In my research As I've focused on the early farmers of Europe, I've often wondered a couple of strange pattern over time: farmers lived in large, dense villages, then dispersed over centuries, later founding cities again, only to desert those as well. Why?

Archaeologists often explain what we call urban collapse Climate changeOverpopulation, social pressure or something similar Combination of those. Each of those was probably true at different times.

But scientists have added a brand new hypothesis to the combination: disease. The close coexistence with animals led to this zoonotic diseases that got here to contaminate people too. Outbreaks could have led to dense settlements being abandoned, at the least until later generations found a option to make their settlement structure more immune to disease. In a brand new study, my colleagues and I analyzed the fascinating floor plans of later settlements to see how they might have interacted with disease transmission.

Murat Özsoy 1958/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Earliest Cities: Dense with People and Animals

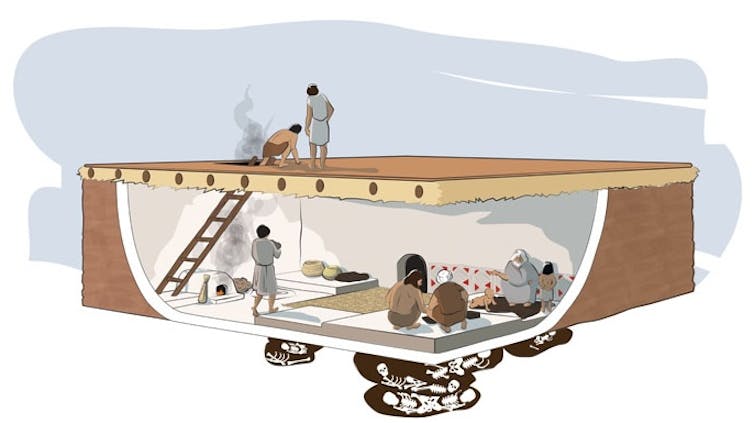

Çatalhöyükin what’s now Türkiye, is the oldest farming village on this planet with a history dating back over 9,000 years. Many hundreds of individuals lived in mud-brick houses that were packed so tightly together that residents could get in using a ladder through a trap door on the roof. They even buried chosen ancestors under the home floor. Although there was loads of space on the Anatolian plateau, people crowded together.

Illustration by Kathryn Killackey and the Çatalhöyük Research Project

For centuries, the people of Çatalhöyük herded sheep and cattle, grew barley and made cheese. Impressive paintings of bulls, dancing figures and others Volcanic eruption suggest their folk traditions. They kept their well-organized homes tidy, sweeping the floors and providing storage containers near the kitchen that sat under the trapdoor to permit oven smoke to flee. To maintain cleanliness, they even needed to re-plaster the inside partitions of their houses several times a 12 months.

These wealthy traditions ended around 6000 BC. BC, as Çatalhöyük was mysteriously abandoned. The population dispersed into smaller settlements in the encircling floodplain and beyond. Other large farming populations within the region had also dispersed, and nomadic pastoralism became more widespread. For the surviving populations, the mud-brick houses were now separate, in contrast to the metropolitan areas of Çatalhöyük.

Was disease a consider the abandonment of dense settlements in 6000 BC? BC?

In Çatalhöyük, archaeologists have found human bones mixed with cattle bones in graves and garbage heaps. There was probably a gathering of individuals and animals zoonotic diseases in Çatalhöyük. Ancient DNA identified Tuberculosis in cattle within the region as early as 8500 BC. BC and TB in human infant bones not long afterwards. DNA in ancient human stays dated Salmonella as early as 4500 BC BC. Assuming that the contagiousness and virulence of Neolithic diseases increased over time, dense settlements resembling Çatalhöyük can have achieved a Turning point where the consequences of disease outweighed the advantages of living close together.

2,000 years later a brand new layout

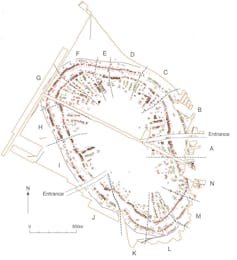

Around 4000 BC In the 4th century BC, large urban populations reappeared within the mega-settlements of antiquity Trypillia culturewest of the Black Sea. Thousands of individuals lived in mega settlements like Trypillia No longer And Maidanetske in today's Ukraine.

If disease was a consider the spread hundreds of years ago, how were these mega-settlements possible?

Duncan Hale and Nebelivka Project, CC BY-NC

This time the layout was different than in crowded Çatalhöyük: the a whole bunch of two-story wood houses were arranged usually in concentric ovals. They also grouped themselves into pie-shaped neighborhoods, each with its own large meeting house. The pottery unearthed from neighborhood meeting houses shows many various compositions, suggesting this These pots were brought there by different families come together to share food.

This layout suggests a theory. Whether the residents of Nebelivka knew it or not, this lower density, cluster arrangement could have helped prevent disease outbreaks from wiping out your entire settlement.

archaeologist Simon Carrignon and I got down to test this possibility by adapting computer models from a previous epidemiology project that modeled how social distancing behaviors play out have an effect on the spread of pandemics. To study how a Trypillian settlement would hinder the spread of disease, we teamed up with a cultural evolution scientist Mike O'Brien and with the archaeologists from Nebelivka: John Chapman, Bisserka Gaydarska And Brian Buchanan.

Simulating socially distanced neighborhoods

To simulate the spread of the disease in Nebelivka, we needed to make some assumptions. At first, we assumed that early diseases were spread through foods like milk or meat. Second, we assumed that folks visited other houses of their neighborhood more often than those outside.

Would this neighborhood clustering be enough to suppress disease outbreaks? To test the consequences of various possible interaction rates, we ran thousands and thousands of simulations, first on a network to represent grouped neighborhoods. We then ran the simulations again, this time on a virtual floor plan modeled after actual site plans, giving the homes in each neighborhood a better probability of coming into contact with each other.

Simulations by Simon Carrignon.

Based on our simulationsWe found that the clustering of homes in Nebelivka would have significantly reduced outbreaks of early foodborne illnesses if people had visited other parts of the town infrequently – a couple of fifth to a tenth as often as other houses in their very own neighborhood. This is sensible considering that every neighborhood had its own meeting house. Overall, the outcomes show how the Trypillian arrangement could help early farmers coexist in low-density urban populations at a time when zoonotic diseases were on the rise.

The residents of Nebilevka needn’t have consciously planned the design of their neighborhood to make sure the survival of their population. But it could be that they do, because human instinct is to avoid them Signs of a contagious disease. As in Çatalhöyük, residents kept their houses clean. And about two-thirds of it Houses in Nebelivka were deliberately burned down at different times. These intentional periodic burns can have been a pest control tactic.

Arheoinvest/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

New cities and innovations

Some of the early diseases eventually spread through routes apart from bad foods. Tuberculosis, for instance, was in some unspecified time in the future transmitted through the air. If the bacterium that causes the plague was adapted to fleasit could possibly be spread by rats that don't care about neighborhood boundaries.

Were latest disease vectors an excessive amount of for these ancient cities? The mega-settlements of Trypillia were founded in 3000 BC. Abandoned. As in Çatalhöyük hundreds of years ago, people dispersed into smaller settlements. Some geneticists speculate that Trypillia settlements were abandoned resulting from the origin of the plague within the region, about 5,000 years ago.

The first cities in Mesopotamia emerged around 3500 BC. BC, others soon emerged in Egypt Indus Valley And China. These cities, with tens of hundreds of residents, were filled with specialized craftsmen in numerous parts of the town.

This time people within the inner cities didn’t live side by side with cattle or sheep. Cities were the centers of regional trade. Food was imported into the town and stored in large grain silos just like the one within the Hittite capital Hattusa, which could contain enough grain Feed 20,000 people for a 12 months. Wastewater disposal was supported by public waterworks, resembling: Canals in Uruk or water fountain and a large public bath within the Indus city of Mohenjo Daro.

These early cities, together with those in China, Africa and the Americas, formed the foundations of civilization. Their form and performance have arguably been shaped by millennia of disease and human responses to it, all the best way back to the world's earliest farming villages.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply