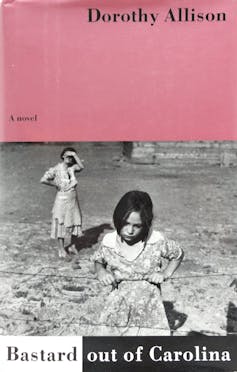

Dorothy Allison, who died on November 5, 2024published her first novel “Bastard from Carolina“, in 1992, when she was 42 years old.

She used her own life to create the semi-autobiographical work that it became a finalist for the National Book Award.

Allison grew up poor in Greenville, South Carolina, enduring all types of abuse before becoming the primary in her family to graduate from highschool and college. As a lesbianshe faced additional challenges and hurdles. Before she achieved literary fame together with her first novel, Allison ran a feminist bookstore and a women's center. She was broke when she finally sold Bastard Out of Carolina.

To me, Allison is a shining exception in an extended line of authors who’ve tried to jot down about poverty but fail to totally capture it.

In my book “Poor Things: How Those Who Have Money Represent Those Who Have No Money“I explain the genre of what I call “poornography” – stories written about poor people by individuals who haven’t themselves had the experience of being poor.

Most readers are probably aware of the usual themes of those works: violence, sexual abuse, addiction, filth, and degradation. Allison was clearly not in that camp.

She broke this mold by finding beauty in her impoverished surroundings and specializing in love, humor and family bonds.

Beauty in a hopeless place

Even if “Bastard out of Carolina” is ultimately about physical and sexual abuse – which after all it’s just isn’t limited to poor people – This represents only one element of a bigger emotional and physical landscape.

Allison's hometown of Greenville can also be the setting of the novel – and it’s a place that the novel's young narrator, Bone, describes as “the most beautiful place in the world.” She adds:

“Black walnut trees dropped their green-black, fluffy bulbs on Aunt Ruth’s matted lawn, past where their gnarled roots jutted from the ground like the elbows and knees of dirty, dark-tanned, scarred children. Weeping willows marched across the yard, following every wandering stream and ditch. Their long, whip-like fronds opened cracks that protected sweet-smelling beds of clover.”

However, extreme hunger only occurs in poverty and is something poor writers often remember with a vividness that will elude middle-class or wealthy writers.

“Hunger makes you restless,” writes Allison. “You dream of food, magical meals, famous and awe-inspiring, the one cut of meat, the precise taste of buttered corn, tomatoes so ripe they burst and sweeten the air, beans so crunchy they bite between the Teeth bursting, gravy like mother's.” Milk sings in your bloodstream.”

In “Bastard out of Carolina,” Allison doesn’t have fun hunger. But she manages to seek out humor in it and show how laughter might be used as a coping mechanism.

When Bone complains about hunger within the novel, her mother talks about her own childhood: Back then there was “real hunger, hunger for days, with no expectation that there would ever be cookies again.” And during this time she and her siblings made up improbable stories about strange dishes: “Your Aunt Ruth always talked about frogs’ tongues with dewberries. … But Raylene won the prize with her recipe for sugar-glazed turtle meat with poisonous greens and hot piss dressing.”

Humor just isn’t intended to obscure the severity of poverty. But Allison desires to indicate that each can exist: they’re all involved in a life lived.

Library of Congress

American madness

I can't help but compare Allison's work to that of an writer like JD Vance. His 2016 memoir states: “Hillbilly Elegy“Vance revels in his grandmother's anger and violence as an emblem of her feisty hillbilly spirit.

On the opposite hand, Bone remembers her mother saying flatly in “Bastard out of Carolina,” “It's nothing to be proud of when you shoot people who look at you the wrong way.”

So many other writers about poverty have characters who long for the fabric comforts promised by the American dream, be it Clyde Griffiths in Theodore Dreiser's “An American Tragedy” or George and Lennie in John Steinbeck’s “Of mice and men.”

Amazon

Allison's characters, however, learn to see through this false promise. In one scene, Bone and her cousin break in the local Woolworths.

Previously she had looked longingly at a bulging glass box stuffed with nuts. But when she smashes the display case, she realizes “that the display case was a deception.” There were not more than five centimeters of nuts pressed onto the glass front and supported with cardboard.” Her response: “Cheap sons of bitches.”

Reflecting his class consciousness, Bone eventually recognizes the false appeal of low cost goods. “I looked at all the things on display. Trash everywhere: shoes that broke in the rain, clothes that came apart at the seams, stale candy, makeup that cracked the skin.”

In contrast, she thinks in regards to the value of her aunt's homemade canned goods. “That was worth something. All that stuff seemed tacky and useless to us.”

“I'm jealous of you for what you have”

At one point Bone formulates the concept of poornography without using the term. She talks about “the mythology” that plagues poor people:

“People from families like mine – working poor people from the South with high illegitimacy rates and all too many relatives who have spent time in prison – we are the people who are seen as the class that doesn't take care of their children, that rapes and are mistreated.” and violence are the norm. That such assumptions are false, that the wealthy are as more likely to abuse their children because the poor, and that Southerners have a monopoly on neither violence nor illegitimacy are realities which can be difficult to make people understand.”

In “Bastard out of Carolina,” Bone resents the wealthy as an alternative of admiring them. In a conversation with one in every of her aunts, she says she “hates” them. Interestingly, her aunt provides the poor person's counterpoint to hatred.

“Maybe they're looking at you sitting up here eating blackberries… maybe they're jealous of you because of what you have and afraid of what you would do if they came into the yard.”

Allison shows readers how class animosity can go each ways and that for all of the contempt the wealthy and powerful have for poor people, there may also be a component of envy and fear at play.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply