Neither “gladiator” still its cinematic sequel is especially busy historical fact. For one thing, Emperor Marcus Aurelius had no intention of restoring the Republic. Gladiator fights were a hideous display of cruelty, nonetheless They didn't at all times end in death. And the Romans didn't create bone-white statues; They painted them with a spread of colours.

What interests me most, nonetheless, is how the 2 movies misrepresent the way in which Roman gladiators and their bodies were viewed by their republican-minded contemporaries.

In the movies, gladiators Maximus and Lucius' beefy biceps reflect “strength and honor” – to take up the motto again of suffrage – as each of those heroes fights to overthrow complacent emperors and restore the Roman Republic with its traditional political values of freedom and self-control.

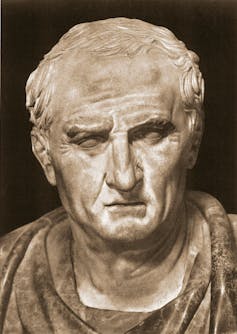

However, I describe in my book: “Vitruvian Man: Rome under construction“The Gladiator represented something completely different. The most famous martyr of the Roman Republic – Marcus Tullius Cicero – used the physique of gladiators to not have a good time the Republic's brave heroes, but to mock their bloated muscles because the embodiment of amoral tyranny.

Enemies of the Republic?

Cicero's profession was each shaped and shaped by The constitutional crises this shaped the last a long time of the Roman Republic. In several of his speeches from this era he referred to the enemies of the republic as gladiators.

In the so-called second Catilinarian conspiracy from 62 B.C. BC, Lucius Sergius Catiline, also often known as Catilineattempted a coup after losing his election campaign Become consul. Rome's highest office, a consul, was roughly similar to that of a U.S. president, except that he served alongside one other consul for a 12 months, each wielding equal political power.

Stockmontage/Getty Images

Cicero, who was consul himself that 12 months, made no compromises in his speeches. They were all based on the concept the would-be usurper Catiline – although of noble birth – was an enemy because he related to “the criminals of the gladiatorial schools.”

The true defenders of Roman values – not less than in response to Cicero – exchanged harsh words within the Roman Senate. Catiline, then again, “trained” his superhuman physical strength to inflict “insult” and “malice” on the Republic, its institutions and its freedoms, all with a dagger, the weapon of gangsters and cutthroats.

Just a few a long time later, when the Roman Republic gained unprecedented political power within the hands of three menCicero again used the figure of the gladiator as a disturbing symbol.

This time he used it to summon one among these three “Triumvirs”. Mark Anthonywhose later alliance and affair with Cleopatra made him an enemy not only of the Roman Republic but additionally of Roman identity itself.

In his glowing second Philippians – one among 14 insults against Antony – Cicero spotlighted Antony's robust gladiator body and monstrous capability for self-indulgence. This was a disgrace unworthy of the Roman population and contradicted the normal value of self-restraint in Roman political life:

“You! With your neck, your sides, your hard gladiator body: you drank so much wine at Hippia's wedding that the next day you had to vomit everything in front of the Roman people.”

But beyond the easy proven fact that most gladiators were enslaved – and for that reason despised by the elites social outsiders – There is another excuse for the spread of this image in Roman political language.

Caricature as a personality

To take part in Rome's political culture, training in rhetoric and oratory was crucial.

Although much of oratorical training was acquired by following one's teachers, in the primary century B.C.E. BC led to an influx of influential rhetoric teachers from Greece and an increase in what could loosely be described as rhetoric textbooks. These handbooks not only offer theoretical discussions about what makes a superb speech, but additionally reveal rather a lot about Roman values.

Books just like the anonymous “Rhetoric for Herennius“, which circulated within the early years of Cicero's political profession, was filled with examples of the characterization of the opposition in court.

The writer – as Cicero wrote in his own work: “About rhetorical brianstorming” – emphasized that discussions about physical characteristics usually are not just fair game; It was almost expected that they might highlight the virtuous – or vicious – character of a plaintiff or defendant.

For example, beauty could possibly be used positively to point out how nature's blessings increased a client's virtue without resulting in pride. If the characterization is unfavorable, the identical beauty could possibly be interpreted as a product of the opponent's vanity and self-indulgence.

More on the tip of the sword: According to the writer of “Rhetoric for Herennius,” qualities corresponding to speed and strength could possibly be emphasized to point out “respectable training and effort” when done carefully. However, when you're attempting to tear down an opponent, the speaker can “mention his effort.” [speed and strength]which each and every gladiator can have due to silly luck.”

Strength? Definitely.

Honor? Depends on who you ask.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply