Home insurance prices are rising across the United States, not only Florida suffered losses within the tens of billions from Hurricanes Helene and Milton, but across the country.

According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, home insurance increased by a mean of 11.3% nationwide in 2023, with some states, including Texas, Arizona and Utah, seeing increases nearly double that. Some analysts predict one average increase of about 6% in 2024.

These increases are because of a potent mixture of rising insurance payments and rising construction costs as people in danger construct increasingly expensive homes and other assets.

If home insurance costs a mean of $2,377 per 12 months nationwide, and $11,000 per 12 months in Floridathis can be a blow for many individuals. Despite these rising rates of interest, believes Jacques de Vaucleroy, CEO of reinsurance giant Swiss Re US insurance prices are still too low to completely cover the risks.

It's not only the premiums which might be changing. Meanwhile, insurers often reduce coverage amounts, limit payouts, increase deductibles and impose recent conditions and even exclusions for some common perils, resembling protection against wind, hail or water damage. Some require certain preventative measures or use risk-based pricing – charging higher fees for homes in flood zones, areas liable to wildfires, or in coastal areas liable to hurricanes.

Homeowners concentrate to their prices rise faster than inflation might think something sinister is at play. Insurance corporations face the challenge rapidly evolving risksHowever, they try to maintain the costs on their policies low enough to stay competitive, but high enough to cover future payouts and remain solvent in a stormier climate. This is just not a simple task. In 2021 and 2022, seven property insurers filed for bankruptcy in Florida alone. In 2023 Insurers lost money on homeowners insurance in 18 states.

But these changes are raising alarm bells. Some industry insiders worry that insurance could lose its relevance and its real or perceived value to policyholders as coverage shrinks, premiums rise and exclusions increase.

How insurers assess risk

Insurance corporations use complex models to estimate the probability of current risks occurring based on past events. They aggregate historical data – resembling event frequency, magnitude, losses and contributing aspects – to calculate price and coverage.

However, the rise in disasters makes the past an unreliable benchmark. What was once considered a 100-year event may now be higher understood as a 100-year event 30 or 50 12 months event in some places.

What many individuals don't realize is that the rise of so-called “secondary hazards“—an insurance industry term for floods, hailstorms, high winds, lightning strikes, tornadoes, and wildfires that cause small to medium-sized losses—is becoming the first reason for the insurability challenge, especially as these events develop into more intense, frequent, and cumulative, which reduces insurers' profitability over time.

Jon Cherry/Getty Images

Climate change plays a task in these increasing risks. As the climate warms, the air can hold more moisture – about 7% more with every degree Celsius of warming. This results in heavier rainfall, more thunderstorms, larger hail events and in some regions a better risk of flooding. The USA was average 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.6 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer in 2022 than in 1970.

Insurance corporations are revamping their models to maintain up with these changes, just like when smoking-related illnesses became a major cost burden in life and medical health insurance. Some corporations use climate modeling to reinforce their standard actuarial risk modeling. But some states were hesitate to permit climate modelingwhich may result in corporations systematically underrepresenting the risks they face.

Each company develops its own assessment and geographical strategy to achieve a distinct result. For example, Advanced insurance increased its home ownership tax rates by 55% between 2018 and 2023, while State Farm only increased them by 13.7%.

While a home-owner who chooses to make home improvements, resembling adding a luxury kitchen, may face a rise in premiums to reflect the extra alternative value, this effect is often small and predictable. In general, the larger premium increases are because of the ever-increasing risk of storms and natural disasters.

Insurance for insurers

When risks develop into too unpredictable or volatile, insurers can turn to reinsurance for help.

Reinsurance corporations are essentially insurance firms that insure insurance firms. But lately, reinsurers have recognized that their risk models are not any longer correct and have done so increased their tariffs accordingly. Property reinsurance alone increased by 35% in 2023.

Reinsurance can be not very suitable for covering secondary risks. The traditional reinsurance model focuses on large, rare catastrophes resembling devastating hurricanes and earthquakes.

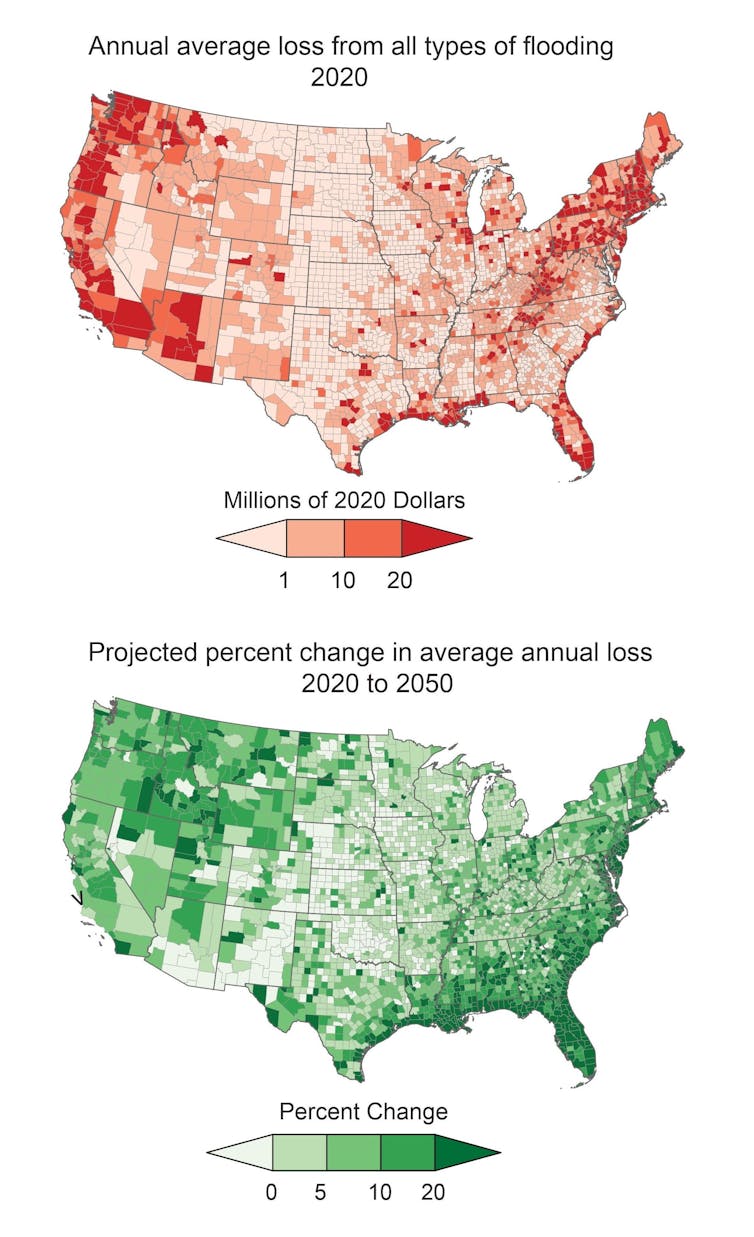

Fifth National Climate Assessment

As another, some insurers are doing this parametric insurancewhich provides a predefined payment when an event reaches or exceeds a predefined intensity threshold. These policies are less expensive for consumers because payouts are capped and canopy events resembling a magnitude 7 earthquake, excessive rain inside 24 hours, or a Category 3 hurricane in an outlined geographic area. The caps allow insurers to supply a less expensive type of insurance that’s less prone to impact their funds.

Protection of the buyer

Of course, insurers don’t operate in a totally free market. State insurance regulators evaluate and approve or reject insurance firms' proposals to extend rates.

The insurance industry in North Carolina, for instance, where Hurricane Helene caused catastrophic damage, is advocating for one Increase in home ownership premium by a mean of greater than 42%starting from 4% in parts of the mountains to 99% in some coastal areas.

If a rate increase is rejected, it could force an insurer to easily withdraw from certain market sectors, cancel existing policies, or refuse to put in writing recent policies if their “Loss rate“ – the ratio of claims paid to premiums collected – becomes too high for too long.

Since 2022, seven of the highest 12 insurance carriers have either cut existing homeowner policies or stopped selling recent ones within the wildfire-prone California homeowner market, and an equal number have pulled out of the Florida market because of rising hurricane costs.

California desires to stop this flood reform its regulations to hurry up the approval process for rate increases and permit insurers to make their case using climate models to more accurately assess wildfire risk.

Florida has implemented regulatory reforms which have reduced litigation and associated costs and has eliminated 400,000 policies from the state's insurance program. As a result, Eight insurance carriers have entered the market there since 2022.

Looking ahead

Solutions to the growing insurance crisis also include how and where people construct. Building codes may require more resilient homes, just like how fire safety standards increased the effectiveness of insurance many a long time ago.

One estimate suggests $3.5 billion could possibly be invested to make the two-thirds of U.S. homes which might be currently out of code more resilient to storms Save insurers as much as $37 billion until 2030.

If the affordability and relevance of insurance continues to deteriorate, property prices in exposed locations will ultimately fall. This shall be essentially the most tangible sign that climate change is triggering an insurability crisis that affects overall financial stability.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply