which ensure a slower and more painful death than summary execution.” In most cases, the requerimiento was merely a Precursors of violence.

Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

Dávila, the conqueror of what’s now northern Colombia, once read it out of earshot of a village, just before launching a surprise attack. Others read the Requerimiento “to trees and empty hutsbefore drawing their swords. The road to vassalage was paved with blood.

These are the truest signs of what became of the requerimiento on the bottom. In the pursuit of the spoils of war, soldiers and officials were content to make use of or surrender royal prerogatives by force at will.

And yet, despite the viciousness, many indigenous peoples survived by drawing their bows just like the Chontal Maya or negotiating a brand new relationship with Spain just like the Tahue of Culiacán. The tactics were very different and altered over time.

Many indigenous nations that practiced it survive today and long outlive the Spanish Empire—and the individuals who carried the Requerimiento on their crusade across the Americas.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply